Inabeze Medikintos felt sure she was about to die. A mob had seized her, and she was now separated from her colleagues in the Burundian police force. "Leave her for us!" an angry civilian shouted at the backs of Medikintos's retreating colleagues.

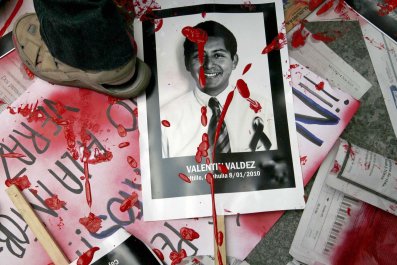

Medikintos screamed as her attackers hurled rocks and blunt objects at her head and jostled to stab her with a kitchen knife. Police had just opened fire on protesters on May 13 in the country's capital city, Bujumbura, in a bid to disperse them, killing one. But the protesters, who were angry at the government, had picked up sticks and stones and were using them in pitched battles. The police had turned and fled. The group surrounding Medikintos accused her of shooting a female protester. "They could have killed me," recalls Medikintos, a former fighter in the rebel group that brought the country's president to power. She escaped after a civilian calmed the mob down.

Now the skirmishes between forces loyal to the president and his opponents flare almost every day. Opposition supporters have mounted attacks on police, sometimes with grenades, and in mid-December they staged coordinated attacks on army bases in the capital. In retaliation, police hit squads executed dozens of civilians, residents of affected neighborhoods say. At least 400 people have died in the violence, and more than 220,000 people have fled to neighboring countries.

On December 17, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, Zeid Ra'ad al-Hussein, said Burundi was on the "very cusp" of civil war. That same day, the African Union met and, in a statement on social media, vowed that Africa would not "allow another genocide to take place on its soil." The AU's peace and security council has proposed the deployment of a peacekeeping force in Burundi to protect civilians and prevent further deterioration in the security situation.

The violence began in April after President Pierre Nkurunziza declared his intention to run for a third term, which opponents say is illegal. Western powers fear the unrest could destabilize the Great Lakes region of Africa, where memories of the 1994 genocide in neighboring Rwanda are still fresh. Fourteen percent of Burundi's population is from the Tutsi ethnic group, and 85 percent is from another ethnic group, the Hutu. The Tutsis traditionally held power in Burundi, until 1994 when Cyprien Ntaryamira, a Hutu, was elected president. Ntaryamira was killed alongside the Rwandan president, Juvénal Habyarimana, when their plane was shot down later that year. The killings sparked the genocide in Rwanda and led to a civil war in Burundi that claimed the lives of 300,000 people.

For now, the divisions are political rather than ethnic. But historical enmities could flare again, particularly if the rumored involvement of the pro-Hutu rebel group, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, prove to be true. The group was founded by members of the Hutu Interahamwe militia that organized the killing of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in Rwanda in 1994.

Human rights groups, including Amnesty International, have collected evidence of increasing abuses perpetrated by state security forces. The Burundi government disputes that and says the opposition is carrying out the attacks on civilians. "The government cannot kill its people," says presidential spokesman Willy Nyamitwe. The opposition, he says, "have been killing people and throwing bodies in the streets because they wanted to catch the attention of the international community."

As the two sides intensify their rhetoric and the violence worsens, most people in Burundi hope for one thing above all others: that their country doesn't slide back into war and become the site of another mass slaughter.