"They attacked my home but stole nothing," says Anabel Hernández, describing a break-in at her Mexico City home in November. "There was money lying on the table, but they didn't take a cent. They were after my files. It was an act of intimidation."

Hernández, author of the best-selling book Narcoland, is one of Mexico's most prominent investigative journalists. The recent intrusion is just the latest in a long line of death threats and assaults she has faced for her work exposing the links between Mexico's drug cartels and corrupt government officials.

Hernández is now pursuing two major investigations: the disappearance in August 2014 of 43 students from Ayotzinapa in the southern state of Guerrero and the escape this past July of Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán, one of Mexico's most powerful drug lords, from a maximum-security prison. "They're investigations that have made the government very uncomfortable," she says. And they have also made her a target yet again.

The break-in at Hernández's home in November was one of several assaults on high-profile Mexican journalists that month. On November 20, someone raided the apartment of Gloria Muñoz Ramírez, director of the news website Desinformémonos. It happened a week after hackers attacked the Desinformémonos server.

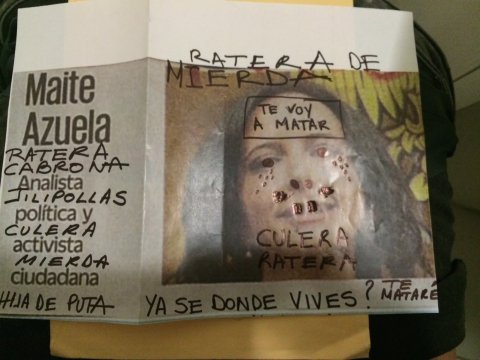

A few days later, Maite Azuela, a columnist for El Universal, one of Mexico's most prominent newspapers, received a letter in the mail. It contained a picture of Azuela with her eyes blacked out and a chilling message scrawled below: "I know where you live, and I'm going to kill you."

Journalists have long faced violence and intimidation in Mexico from cartels on one side and corrupt authorities on the other. But according to Article 19, an international human rights group defending freedom of expression, there has been a sharp rise in attacks in recent years.

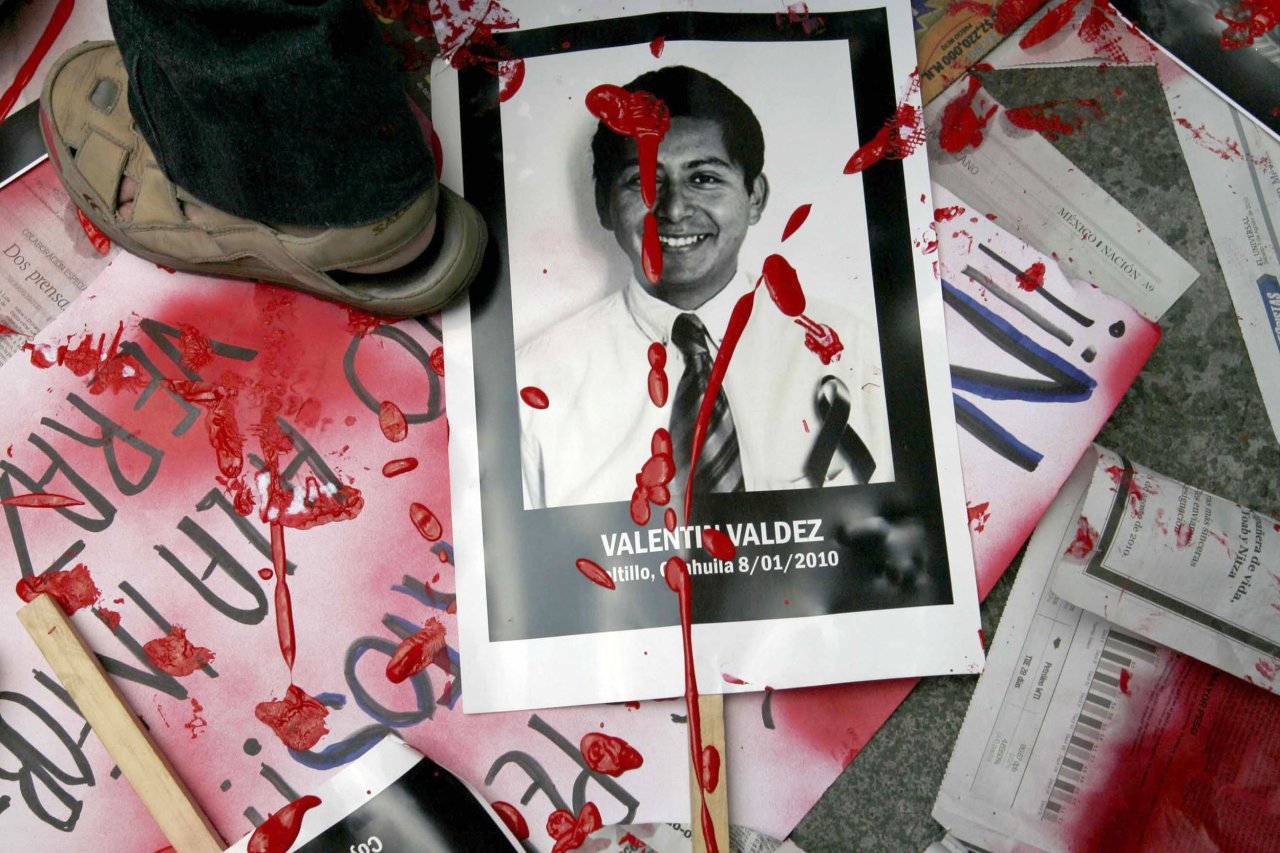

During the presidency of Felipe Calderón, from 2006 to 2012, there was an average of one incident against journalists every two days. Under current President Enrique Peña Nieto, that's gone up to one every 22 hours. Since 2000, 16 journalists in the country have been reported missing and 88 have been killed—seven have been murdered in 2015 alone. According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Mexico is the most dangerous place to be a journalist in the Americas, with about a third of the documented murders of journalists since 2010 having occurred in the country.

"It's a national emergency," says Darío Ramírez, from Article 19 in Mexico. "There are black holes of information across the country where no one knows what's going on."

For Hernández and many others, what angers them most is the impunity. Despite the dozens of murders and attacks on journalists, there have been few arrests and fewer convictions: "The penal system is abysmal," says Carlos Lauría from the Committee to Protect Journalists. "There's no sense of punishment."

There have been token measures taken. In 2012, Peña Nieto's administration created the Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, which last year determined that Hernández's situation was of "extraordinary risk." But without a commitment to investigate and prosecute offenders, Hernández says such authorities are completely ineffective. "There's been no investigation of the assault on my home," she says. "This kind of impunity demonstrates that these institutions just aren't working."

There was an international outcry when photojournalist Rubén Espinosa was assassinated in Mexico City in July. The incident sent shockwaves across the country because while attacks against reporters have become common in many states wracked by the country's long-running drug war, the brutal killing of a well-known journalist in the nation's capital was unheard of. "I cried for three weeks," says reporter Thalía Güido. "We all thought Mexico City was a bubble, but when Rubén was killed, everything was broken. We realized the bubble isn't untouchable, and they'll break it whenever they want."

At 26, Güido is just starting her career, but she understands all too well the danger she faces. "I've had my email account hacked. I know I'm being watched," she says. "Not because of who I am but because of who I've worked with." Guïdo was mentored by Marcela Turati, another highly respected investigative journalist, who created Periodistas de a Pie, or Journalists on Foot, an organization that aims to improve the quality of Mexican journalism through training and collaboration.

Turati too has received death threats, but she says Espinosa's murder still came as a huge shock: "He gave TV interviews weeks before he was killed saying he felt threatened. He sought protection from human rights groups and government agencies. And he worked for national media companies. But his death showed us all that nothing works—not visibility, not major outlets, not the government. Nothing can keep you safe."

Following mass protests in Mexico City over Espinosa's murder, President Peña Nieto was forced to speak out. He said at a press conference, "Attorneys and prosecutors are committed to redouble their efforts and provide timely attention to the investigation and arrest of those responsible for assaults, killings and attacks against journalists."

Despite such promises, even the high-profile case of Espinosa was marred by well-documented mismanagement and obfuscation of evidence by the city's justice department. "We're in the same dark lagoon as we were the day this happened," says Turati.

Espinosa worked in the Mexican state of Veracruz and was a well-known critic of its governor, Javier Duarte. Veracruz under Duarte has become the most lethal place in the country to practice journalism: Espinosa was the 14th journalist who reported from Veracruz to be killed under Duarte's tenure.

"The state is a poisonous broth," says Jorge Morales, who works at the Veracruz Commission for Attention and Protection of Journalists. Prior to joining the commission, Morales was a journalist for 15 years and experienced intimidation and violence numerous times. He also worked with Espinosa and many other journalists killed in the state. "Everything here is being held together by pins," he says. "The government is trying to suffocate us."

Veracruz is not the only state with a problem. According to Article 19, about 80 percent of attacks against journalists occur outside of Mexico City. Tamaulipas, Michoacán, Guerrero and Oaxaca have all seen a sharp increase in attacks against journalists in the last 12 months. Many of these states are embroiled in drug violence. But even calmer states aren't immune: Quintana Roo, home of tourist hot spots like Cancún and the Riviera Maya, has seen the second-highest rate of attacks against journalists in the country.

Lydia Cacho is another of Mexico's most recognized and influential investigative journalists. She has long reported on violence and sexual abuse against women and children. Since 1986, she's lived in Cancún—except when death threats have forced her to flee the country.

Cacho's most recent investigation for Newsweek en Español, "Tulum, Land of Ambition," in September, exposed an ongoing war between corrupt politicians and ambitious businessmen, with local landowners caught in the middle. After the article was published, Cacho began receiving a new round of death threats. Then came the online attacks.

While reporter Javier Solórzano was interviewing Cacho on September 8, the website where the exchange was being live-streamed was hacked and shut down. This too, says Cacho, is becoming increasingly common. "They're finding ever more sophisticated ways to attack and humiliate you online," she says. "After the death threats, the paid ads on Facebook against me, the murders across the state, my security advisers told me not to be in Quintana Roo."

Cacho says the stress and trauma of the job under such conditions is often underestimated. "Most of my friends who have been killed doing this job were so emotionally exhausted," says Cacho. "They started to get careless, using apps and online tools that were easily traceable. 'They're going to find me anyway,' they'd say."

Not all assaults against journalists come in the form of violence or online attacks—often they're blackmail or bribes, known colloquially as chayote. Cacho says she's been offered numerous bribes, including $3,000 recently to write a favorable column about a politician she declined to name. When she refused, the briber listed a number of other journalists who had accepted the "donation."

"It's the same old techniques of silver and lead," says John Ackerman, an author and professor at the Institute of Legal Research of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. "They buy loyalties on the one hand, and fire, intimidate and murder on the other."

As a result, there's a fundamental mistrust of the media from the population at large, particularly of mainstream outlets. "People see the press as sold out," says Turati. "They see it as their enemy."

The consequence, says Ackerman, is "an authoritarian state where public discussion and debate are shut down. Mexico is no longer a democracy."

This, for many, is the crux of the problem. "These attacks against journalists are above all attacks against the fundamental human right of freedom of expression," says Hernández, the investigative journalist. "The ultimate victim is a society that no longer has access to the truth."