This article first appeared on The Trace, an independent, nonprofit media organization dedicated to expanding coverage of guns in the United States.

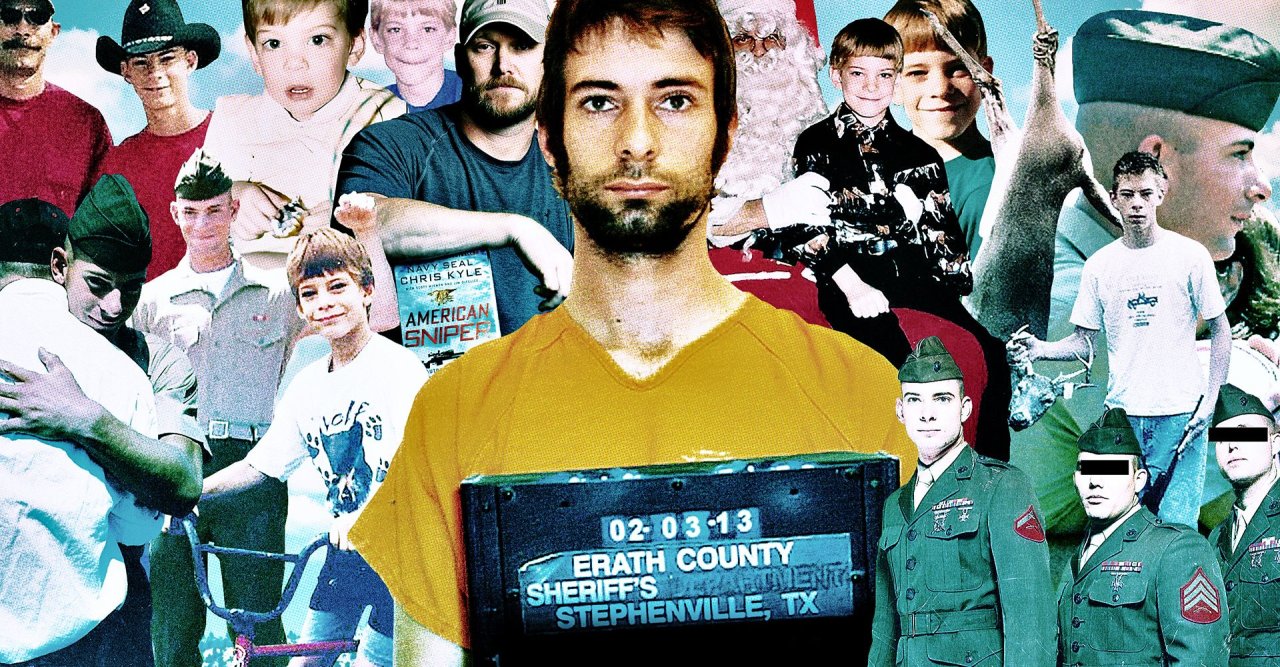

For months, Jodi Routh would come home from work afraid she'd stumble upon the dead body of her son. A 25-year-old former Marine, Eddie Routh had moved back to her home in Lancaster, Texas, a small, middle-class suburb just south of Dallas. It was early 2013, and he'd recently taken a job at a local cabinet shop but was struggling with what doctors said was post-traumatic stress disorder. His anxiety was so severe he couldn't drive on his own, and he believed his colleagues were cannibals who planned to eat him.

Jodi would drop off her son in the morning on her way to work, and the shop's owner would bring him home. Because Jodi worked later, Routh was alone for a few hours each afternoon. "When I'd start back to the house," Jodi recalls, "I'd be like, Please don't let me find him dead. I was so afraid he was going to kill himself. Because that's what he wanted." Late at night, he would often climb into bed with her. "This was a 6-foot-2 Marine," she says. "A tough man calling for his mama."

Routh had become concerned about the state of his soul, and when he and his mother arrived at the cabinet shop on the morning of February 1, 2013, he asked if they could pray together. In the parking lot, Jodi held her son's hand. Wiry since boyhood, he had a narrow face and a beak nose, with nervous eyes and an unkempt beard. Before he left the car, he asked the Lord to watch over his mom and dad.

Jodi was headed out of town that afternoon to spend the weekend with her husband, Raymond. She took comfort in knowing that Routh's girlfriend would be staying at the house and that his uncle would check on him.

But Routh had plans for an excursion his mother didn't know about. The following day, on February 2, Chris Kyle, the most prolific sniper in American military history, arrived with a friend, Chad Littlefield, to take Routh to a shooting range. Jodi's concerns, it turned out, had been misplaced. Her son did not commit suicide. He did something much worse: He killed the two men.

'You Killed a Texas Hero'

Kyle's death generated an outpouring of grief in Texas, where thousands piled into Texas Stadium, the home of the Dallas Cowboys, for his memorial service. It also resonated with gun enthusiasts across the country, who had embraced Kyle as a modern Wyatt Earp. His legacy was enhanced by his books, especially American Sniper , which chronicled his exploits as a Navy Seal in Iraq, where he logged 160 kills, a U.S. military record.

The film adaptation of his story, starring Bradley Cooper, was already in theaters in Stephenville when Routh's murder trial began there on February 11, 2014. Outside the courthouse, local vendors sold Chris Kyle baseball caps. A week earlier, Governor Greg Abbott declared February 2, the anniversary of the murders, Chris Kyle Day.

Routh pleaded innocent by reason of insanity, though the medical expert hired by the defense, a forensic psychiatrist, disagreed with the PTSD diagnosis the Marine had received at the Dallas Veterans Affairs hospital. The expert believed Routh was schizophrenic and suggested he suffered from paranoid delusions. In a videotaped confession to a Texas Ranger after the killings, Routh said, in reference to Kyle, "I knew if I did not take his soul, he was going to take mine."

The prosecution, however, said Routh was a psychopath who had calculated his odd statements to keep himself out of jail. After deliberating for less than two hours, the jury agreed, and he was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Related: 'American Sniper' and the Soul of War

Many applauded the verdict. Marcus Luttrell, the former Navy SEAL whose autobiography was the basis for the film Lone Survivor, tweeted, "Justice served for Chris and the Littlefield family." To Routh, he continued: Just wait until the correctional officers "find out you killed a Texas hero."

But the truth about Routh is far more complicated. Recently, Jodi and Raymond shared hundreds of pages of confidential medical records with me. The documents, which went largely unused during the trial, show that in the two years leading up to Kyle's murder, Routh suffered a series of psychotic breaks and may have been misdiagnosed. "The VA should have been more careful," says Dr. Amam Saleh, a forensic psychiatrist who reviewed Routh's medical records at my request. "Something was missed."

The Land of Corpses

Across the country, thousands of Americans have come home scarred by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In September 2007, Routh was deployed to a forward operating base about 60 miles north of Baghdad, where he repaired weapons and worked as prison guard for six months. It was his only war-related experience, though in January 2010 the Marines sent him to Haiti on a humanitarian mission, after an earthquake devastated the country. He told his parents he was responsible for clearing the land of corpses, including dead babies. There is no documented evidence to confirm Routh's account, but when he returned to the U.S., Jodi recalls, "he was just so messed up."

In late July 2011, a little more than a year after he received an honorable discharge from the military, Routh appeared at the Dallas VA, complaining that a tapeworm (which did not exist) was eating away at his insides. This is when the VA first diagnosed him as having PTSD, according to his medical records. Doctors prescribed him risperidone, an antipsychotic, as well as other medications to treat depression.

Several days later, Routh threatened to kill himself with the .357 Magnum his father kept in his car. Again, his family took him to the Dallas VA, where he remained for nearly two weeks. The clinical notes from August 3 say Routh was "psychotic." At one point, he told the staff, "You are all in this game. I can see the smoke in the mirror. We are all actors."

Over the next year, through 2012, Routh's symptoms worsened. He was convinced the government was spying on him, and he reported having auditory hallucinations, like hearing music that appeared to be "picked up [from] a radio station." He again threatened to kill himself, which prompted his parents to remove all of their guns from the house. Routh blamed the incident on booze. Records from around this time note that the VA offered him inpatient treatment for alcohol abuse, which the clinicians seemed to think was the trigger for his psychotic episodes. Routh declined. He also stopped taking his medication, saying that the drugs made him feel like a "fucking zombie."

In early January 2013, Jodi met Chris Kyle, who'd been out of the military since 2009 and took a keen interest in working with veterans suffering from PTSD. He had his own difficulties with life after the war and, like many former soldiers, saw therapeutic value in exercise and going to the shooting range.

Kyle's children attended the school where Jodi worked as a teacher's aide. She had heard about Kyle's work with veterans, and one day she approached him in the parking lot and asked if he might be able to help her son. Kyle was sympathetic. He took Routh's phone number and promised to call. Less than two weeks later, Jodi bumped into Kyle again. He said he was planning to take Routh shooting soon.

"At that moment, I thought it was fine," Jodi says.

It's understandable why she reached this conclusion. Each time the VA released Routh, his doctors said he didn't pose a threat to himself or others. But on January 19, shortly after Jodi saw Kyle, Routh suffered his most severe psychotic break yet. When it happened, he was at the apartment of his new girlfriend, Jennifer Weed. Brandishing a knife , he barricaded the front door, holding Weed and her roommate hostage. According to his medical records, Routh believed he was protecting them from the "evils of the world." The roommate called the police, who took Routh to Green Oaks Hospital in Dallas.

The doctors there believed Routh was suicidal and homicidal. He cried intermittently and made a series of strange statements. "I've been losing my fucking mind," he said. "Your mind is the only one you've got, you know?" At one point, he asked a doctor, "You got any idea how long they been recording this? You know—this Mickey Mouse bullshit going on all across America?"

After Routh cornered a female technician, a doctor noted that in addition to suffering from PTSD, the former Marine appeared to be in the throes of "first-break schizophrenia." He said Routh was "paranoid and impulsively violent" and that he needed to be hospitalized in a psychiatric ward for five to 10 days. The doctors gave him several medications, including Haldol, Paxil and Seroquel.

On January 21, he was transferred to the care of the Dallas VA. Just three days after Routh arrived there, the VA prepared to discharge him, even though it had received the clinical notes from Green Oaks. Jodi believed he was not ready—he still had crying spells and seemed unstable. She requested her son remain at the facility until he could be admitted to a residential treatment program for PTSD in Waco. But a social worker denied her request, saying Routh would have to go through the application process like everyone else. Jodi then begged to no avail. "I advised her that [Routh] will be discharged tomorrow," the social worker explained, as noted in the medical records, "as his paranoia symptoms are no longer present, he is not S/I [suicidal] and not H/I [homicidal]."

Unlike Green Oaks, the VA never considered that Routh might have schizophrenia, an illness that generally surfaces in early adulthood. The disorder is marked by the sort of delusions and paranoia Routh had experienced. Left untreated, it can lead to violent behavior, which is only compounded by alcohol. Saleh, the forensic psychiatrist, says large facilities like VA centers often treat patients based on doctors' previous conclusions, which can blind them to other possible diagnoses.

Green Oaks had the benefit of examining Routh without preconceptions. The VA did not. A spokesman for the hospital says the knife episode was triggered by a "recent binge on alcohol and marijuana and being off his psychiatric medications"—issues the VA had previously blamed for Routh's psychotic behavior. Green Oaks's records, however, state that he was not intoxicated when he arrived at the facility. A psychotic break caused by substance abuse, not schizophrenia, may require a less aggressive medication regimen and a shorter period of hospitalization, according to Saleh.

Five days after his discharge, Routh exhibited no signs of hallucinations or delusions. It was an encouraging snapshot, but it captured Routh's state of mind only on that particular day. The doctor did increase the dosages of Routh's medications, but the new prescriptions, the records state, weren't sent out until "on or about" February 2, 2013, the day Routh went to the shooting range with Kyle.

'This Dude Is Straight-Up Nuts'

The night before he met Kyle, Routh proposed to Weed without a ring. The next morning, according to news reports, the two got into an argument and she left the house. Later, Routh's uncle, James Watson, stopped by to check on him. They smoked marijuana, and Routh drank whiskey.

That afternoon, Kyle and Littlefield pulled up to the house in the sniper's black Ford F-350. Routh hadn't told anyone they were coming to get him, and he hopped into the truck without saying goodbye to his uncle.

As Kyle steered them onto the highway, he could tell there was something off about Routh, who sat in the back of the truck. Kyle texted Littlefield, who rode beside him in the passenger seat.

"This dude is straight-up nuts," he wrote.

Littlefield replied, "He's right behind me, watch my six."

Around 3 p.m., the group pulled up at Rough Creek Lodge, a luxury resort 90 miles southwest of Lancaster. The property is 11,000 acres, with large tracts of land set aside for hunting and golf. The range, which Kyle helped design, is down a dirt road that extends for several miles. Before the three men mounted an elevated deck and began to shoot, they raised a red Bravo flag, signaling others to stay away.

Two hours later, an employee drove onto the range and discovered two bodies. Kyle was facedown in front of the deck. He had been shot six times with a .45-caliber pistol. Littlefield had been shot seven times with a 9 mm Sig Sauer handgun. It was engraved with the familiar Navy anchor insignia. Routh had used Kyle's weapons to kill them.

Mike Spies (@MikeSpiesNYC) is a staff writer at The Trace.

The Trace believes that this country's rates of firearm-related deaths and injuries are far too high. But The Trace is focused on a second, related problem. There is a relative shortage of information on the issue, a shortage caused in part by the gun lobby's efforts to squash gun-violence research and limit law-enforcement data. The company takes it as its mission to address that information deficit through daily reporting, investigations, analysis and commentary on the policy, politics, culture and business of guns in America.