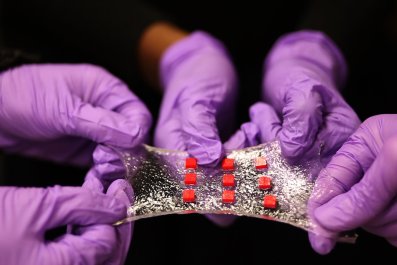

Earlier this month, I visited a relatively new restaurant in central San Francisco. It was a clean, bright place, busy on a wet Thursday afternoon. A friendly employee greeted me at the entrance, directing me to one of two touch-screen kiosks, each about the size of a door. It looked like one of those machines that spit out your boarding pass at the airport with somewhat disconcerting speed; this one, though, was going to take my lunch order.

I scrolled through photographs of appetizing hamburger and sandwich variations, settling on grilled chicken on a ciabatta bun. From a menu of toppings, I added tomato, guacamole and cheese. The employee who'd greeted me looked on, pleased. She suggested I take a seat while the sandwich was being prepared, so I found a space at a counter and opened my computer: The restaurant has wireless service. On the wall across from me was a mural with bacon slices, mushrooms and wheat stalks spelling out LOVE. I settled into my chair and waited contentedly as, outside, a winter rain poured down on a parched San Francisco.

The restaurant was a McDonald's: You know, golden arches, chicken nuggets, enough calories in a single Extra Value Meal to sate Slovenia. But what distinguishes this outpost from the vast majority of the world's 32,000 other McDonald's branches is that it is home to the chain's Create Your Taste program, which lets customers design their meals through digital kiosks. There is a "regular" McDonald's behind the Create Your Taste kiosks, but it's hidden away, sort of like the embarrassing older sibling, still living at home and playing video games, the one you don't want your visiting college friend to mingle with. Create Your Taste started in only about 30 restaurants late last year; the company's goal then was to install 2,000 such stations at McDonald's branches around the United States.

This was encouraging, but also disorienting. In my younger days, I used to love McDonald's because I knew that I could get the same french fries in Manhattan and Paris (and, yes, I have eaten McDonald's in Paris). The chain is a master peddler of grease and predictability, which is probably why it did so well when it opened its first branch in Moscow in 1990, catering both to a curiosity about the West and a Soviet worship of uniformity. So what was this business with choices? Had the iron-fisted Hamburglar mellowed out?

Here's a hint: Take a look at your local Chipotle at a lunch hour, the huddled masses yearning for their Barbacoa Burrito Bowls. McDonald's is fast food's past, while Chipotle is very much its present (though the latter's image hasn't been helped by recent outbreaks of foodborne illness). Chipotle has perfected the fast-casual approach, which stresses fresh ingredients, visibility of preparation and customer freedom to mix and match ingredients. It is an approach that has also worked for the bakery chain Panera, the salad chain Chopt and Shake Shack, the high-endish burger chain valued at $1.6 billion when it went public early this year. At these upstarts, you may pay a little more, but in return you eat real food in something that's close to a real restaurant. McDonald's, meanwhile, has had to contend with "pink slime" and the general perception that its food is about as healthful as deep-fried asbestos. An average Chipotle branch is worth $10.5 million, according to Business Insider, while the average McDonald's branch is worth only $2.9 million.

The rise of Chipotle and similar chains has traditional fast food outlets scrambling to retain customers, either by imitation or, as is increasingly common, inebriation. Anything to keep you from getting your next lunch from Lyfe Kitchen or Dig Inn. McDonald's is the biggest but hardly the only old guard fast-food establishment making a bid for an American public that, suddenly, cares about the food it eats. Dubiously touting the quality of its meats, Arby's is returning to Manhattan, where it is opening what the New York Post says will be the smallest restaurant in the chain, with "just 48 seats spread over just under 2,000 square feet," thus ensuring that nobody will mistake the place for a Soviet-era cafeteria in outer Bucharest. Panda Express is back in New York City too, using an #OrangeChickenLove campaign to appeal to millennials and people who can't seem to find authentic Chinese food in one of the city's three Chinatowns. There was even an Orange Chicken Love food truck, which toured the nation, dispensing the oleaginous nuggets that made Panda Express famous.

After a few minutes of waiting, I saw a server happily approaching. On the tray she bore sat my chicken sandwich, a plump ciabatta bun cradling a decent slab of what looked very much like breast meat that had come from a once-living bird of the Gallus gallus domesticus species. I bit into the sandwich with trepidation, but quickly found myself relieved: The chicken tasted like chicken. The bread was soft. The cheese was gooey, warm. Much like American democracy, the thing was a little sloppy and deeply imperfect, but on some basic level, it worked marvelously well.

Upgrading ingredients, as McDonald's is doing, is extremely expensive. It's much easier to get your customers drunk and hope they won't notice how bad the food is until the next morning. This fall, Burger King announced that it would start selling alcohol in its stores in Britain; a couple of years ago, a White Castle in Indiana became famous for pouring wine. The latter became a media sensation, with articles in Slate, The Wall Street Journal and elsewhere.

Maybe it's some weird millennial irony: We visited chains like Burger King as kids or teens, then shunned them as we grew into adulthood. Now, though, we are old enough to engage in that fuzzy feeling for the early 1990s, a time before nitrites and trans fats, when nobody outside Berkeley knew about organic food and you couldn't care less if your meat had been raised on a drug regimen worthy of Ivan Drago.

Or maybe it's our strange relationship with corporations: We loathe them even as we need them, want to applaud them for doing good even as we condemn their intrinsic heartlessness and greed. So when Dunkin' Donuts rolled out its own version of the much-lauded cronut—a pastry created by a French baker in lower Manhattan—the fascination was universal, with coverage in NPR and USA Today and many other respectable outlets that probably should have been covering more serious matters. But we love nothing like deep-fried frivolity. And so the shamelessly named Croissant Donut took its star turn. We applauded the effort, we laughed at the imitation, and we gave Dunkin' Donuts our attention, maybe our money and possibly even a little bit of respect.

I remember the last time I had eaten Taco Bell: the spring of 2000. I was pledging a college fraternity, and to demonstrate my fealty to the brotherhood, I was made to consume a dangerously large number of Taco Bell tacos in a dangerously short span of time. I managed to stuff the shells into my mouth, but this was a gastronomic traffic jam that had only one resolution. Luckily, we were on the sidewalk by the time I started hurling.

So why had I now come to the Taco Bell on Third Street in San Francisco, a decade and a half later? Not to revisit my collegiate glories, I assure you. Rather, here, on the ground floor of a charcoal-colored condominium building in the gentrifying SoMa district, was Taco Bell Cantina, the chain's nascent foray into the fast-casual market. The concept was gloriously simple: hooch. Cheap hooch, loaded with enough sugar that you were going to get your rocks off one way or another.

Alcohol is a rarity at both fast-food and fast-casual restaurants, because they cater mostly to people eating lunch, and people eating lunch generally do not drink alcohol, unless they are named Don Draper, in which case they are definitely not taking their dirty martinis at Burger King. Alas, I was not able to sample the divine ambrosia that is Twisted Mountain Dew Baja Blast Freeze at the Taco Bell Cantina in San Francisco, because that branch does not yet have its liquor license. But the one in Chicago does. Its beverage director appears to be a 14-year-old who blows rails of Pixy Stix.

Without alcohol, I was left to a most terrible fate: eating Taco Bell while sober.

The suburb of Millbrae is south of San Francisco, in the shadow of the city's airport. The town has a large Asian immigrant population, and the main strip beckons with offerings like Chicken Pho You and Shanghai Dumpling Shop. I wasn't here for dim sum, though; in Millbrae, Starbucks is conducting an experiment called Starbucks Evenings, where from the afternoon until closing time, the coffee shop also becomes a bar, serving beer and wine, as well as small plates of the sort you might find in a hip Brooklyn or Oakland boîte.

It is telling that even a chain associated with urban sophistication feels the need to keep up with newer, cooler rivals. It is an article of faith that many establishments have better burgers than McDonald's, but while Starbucks may be a higher-order chain, it is just as true that many establishments have better coffee than Starbucks, making it imperative that the company tend to its image, lest its profits start to falter.

Starbucks Evenings is a wine and snacks program now at 75 outlets nationwide, from Brooklyn to Seattle, where the wine bar concept started. Maybe if Starbucks can't earn its cool with Indonesian beans, it can reclaim it with Sonoma grapes and spiced marcona almonds.

But as I very quickly discovered, there is something inherently weird about drinking wine in a coffee shop where middle-schoolers in hoodies huddle conspiratorially around iPhones, slurping pumpkin-flavored drinks. That was kind of a buzzkill. Still, a buzz was to be had: The Starbucks alcoholic offerings are arrayed tastefully on a shelf behind the bar, hovering above the coffee-making equipment. The barista was slightly surprised by my order—as I said, it was kind of early. But when I described my preference for earthy wines, she quickly recommended a cabernet. I sat at a communal table that featured magnetic wireless chargers that didn't quite work but were fun to play with.

A barista brought my wine in a stemless glass, along with a couple of snacking dishes: bacon-wrapped dates and truffle popcorn. Bacon is pretty much impossible to get wrong; Starbucks easily avoided that ignominious distinction with its umami morsels. The popcorn, though, was parched and flavorless. As for the wine, it was fine, far superior to the Yellow Tail you might find at a downscale bar, but nothing I wanted to truly savor or learn more about.

Starbucks has very little to lose: People don't drink coffee in the late evening, unless they are writers or psychopaths, so if it can keep its stores open by offering wine, it may well attract a new clientele. And if it wants to ever reintroduce social-good initiatives like #RaceTogether, the wine bar might be the place: I am going to need to be plenty drunk to discuss the coming Trump presidency.

The McDonald's artisanal sandwich, the Taco Bell margarita, the Starbucks pinot noir: These are all variations on Marcel Proust's madeleine, summoning a past that is very much ours but also, because it is past, no longer ours. It is all gone, the McNuggets after Little League games, the first surreptitious taste of your mother's cappuccino. Who, today, can eat a gordita without guilt? Who can drink a pumpkin spice latte without fear?

In the end, it's more than just playing catch-up to Chipotle. Chains like Taco Bell and Starbucks are banking on our shared cultural nostalgia and, at the same time, our current worship of innovation. "Some people like it," a worker at the San Francisco McDonald's told me, speaking of the new digital kiosks. "But they like the old way too."