Updated | On September 11, 2001, shortly after the second hijacked plane hit the World Trade Center, a woman fleeing the building discovered a hastily written note someone had dropped: "84th floor, West Office," it read, "12 people trapped." She handed the note to the nearest person in uniform—a security guard at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He hurried to alert first responders, but a few minutes later, the building collapsed. Among the nearly 3,000 people who died that day was Randolph Scott, a trader at Euro Brokers Inc. and the author of that note.

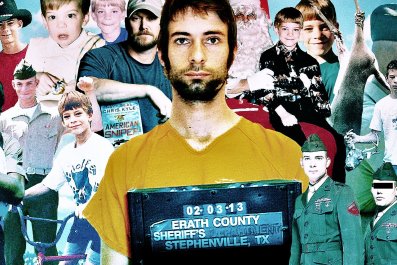

Fourteen years later, his daughters, Jessica and Rebecca, arrived at the U.S. military base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. They, along with six other family members of 9/11 victims, came here to witness pretrial hearings for alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) and his four alleged co-conspirators. A military commission is expected to eventually put the five on trial. But for years, the defense has filed motions, delaying the inevitable, as the two sides argued over the detainees' right to wear military attire in court and the microphones the FBI hid in legal meeting rooms, among other things.

On December 7, the presiding military judge, Colonel James Pohl, held a closed session to discuss classified evidence with the prosecution and defense. But the following morning, the families of victims, along with a limited group of spectators, made their way through the various check-ins and metal detectors before arriving at a small observation room in the back of the rectangular court. They took their seats, standing behind soundproof glass—the only barrier between them and the men who allegedly murdered their loved ones. As the tech-crew tested the microphones, the families watched as the hearing began. The audio, however, streamed into the room on a 40-second delay: If anyone in court slips and reveals classified information, U.S. officials can bleep it out, like swear words on an episode of Bad Girls Club. Experiencing this severe mismatch of audio and visuals is surreal—like watching a poorly synched movie, except this one lasts for days.

In the front of the courtroom, opposite the 9/11 families, the judge spoke to the defendants, who lined the far left wall. Most wore camouflage-patterned clothing and keffiyehs. KSM, sporting a long red beard, sat closest to the judge, then Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al Shibh and Ammar al Baluchi. The fifth defendant, Mustafa Ahmad al Hawsawi, placed an extra pillow on his chair, his lawyers say, as a result of rectal abuse he sustained while in CIA custody. (A CIA spokesman declined to comment due to pending litigation involving Hawsawi.) As the hearing continued, the defendants fumbled through documents and scanned their court-issued laptops. Their interpreters and lawyers sat beside them, helping them translate and understand the proceedings.

Later, during a recess, KSM and the other detainees placed small prayer rugs on the courtroom floor and bowed toward Mecca. Many in the small, tense gallery press against the glass to get a closer look. "I wanted to see the bastards, up front and in person," Alfred Bucca says. His brother Ronald—the first fire marshal to be killed in the line of duty in the history of the New York City Fire Department—died trying to save people trapped in the south tower before it collapsed.

When the break ended, Bucca and the others listened to the detainees' objection to being handled by female guards. "I don't get warm and fuzzy," says John Eric Olson, a 9/11 widower, about all the time and resources spent dealing with the complaints of the detainees. But he isn't frustrated with the slow-moving process. "These guys, as horrible as they are, are entitled to a zealous defense," he says. "And from everything I've seen [here], they're getting it."

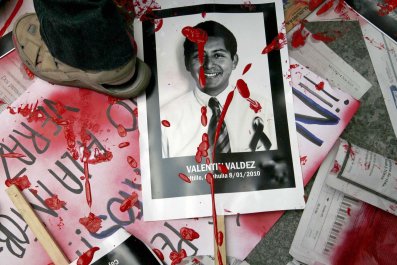

Phyllis Rodriguez, who lost her son Gregory in the World Trade Center attacks, agrees. "If we forgo some of the rights of these guys in order to have a speedy trial and a speedy resolution, whatever the verdict is, then who is next?" She was appalled by what she learned from the summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee's report on the CIA's secret rendition program. Released a year ago, it publicly confirmed that the agency used harsh interrogation techniques such as waterboarding and rectal rehydration on prisoners. "[Torture] is traumatic," says Rodriguez. "How many years will it take me to get over the death of my son? Would I be driven to say or do something based on the trauma of that? I am very rational at the moment, but I wasn't always so rational.

"It's very emotional," Rodriguez says of the hearings. "Every once in awhile I think, Wait a minute, how did this happen? Why am I coming here? And then I remember Greg. And that's why."

'I Had to Relive the Entire Thing'

In December 2008, the Office of Military Commission created a lottery for victims' families to attend the court sessions. For every round of hearings, the commission randomly chooses five people, who are each allowed to bring a supporter. Defense Department spokesman Commander Gary Ross estimates that 400 victims' relatives have signed up. Nearly 100 have attended so far.

"It is such a privilege to witness this process as an American citizen," says Julia Rodriguez, Phyllis's daughter. "I wish more people could see it." Her mother agrees, adding that the hearings should be more accessible to the American public—either by broadcasting them on television or moving them to federal courts. Bucca, however, would like the detainees to stay on the island. "Keep it open," he says of Gitmo. "Keep [the prisoners] far away."

The 9/11 families' politics vary. But what they share is the uniquely painful experience of witnessing the men accused of killing their relatives standing in front of them in court. Many are determined to follow the hearings and the trial, which may be years away. Among those who may return if permitted: Rebecca Scott, Randolph's daughter. In July 2011, Randolph's note wound up at the New York medical examiner's office. After testing it, the examiner identified the blood on the paper's edge and called Randolph's wife in to confirm the handwriting. "Instantly we were like [that's] dad's," his daughter says. "I had to relive the entire thing."

Whether watching the hearing at Gitmo or back at home, the 9/11 families are still living with their loss to this day. "I don't believe in closure," says Phyllis Rodriguez. "There's no such thing."

Updated to clarify how Randolph's family learned about the existence of his note.