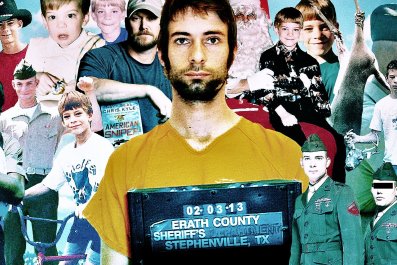

This probably isn't the Vermont you know, the quaint or hip parts with artisanal maple candies and transplanted New Yorkers in barns converted into luxury homes. Here the houses (many modest, some ramshackle) and the roads (largely rutted) seem more like hardscrabble West Virginia than picturesque New England. I'm at the home of Owen Labrie's father, a spry landscaper, musician and copy editor who makes us a killer beef stew for lunch on a cool November afternoon. The house is overstuffed with books and has a single broken, bulky television that looks as if it hasn't seen any action in years. Novelist Annie Proulx of Brokeback Mountain fame once lived here, which somehow seems appropriate. Labrie now has some of the trademark loneliness and despair of the characters in her books, who carry heavy burdens through frigid climes.

"We can stay out a little longer," Labrie tells me after lunch. With glasses, an untucked shirt and a sweater, the 20-year-old has the casual mien of a college student, but Labrie is not in school. He was supposed to be a sophomore at Harvard by now. Instead, he's on a kind of parole, with a strict curfew. The former prep school superstar was convicted earlier this year on misdemeanor and felony sex charges involving a younger girl, and he has to get to his mother's soon, or he'll be subject to arrest. I worry if we're going to make it on time. The sun is approaching the horizon, but he really wants to show me more of his chapel, the one he's building.

Yes, a chapel. Labrie was going to be a divinity student if he'd made it to Harvard. At St. Paul's School, the early Christian texts electrified him, and before his world imploded he'd envisioned life as a rural pastor. "A wife, some sheep, some kids," Labrie had told me a day earlier, as we sat in his mother's curio-peppered house, a wood stove roaring. That scenario seems unlikely now, since most sex offender registries bar things like teaching Sunday school. His chapel is currently just a collection of beams carved with such precision that barely a nail will be needed to assemble them when they're raised like a barn. While it'll look like a chapel, it'll be a half-cabin, half-study where he can write and work. "It's an offering," he says. (Law enforcement mocked it as an effort to suggest piety and elicit sympathy.) I can't help but think, at 12-by-16 feet, it's maybe twice the size of a prison cell.

In June 2014, Labrie, then 18, was accused of sexually assaulting a 15-year-old classmate at the St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire—a charge he continues to deny. (News outlets have abided by the convention of not publishing the name of a sexual assault victim.) The case had everything the media could want. St. Paul's, arguably the nation's best boarding school, was—the press reminded us constantly—a font of power and privilege and prestige. (All press accounts I read used at least one of the words. Most used two.) It's the alma mater of Vanderbilts, as well as the State Department's John Kerry and the occasional eyebrow-raiser like The Breakfast Club's Judd Nelson. The circumstances of Labrie's case were tabloid gold and did not always reflect well on the aspiring minister. There were plenty of emails put into evidence of Labrie wooing the girl, then boasting of "boning" her. In court, he insisted said boning was mere braggadocio, but either way it was a jarring contrast to the young preacher's demeanor that Labrie projects. The young woman testified that she went willingly to meet Labrie in an academic building after hours and stripped to her underwear but then insisted he stop, and he refused. Later, she testified that this left her petrified and suicidal, and she insisted that her friendly and flirtatious notes with Labrie after the encounter were indicative of her own fear, not consent.

In August, a New Hampshire jury offered a mixed verdict that accepted parts of each of their stories. The panel of nine men and three women found Labrie innocent of felony sexual assault but guilty of sexual misdemeanors—basically, of a teen having sex with a slightly younger minor, the kind of charge that rarely comes to trial. (They rejected Labrie's story that he decided it would be a bad idea to take the virginity of someone so young. The prosecution mocked his sudden chastity, and the judge called Labrie "a very good liar.") And the jury did one other thing, something you should discuss with any teens in your life. It convicted Labrie of breaking a New Hampshire computer crime law, one of many enacted across the country in the 1990s, when the Internet went from oddity to necessity and parents began to fear pedophiles enticing their children not only on playgrounds but also on their PCs.

It's an old law that has failed to keep up with the changing times. Like statutes in many other states, it declares that soliciting sex from a minor using computer services is a felony, even if you're a teen. And, like most teens, Labrie used his computer and smartphone to look for love and sex. Had he used snail mail, no felony. Phone call, no felony. Text? No felony. Internet? Felony.

Whitey Bulger's Lawyer

I spent three days with Labrie in Vermont and New Hampshire this autumn. We ate meals and spent time with his parents, who split bitterly and litigiously when Labrie was young, dividing small assets and their son's time between their homes 10 miles apart. Labrie and I would have visited St. Paul's School, but he's barred from the campus and prohibited from calling students, alumni or their families. It was a move the school took before Labrie was found guilty. Some St. Paul's families rallied to Labrie's side, giving him emotional support and donations to a legal defense fund that reached six figures but was quickly depleted when Labrie hired the criminal lawyer who defended Boston mobster James "Whitey" Bulger. The girl and her family found the school unwilling to take stronger action against Labrie beyond banning him from campus. She felt ostracized for accusing a popular boy of a horrid crime and withdrew the following year.

Who to believe, her or him? That schism among students was becoming clear during Labrie's final days at St. Paul's in June 2014. Rumors had begun to circulate that something had happened between Labrie and the girl. Labrie says he thought everything was OK—he and the girl had exchanged kind notes, his wishing that when she loses her virginity it's to someone wonderful. It was not a good sign for Labrie when he emerged from a special chapel service for graduating seniors and the girl's sister slugged him. A few days later, vacationing at a friend's home in Maine, he got a call from the Concord police saying they wanted to speak with him. Questioning followed. Labrie rejected plea offers to serve less than a month in the county jail and receive no sex-related charge. Instead, the case that would be splashed on morning news shows, tabloids and The New York Times went to trial.

Labrie's interviews with Newsweek were his first since his arrest—a chance to explain his life, his hurt, his efforts to rebuild. "I'd do it the exact same way," he says of rejecting the plea deals. "It was the only thing that sustained me, knowing I had told the truth. I had done what was right. I walked out of the courthouse with my chin up." His words might seem to strain credulity, since he had been looking at only three weeks in jail reading books, but he insists that "not caving" was one of the things that kept him going.

Neither the victim nor her family would give an on-the-record interview, but others in the St. Paul's community and in Concord were more open about the case.

While Labrie was restrained in what he said about the incident—his case is on appeal to New Hampshire's Supreme Court—he opened up about his journey from scholarship superstar to unemployed young adult living with his mom, his sentence suspended but subject to conditions such as the curfew. "We can't have a rapist working here," one employer said to him the summer he got arrested in 2014. He gets cursed in hate mail and when he puts gas in his beater of a car. At times, hate yields to madness: Labrie and I watched a YouTube video that depicts him as part of the Illuminati, and the domed observatory at the school's science building, where the incident occurred, as a mosque. There are feminist poems dedicated to his demise and "bro" sites that cheer him for tapping that "skank." Amid the swirling national debates about rape culture and local tensions between Concord and wealthy St. Paul's, it all coalesced in a trial that was about Labrie's behavior but was also a window into things larger than one lanky boy and his theretofore remarkable ascent.

Chaos Theory and Dry Humping

Mistakes never seemed to be a big part of Labrie's life before May 2014. He was born to a couple with little money but plenty of education. His mom attended graduate school at Brown, where she met his father, who had prepped at Phillips Andover, the boarding school famously favored by the Bush family. She is a public school teacher with an earth mother's warmth and a tear-prone frailty; he abandoned academia and has a sly, edgy tone.

A bright, very polite child, Labrie was in ninth grade, attending a private day school, when he learned that his scholarship money was in jeopardy. The dreaded news came just as admission deadlines for private schools approached. Labrie scurried to apply to several, including St. Paul's, where he charmed in a hastily arranged interview, chatting easily about Richard Wright with his African-American interviewer. They gave him a full scholarship.

"I hid my Vermont flannel the first year," he tells me, referring to the woodsy garments that would have marked him as a rural kid from the not-cute part of the Green Mountain State. But Labrie thrived at St. Paul's, one of its brightest stars, which is saying something. It's the kind of place where hyper-ambitious kids spend summers at Mandarin immersion camp and deworming orphans in the Sudan, with a couple of weeks in Nantucket, and make it all look easy. Because the school is so wealthy, it can afford a lot of scholarship students, so Labrie's humble upbringing was noted but hardly unusual, say St. Paul's alumni.

Labrie was captain of the soccer team, rowed crew and started a pond hockey club, renewing interest in the poor man's version of the game at a school with two pro-quality indoor rinks. His grades were stunning. After whizzing through advanced math classes, he took on an advanced study of chaos theory. "It's basically trying to make sense of why things happen," he says, sitting on his mother's couch, noting that it seems an appropriate topic, given the trouble he's in now. But religion "answered more questions" than mathematics. He loved Ralph Waldo Emerson, who had his own problems with Harvard, having been shunned for 30 years for a talk deemed blasphemous.

Despite a kind of nerdy manner, Labrie was smooth with girls. One St. Paul's insider noted that he had plenty of senior girls interested in him almost from the day he arrived. A former girlfriend wrote a note to the judge who sentenced Labrie, asking for leniency, and her parents donated money to his defense fund.

As graduation approached, Labrie had already been admitted to Harvard, and he won his school's top honor, the Rector's Award (later rescinded). In his final days at St. Paul's, Labrie participated in an informal ritual called the Senior Salute. It's not entirely clear when this corny-sounding but profoundly disturbing tradition began and what it involves. Accounts vary, but the basic idea is that during the last couple of weeks of school, graduating seniors (boys and girls) ask younger classmates they may have been too shy or too busy to woo to go on a date. Sometimes those dates are carnal. Sometimes they're chaste. Labrie had his eye on a pretty 15-year-old. On a written list of girls he was interested in seeing, her name was in capital letters.

Labrie wooed the girl for weeks with romantic lines like "The thought of my name in your inbox makes me blush." She demurred at first, citing the way he'd hit on younger girls and noting that he'd dated her sister (the one who cold-cocked him). But she eventually agreed to meet him in the math and sciences building, for which he had managed to get a key. On this the two agree: They made out in the building's noisy and decidedly unromantic mechanical room and were down to their underwear on the floor. She arched her back so he could take off her shorts and raised her arms so he could take off her shirt but, she later testified, was emphatic that she wanted to go no further. "Keep it up here," she recalled saying to him, but she contends Labrie penetrated her with his fingers and penis and tongue, and the jury agreed. He says there was no penetration, only dry humping, and that he decided, after putting on a condom, that he should stop because she was too young.

Romeo and Juliet or Rape?

The trial evidence favored and cast doubt on each of them. Labrie's ugly words to his friends—he quoted a comedian using the word "cum bucket"—made him seem like a cad, if not a predator. That the girl had chatted amiably with him in the days after the encounter, Labrie's counsel argued, was proof of consent. The physical evidence was inconclusive. Labrie's DNA was on her underwear, but that was consistent with his story and hers. New Hampshire is one of a minority of progressive states that don't require women to fight back to prove rape, so the lack of substantial bruising didn't help Labrie. The prosecutors argued that a vaginal abrasion was caused by forced penetration. The defense countered that it was part of the dry hump. The defense tried to use the girl's having shaved her pubic hair as proof she was eager to have sex and cited, as exculpatory, a friend who testified that she heard the victim say she would perhaps perform oral sex on Labrie or let him penetrate her with his finger. The victim denied making those statements.

The verdict reflected the conflicting evidence. The jury threw out the sexual assault felony charge, which was a huge victory for Labrie, but found him guilty of a series of misdemeanors, essentially statutory rape, meaning jurors seemed to believe he'd had intercourse with her. This is a crime that's rarely prosecuted, and when it is, the law has treated it delicately. Most states, New Hampshire included, have sensible "Romeo and Juliet" laws, as they're called, for dealing with young adults having sex with minors. These laws create a necessary distinction between an inappropriate but common case of an 18-year-old having sex with a 15-year-old versus a 40-year-old raping an infant. Labrie was found guilty of breaking the Romeo and Juliet laws—misdemeanor offenses.

Labrie was also found guilty of Section 649-B of New Hampshire's criminal code, which makes it a felony "to seduce, solicit, lure, or entice a child or another person believed by the person to be a child" for sex or lewd behavior on the Internet. It carries a sentence of up to seven years. Most states have a version of that law. The problem for Labrie and the rest of us is that troubling results can stem from it. What teen today doesn't use the Internet to hook up? "If you're two doors away, you're using Facebook," says Labrie's attorney, Jaye Harcourt. "It's an absurd result because the underlying crime wasn't a felony."

The judge gave Labrie a year in the county jail—a lucky break for Labrie, since it kept him out of the much rougher state prison—and suspended the potentially years-long sentence on the Internet charge. But Labrie still had to go on the sex offender registry in Vermont, a life sentence that could affect everything from where he works to where he lives; in most states, sex offenders can't work around kids or live near parks. The former St. Paul's soccer captain might never coach his kid's soccer team. This scarlet "sex offender" tag is part of why Labrie is appealing to the New Hampshire Supreme Court, which may take another year to rule. It could overturn part or all of his convictions. His legal team has yet to shape its arguments, but front and center is likely to be the doctrine of absurd result: A well-meaning law had, through happenstance, led to a cruel—and unusual—punishment.

New Hampshire's attorney general will surely fight the case, and law enforcement has hinted about bringing other charges against Labrie if these get thrown out. (They're looking at the timing of his deletion of Facebook messages, which might allow prosecutors to level obstruction of justice charges.)

Meanwhile, lawyers representing the girl strongly hinted at trial that they're ready to launch a civil suit against St. Paul's School for countenancing the Senior Salute.

If Labrie's case sounds like a crazed legal mess, it is. The media flocked to it because of St. Paul's reputation, but we're in an age where technology and teens can collide in countlessly bad ways at any institution. At a high school in Canon City, Colorado, parents and school officials recently discovered that students had been trading nude photos of themselves and classmates—more than 100 kids and thousands of photographs. The school and parents called the police and prosecutors.

That legal thicket makes the Labrie case look simple. Prosecutors must determine if the student subjects or photographers were underage or adults, if the pictures were taken consensually and if they were traded over the Internet and/or via text. Were they being used to solicit sex or as blackmail? And if some of the pictures ended up on a home computer, are the parents exposed to child porn charges? There's no way to write laws to account for every circumstance, so the best protection is prosecutorial discretion—the wisdom to know what's worth criminalizing and what's best sorted out by families and schools.

You can understand prosecutors wanting to use the Internet predator statutes to widen the scope of their investigation of Labrie. It allowed them broader subpoenas. It was a wrench in their toolbox, and they used it. "But that's a total dodge," says Nancy Gertner, a Harvard Law professor, Democratic appointee to the federal bench and a women's rights attorney who is not the only feminist troubled by Labrie's case, especially how it began as a three-week plea deal and ended up as a felony and a lifetime on the sex registry. "They had discretion."

The last time I see Labrie is at Lou's, a much-loved diner near the Dartmouth College campus. He is wearing a St. Paul's windbreaker. I'd noticed that he would wear St. Paul's attire and occasionally the cap from another prep school. At times, he seemed to fear that it would make it easier for people to recognize him; other times, he wore it defiantly. He'd worn a St. Paul's shirt for his mug shot back in 2014, he tells me, as a signal that he was still connected to the place, even though it was trying to erase his memory. Over vegetarian hash, I tell him I think the email felony sentence, even with its seven-year penalty generously suspended by the judge, was excessive. But I add that I'm not sure what to believe happened that night. He seems disappointed, but as we step into the quaint, misty Ivy League street he is buoyed when a woman stops us and says she believes in him.

A few weeks later, Labrie sends me a video of the chapel-raising, which came a few days after he was formally put on Vermont's sex registry. Labrie and his father and a few neighbors using their muscle to raise the small frame against a darkening December sky may not be the famous Amish barn-raising scene from the movie Witness, but it is touching, a search for permanence, albeit amidst the maelstrom he wrought. (I can only imagine what the victim is doing to recover.) Mastering timber frame joinery also may not be Labrie's greatest accomplishment, but for a young man who may be in jail a year from now, it offers some catharsis.

I call him to ask how he is doing now that the chapel is up. "Outstanding," he says, as we speak by phone around midnight. He says he's getting a little less hate mail and fewer middle fingers. But mostly having the chapel go from "Lincoln Logs," as he puts it, to a real thing has cheered him. Still, he opens up about the crushing debt of his continued legal case. "I try to save some money here and there for the chapel," he says, noting it cost about $1,000 for materials, and that's about the hourly rate of one of his likely appellate attorneys. By the end of the call, "outstanding" has been downgraded to "pretty good." Given his trials, personal and legal, that I believe.