Gina Mullin always kept chocolate in her desk drawer for an afternoon pick-me-up, but a few years ago, in between rounds of chemotherapy, the Hershey's kisses stopped tasting quite right. "I couldn't even swallow," she says. "That's how bad it was."

Mullin, 50 years old and a single mother of three daughters, was diagnosed with Stage II breast cancer in 2005. Seven years later, the cancer returned, this time affecting her brain, liver, lungs and spine, and doctors say she'll need chemotherapy every three weeks for the rest of her life. The aggressive care brings many challenges, but Mullin, once a prolific home cook, says her diminished enjoyment of food is one of the hardest. Years of cycling through treatments have dulled her sense of taste and smell. Everything she eats now needs more spices, sugar and salt, and often that's still not enough to make her food palatable. Each month, a few days after chemotherapy, her mouth is flooded with the taste of metal that makes eating a chore.

This sort of taste deprivation is usually not a priority for physicians treating patients, like Mullin, with often fatal conditions that cause even more obviously debilitating problems, such as loss of motor skills, memory and cognition. The issue, though, is that sensory deficit doesn't just mean burgers taste like cardboard—it can completely destroy appetite, cause patients to lose weight, prompt feelings of depression and isolation, and lead to undernourishment and anorexia. It can become a serious health problem, for which there's currently no solution. "They didn't offer any suggestions at all," Mullin says of her doctors. "When I lost weight, sometimes they would say, 'You know, there's always juice drinks. You can drink and not have to eat.'"

Mullin is just one of millions who at some point experience taste and smell loss. In addition to cancer patients undergoing treatment, the problem also frequently occurs in people with conditions that affect the central nervous system, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis and epilepsy. Sometimes, the deficit is simply a consequence of aging. A recent study in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society that involved 3,000 adults suggests up to half of all elderly people have a poor sense of taste—and it's unlikely that any are getting help.

You Taste With Your Brain

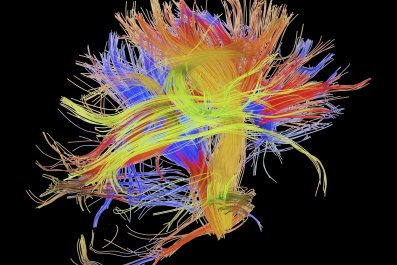

Most people think taste buds in the mouth are the reason eating and drinking are a pleasurable (or sometimes repugnant) experience. However, these tiny bundles of nerves are responsible for only part of the show. Taste buds provide just a single-note experience of what we consume. When food is broken down and dissolved in the mouth—through chewing and the addition of saliva—the particles (tastant molecules) come in contact with taste receptors that detect sweet, salty, sour, bitter and umami (savory). These receptors send the information to the gustatory center of the brain.

But that's only part of the complex equation that makes eating an all-consuming pleasure. When a person eats something, the information from smell, taste, hearing, sight and touch all merge in the orbitofrontal cortex, the central processing center for the five senses. These bits of information incorporate to form the brain's perception of flavor.

A useful exercise is the "nose-pinch test," says Dr. Gordon Shepherd, a professor of neuroscience at the Yale School of Medicine. Try pinching your nose shut and then putting a fruit-flavored candy in your mouth. Chances are, you'll experience only the sugary sweetness of the candy, not its bright, distinguishing flavor (such as orange, cherry or strawberry). "But when you un-pinch the nose, immediately the full flavor that was built into the candy comes flooding into the brain," says Shepherd. The candy's scent helps form the flavor when it's carried from the back of the mouth through the nasal cavity, what Shepherd calls "retronasal smell."

Either way, everyone knows smell is essential to enjoying food—a frequently cited statistic is that it is responsible for between 75 and 95 percent of flavor. This becomes most clear to people who lose some or all of their olfactory functioning, says Shepherd. "They can't get the perception of smell—but even more disturbing, food has no taste other than the sweet, salt, sour, bitter of the taste buds."

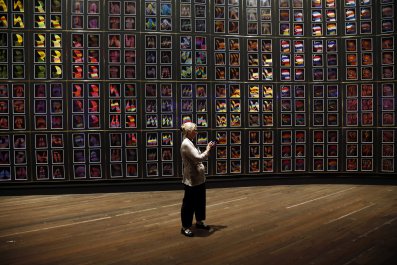

Shepherd, who has studied the olfactory system since the 1960s, found that the olfactory bulb organizes smell molecules in the same way the retina organizes and displays visual fields, then sends signals through the optic nerve to the brain, where it arranges what we see. "Essentially, when we are being stimulated by the molecules that constitute what we call 'smell,' they are creating what I call an odor image, or smell image, in our brains."

In other words, the brain creates flavors. "The food has the elements on which the brain works to create what we sense and call flavor, and that attracts us to the food," Shepherd says. That's an adaptation that keeps us alive: Homo sapiens eat because food tastes good. "I began to realize that humans may be specially adapted for the flavor of the food they eat," he adds. The orbitofrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for flavor, is also linked to learning, memory, emotion, cognition and language—which suggests that flavor perception might be a key piece of many of our higher brain functions.

Shepherd's decades of work have led the way for a growing field of neuroscience research called neurogastronomy (a term he coined for a 2006 paper in Nature), which seeks to understand how all five senses are involved in flavor perception—and what it means when that ability degrades. Today, Shepherd is glad to see that what began as an ambitious research area for academic neuroscientists has fast become an obsession for many clinicians and chefs.

The Meal Rx

Dan Han, chief of University of Kentucky's neuropsychology services, says a new patient recently came to see him because he was suffering from taste and smell loss. The man had already consulted at least a dozen physicians, and none could explain why his cheeseburgers taste like aluminum foil and orange soda like a weird mixture of fizz and gasoline. About six years before, the man sustained mild brain trauma from a car accident that damaged the smell section of his brain. Han explained to the patient that the accident damaged the olfactory bulb in his brain. This area of the brain can heal after a severe blow, but it sometimes leaves scar tissue that permanently distorts a person's sense of smell and, as a result, the experience of food and drink.

Han first got turned on to the power of taste perception in 2012, when he traveled to Montreal for a conference. When Han, a foodie, asked around for dinner recommendations, everyone suggested Joe Beef, a high-end gastropub featured on Anthony Bourdain's popular show Parts Unknown and one of Pellegrino's 2015 top 100 restaurants in the world. Han and his fellow neuroscientists were unable to sit down to dinner until 10 p.m., due to a mix-up with reservations. By then, the kitchen was beginning to wind down, and co-owner and co-chef Fred Morin was making his rounds in the dining room. Morin, it turned out, is fascinated by neuroscience. Before the group knew it, the chef was seated at the table, bringing out plenty of booze and talking about the brain. He'd recently bought a copy of Shepherd's book Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why It Matters, a recommendation from his physician.

Morin and Han realized there could be an opportunity to collaborate. Both wondered what would happen if you put the world's best neuroscientists and culinary experts together. Could that benefit people suffering in silence at the dinner table? It was a novel idea, says Morin. Normally, "the only time when the scientific establishment would collaborate with the culinary world would be if you were catering for a fundraiser." The two made a deal: If Han could get the clinicians and scientists interested, Morin would bring the chefs.

After that champagne-drenched evening, Han returned to Lexington. He wanted to learn more about the clinical prevalence of taste and smell loss, what medical science was doing about it. Two years later, Han, Morin and others in the fields of culinary arts, food science, agriculture and medicine formed the International Society of Neurogastronomy. Based on the pioneering work of Shepherd, the group's stated mission is to "advance Neurogastronomy as a craft, science, and health profession, to enhance quality of human life, and to generate and disseminate knowledge of brain-behavior relationships in the context of gastronomy." The members held their inaugural board meeting and symposium in November, drawing experts from around the world.

Their initial work has prompted projects by many types of specialists with an interest in clinical neurogastronomy, like Edna Schneider, a clinical specialist in neurogenic communication at NYU Langone Medical Center who works primarily with concussion patients. She says many of her patients suffer from olfactory deficits, and research shows people who sustain even mild traumatic brain injury can experience some loss of smell. A study published in Brain Injury that involved 49 patients found 55 percent had impaired sense of smell.

Schneider's work focuses on using memory to stimulate a patient's taste and smell. The underlying concept is that we all begin to experience the flavor of food before it enters the mouth, what's known as the anticipatory or pre-oral stage. Schneider selects a pungent taste or smell, such as mint, and instructs the patient to spend a week with it. That means smelling fresh leaves, drinking herbal tea, adding mint flavor to food and cooking with it. She asks the patient to keep a journal detailing memories of the flavor and smell, playing upon the idea that what we eat is also attached to deep emotions. Schneider says the journaling, combined with taste and smell exposure, appears to boost the confidence of her patients when it comes to enjoying food. "They're cooking more. They're entertaining more because they feel more comfortable with food and social engagement," she says. That, in turn, leads to an overall improved quality of life.

Morin, meanwhile, is focused on mobilizing what he believes is the best weapon to fight taste deficits: chefs. "There're people out there who can 'give' appetite—they're like stomach whisperers," says Morin. The problem, though, is that "these people are in the restaurants; they're not in the hospital." He's now in conversations with food service companies about developing meals prepared with ingredients that address smell and taste loss in patients. These meals could then be delivered to patients as an alternative to standard hospital fare.

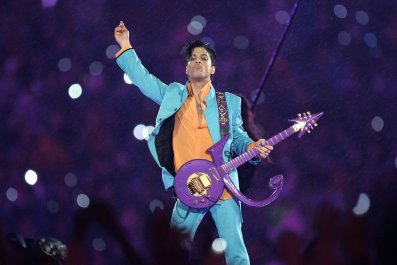

Morin has also developed a sort of prescription for tailoring meals to suit the taste- and smell-challenged. At the symposium, Morin and other chefs demonstrated: He took a bland potato soup, an archetype of the slop served to a convalescing patient in a hospital, then fancied it up with some greenery and chicken skins seasoned with barbecue spices. He has a clear vision of what works best to help those with taste and smell loss keep their appetite. For example, the emphasis should be on preparing foods with a pleasing texture. He serves a soft meat with plenty of connective tissue and collagen, such as slow-braised lamb shoulder. He also avoids ingredients that contain chemicals responsible for distinct sensations such as cool, hot, tingly and pungency. Mint, jalapeño pepper and carbonation, to name a few examples, create what's known as chemosensory irritation, the detection of chemical irritants in the nose, mouth and skin . This sensory system acts independently from smell and taste and is carried by the trigeminal nerve, which transmits sensations from the face to the brain. In a person with taste and smell loss, something like wasabi-spiked soy sauce or fresh chilies doesn't properly integrate with the olfactory and gustatory system and only causes irritation.

How food is served also matters. It doesn't take a culinary genius or neuroscience Ph.D. to understand how presentation can make a meal more pleasing, and corporations make billions simply by developing clever and eye-catching packaging for food that on its own is less than tempting. Morin says aesthetically appealing plating and accommodating service are essential to creating an enjoyable dining experience. The right ambiance for people who have issues with taste and smell perception is "lively and boisterous," he says. Food is best if it's served family-style in the middle of the table and requiring assembly to make mealtime a more interactive experience—for example, dishes should be served with a selection of condiments so everyone at the meal can choose their own. "Sometimes, having your own plate is a little bit like having the spotlight on you. You're on camera, and if you don't finish it then people look."

Charles Spence, a professor of experimental psychology at Oxford University, is investigating how plate color can influence whether a person eats only one bite or finishes a meal. For example, he says research shows people rate ice cream as 10 percent sweeter and 15 percent more flavorful when it's served on a white plate rather than a black plate . In the real world, the impact of plate and utensil color on appetite is generally ignored, with potentially disastrous results. For example, some hospitals in the U.K. have a "red tray regimen," meaning patients preparing for specific procedures receive their food on red trays. It's a signal to health care providers that the person requires special care. However, red is possibly the worst color for encouraging food consumption. One study published in 2013 in the medical journal Appetite found that when people were served food on a red plate and beverages in a red cup, they cut calorie consumption by 40 percent—even when the researchers topped the plate with chocolate. The researchers hypothesize that red plates may lead people to eat less because the color is universally associated with stop signs and danger.

Much of the work done on sensory integration and flavor perception has occurred in labs, highly controlled and artificial environments. Spence is trying to change this. He sees his work as "moving away from the brain scanner study of flavor perception to a more realistic gastronomy"—he calls his approach "gastrophysics," a multidisciplinary approach drawing from behavioral economics, psychology, sensory science and food science. "It's much more about trying to test people in the hospital setting, in cafeterias, restaurants and home dining to see what really matters in those environments," says Spence. He's conducting research with Sant Joan de Déu, a children's hospital in Barcelona, Spain. Children undergoing chemotherapy and radiation often refuse to eat because food, to them, has a metallic taste, so Spence and his team are testing whether plates of certain colors can motivate them.

He also suspects patients might deal better with the metallic taste if they're introduced to it well in advance of their cancer treatment. It'd be something like wearing an elevation training mask that reduces your oxygen flow while you hike around California in order to acclimate to low oxygen environments before you try to climb in the Himalayas. For cancer patients, the trick would be to introduce the metallic flavor in a comfortable setting, such as home or a restaurant, so it isn't " associated with pain and stress and suffering ," says Spence. "If people were first exposed to the taste of metallic away from the hospital context, could it then be that they perceive it differently?" He is working to develop a metallic meal with Jozef Youssef, a chef known for his experimental, multisensory dining experiences.

Money From Your Tummy

Those in the emerging field of neurogastronomy feel a kinship to pioneering sexologists William Masters and Virginia Johnson. In the 1950s and '60s, the pair forever changed our understanding of human sexuality at a time when patients were embarrassed about sexual dysfunction, which wasn't considered a clinical problem. "Masters and Johnson said, 'No, this is the science of life,'" says Han. "Next thing you know, 40 or 50 years later, not only is it a legitimate science—it's a trillion-dollar industry."

The medical world is slowly coming around to the fact that a patient's ability to enjoy food is not just a triviality—and it's likely that there's money to be made in neurogastronomy. Han and his colleague Tim McClintock, a professor of physiology at the University of Kentucky, are collaborating on research that could result in pharmaceutical drugs to reverse taste and smell loss.

Smell processing begins at the epithelium, a strip of tissue at the back of the nose that holds sensory neurons (or receptors). Each one contains proteins that attach to different odor molecules when they float by. McClintock has developed a test that can detect which of the 1,100 mouse odor receptors are activated by certain odor molecules. He is still developing a way to translate this test for humans. Ideally, that would involve inserting all 350 human olfactory receptors into the mouse genome to conduct the same test; while costly, it is likely possible. The research could be applied to develop drugs that enhance flavor for those who suffer from taste or smell loss.

But his research could also point to a way to alter flavor for people with normal smell and taste functions. "One of the things our technology will eventually be used for is to transform how we develop new flavors, better flavors and, more broadly, new odors and new odor modifiers," says McClintock.

Take, for example, durian fruit, commonly eaten in Southeast Asia. It's known for a stench so unbearable that it is banned from Singapore's mass transit system. But durian also happens to be exceptionally nutritious. McClintock says his research may one day lead to the development of blockers for certain receptors involved in detecting these malodors, instantly making durian more palatable. The possibilities of such an advance are endless; the future of food could one day include broccoli that tastes like chocolate.