First, there was disbelief.

When the news first trickled onto Twitter shortly after 11 a.m. Minnesota time, the details were hazy: a death at Paisley Park, an ambulance, fans gathered outside. We didn't believe that Prince had died, because our collective cultural conception of Prince required us to believe that Prince couldn't die. When you saw him floating in that misty bathtub in the "When Doves Cry" video, you wondered what planet he had arrived from, not whether he might get the flu.

If this sad year in music has taught us anything, it's that this is an illusion—they all die, even the most mysterious, otherworldly icons, the ones who've always seemed immortal.

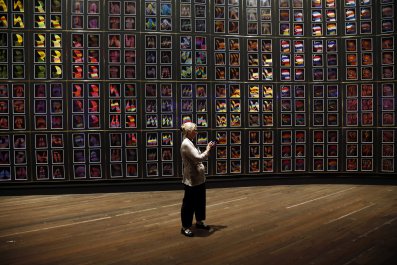

Prince fans are by now accustomed to disbelief, though not of such a mournful variety. Disbelief is what happens when you read the album credits for Dirty Mind—the raw 1980 coming-out party for Prince's freakier side—and see that Prince wrote, produced, sang and performed every instrument on every song by himself, save for a backing vocal and synthesizer on two tracks. Disbelief: When you try to wrap your mind around the fact that Dirty Mind, Controversy, 1999 and Purple Rain (each a masterpiece) all popped out one-by-one in the span of less than four years. (This is the best consecutive string of albums in pop music history, though that's an argument for another day.)

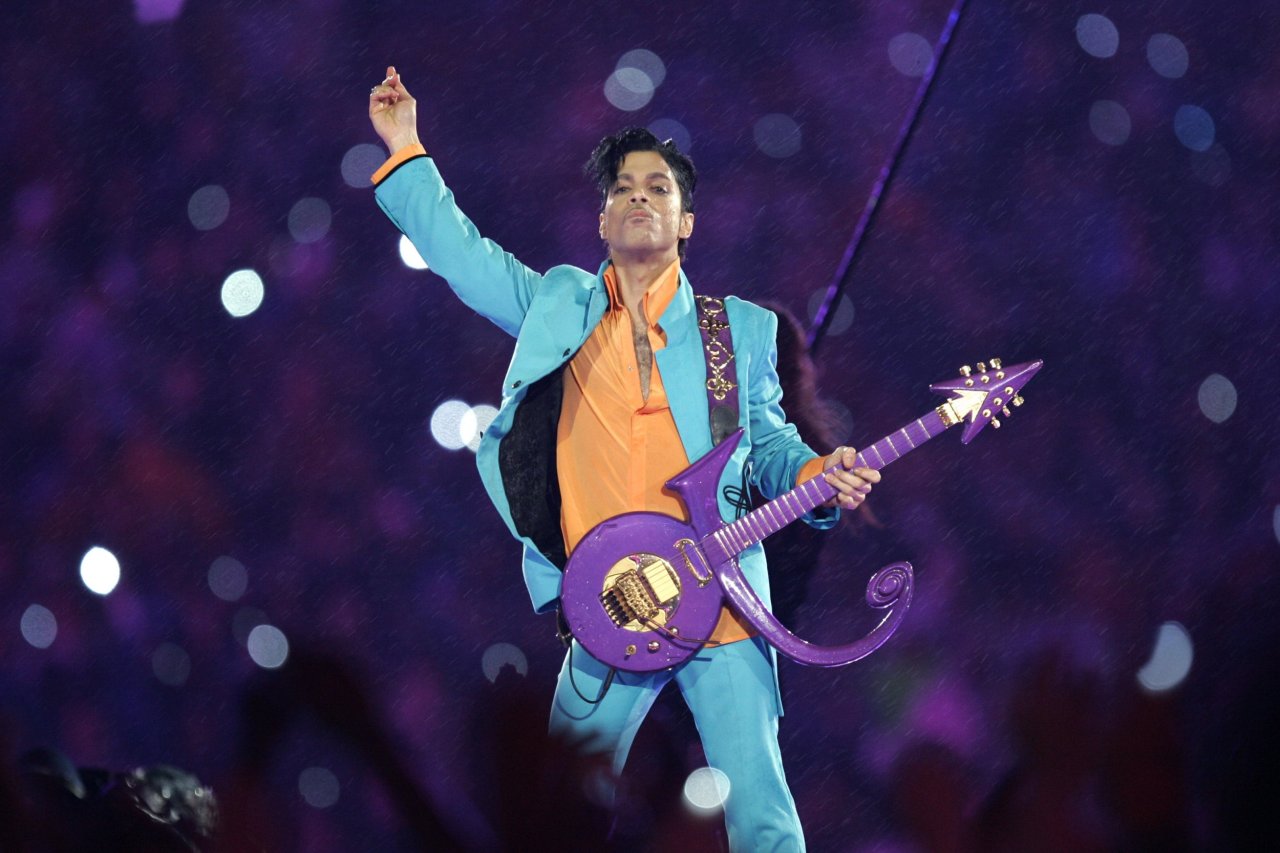

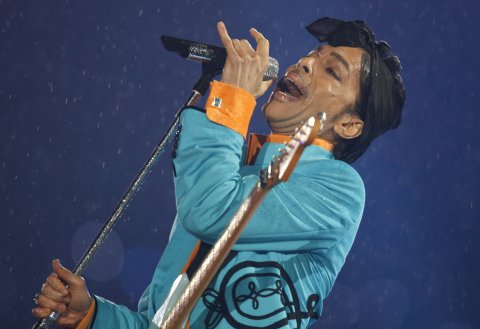

Disbelief: The only rational response to Prince's 2007 Super Bowl performance, when he closed with a shimmering performance of "Purple Rain" as a purple-tinted downpour streamed down from the skies above him. Even non-fans grudgingly admit this was the best halftime performance ever.

Disbelief, evidently, is what struck Tipper Gore when she caught her daughter listening to 1984's "Darling Nikki." "I couldn't believe my ears!" Gore later recalled, apparently not meaning it as a compliment. The gloriously erotic cut, which describes a funky tryst with a self-pleasuring "sex fiend" named Nikki, enraged Gore so much that she cofounded the Parents Music Resource Center and spent much of the mid-1980s lobbying for stricter labeling of explicit lyrics. Prince's sexuality was brash and shocking—he sincerely wanted to fuck the taste out of your mouth—but it was also empowering. He softened the edges of his own masculinity and soundtracked thousands of fans' sexual awakenings, whether straight or queer.

With inhuman grace, fearless sensuality and intergalactic funkiness, Prince expanded the realm of what is or might be possible for a pop star to accomplish—and he made it look easy. Like David Bowie (who, in some cruel twist of fate, preceded Prince in death by just three months) he toppled barriers of gender, genre, race and, mostly, imagination. His influence is as boundless as the Emancipation track listing, though it's still worth rattling off a few names. Without Prince, there'd be no Outkast, D'Angelo or Miguel. He changed Questlove's life and inspired Stevie Nicks to write "Stand Back." His rivalry with Michael Jackson challenged both stars to up their game, even as Prince shrugged off opportunities to team up with MJ. He inadvertently lifted Sinéad O'Connor to fame with "Nothing Compares 2 U," and he championed his own protégés, from Vanity to Morris Day. And we can see glimmers of his iconoclast stubbornness in the career of Kanye West, particularly West's recent aversion to conventional release strategies (think Prince circa 2001).

Prince re-wrote the rules of pop music in the early eighties, when he crossed over from a primarily African-American R&B audience to the purple-coated throne of mainstream pop, and then he rewrote them again. And again. And then again. He made Purple Rain, a historic fusing of the sacred and profane that's basically the handbook to give to an alien who wants to understand late-20th century pop. He showed us that "pop superstar" and "guitar genius" are not mutually exclusive. He built a stark, mesmerizing number one hit without bothering with a bass line ("When Doves Cry"). He wrote pop songs about incest ("Sister" isn't subtle), nuclear annihilation ("1999") and gender-bending fantasies (the sublime "If I Was Your Girlfriend"). He made Sign o' the Times, a double LP that's become synonymous in the critical lexicon with any sprawling, freewheeling statement by a genius at the peak of their powers.

As Prince retreated deeper into his weirdness, the star's eccentricities began to distance him from the mainstream audience he'd won over with "Purple Rain" and "Kiss." The late eighties, in retrospect, marked a turning point: The Black Album, a would-be follow-up to Sign o' the Times, was abandoned at the last-minute, either because of a bad ecstasy trip or a spiritual epiphany that convinced Prince the album was evil, depending on whom you believe. Lovesexy, the intensely spiritual album we received in its stead, contained some serious jams, though if you owned it on CD you had to deal with one uninterrupted, 45-minute track. (You only need to fast-forward six minutes to hit "Alphabet St.")

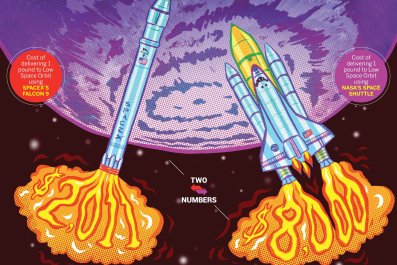

The 1990s were more fraught. As Prince became embroiled in a bitter war with Warner Bros., he changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol and released a string of barely marketable albums that run the gamut from surprisingly excellent (The Gold Experience) to miserable (Chaos and Disorder). He retreated deeper down the Paisley Park rabbit hole after 1999, releasing several little-heard albums that were exclusively available via his internet subscription service. This was also a turbulent period in Prince's personal life. The artist's three-year marriage to Mayte Garcia, 15 years his junior, led to heartbreak when the couple's infant son died from a rare genetic disorder.

But something curious happened in the final years of Prince's life: He came home. Musicology, from 2004, along with its accompanying tour, is commonly singled out as the comeback moment. But the real work of introducing Prince to a younger generation came later. Despite Prince's famously ambivalent relationship with the internet, the digital arena has been a powerful sphere for Prince appreciation. In recent years, clips like that Super Bowl performance, the "Breakfast Can Wait" video and Prince's legendary Coachella cover of "Creep" seem readymade for the viral era. Prince's recent award show appearances were like manna for meme-makers. And with his late embrace of Twitter and Instagram (or "Princestagram"), he began to speak to fans directly, albeit as mysteriously as ever.

Prince was active up to the very end, which is part of what makes his death so puzzling and shocking. His thirty-ninth studio album, HITnRUN Phase Two, hit Tidal at the end of 2015. He then spent the early months of 2016 plotting and performing his stripped down Piano & A Microphone Tour. He played as recently as a week ago, incorporating a cover of David Bowie's "Heroes" into his set.

And he made a rare appearance at a Paisley Park dance party last weekend, addressing fans in the wake of rumors about his being rushed to the hospital the prior day. "Wait a few days before you waste any prayers," the Purple One reportedly said.

Rest in Purple, Prince. And if the elevator tries to bring you down: Go crazy.