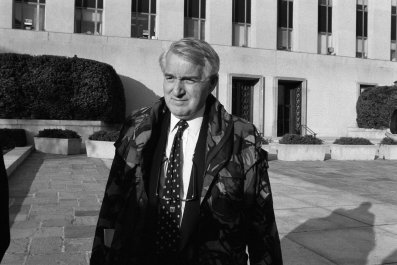

It was no coincidence that the leak came just a week before Defense Secretary Ashton Carter set forth in April on a high-profile trip to Asia, which would include a helicopter flight to a U.S. aircraft carrier sailing through disputed waters in the South China Sea. According to a detailed account in the Navy Times, the U.S. Pacific Command's chief, headquartered in Honolulu, has become increasingly agitated not just by China's boldness in installing military facilities on islands it has constructed in the South China Sea—in waters claimed by other countries—but also at what the commander perceives to be a wholly inadequate U.S. response to Beijing's behavior.

According to the piece—not denied by anyone subsequently—the commander, Admiral Harry Harris, has proposed "more aggressive, frequent and close patrols," within 12 miles of islands that Beijing has constructed far from its borders—what Harris has called "the Great Wall of Sand." According to the article, Harris wants to do this before Beijing builds another island just 140 miles off the coast of the Philippines, an atoll known as the Scarborough Shoal that is well within the Philippines's 200-mile economic exclusion zone.

Carter's trip was meant to reassure smaller countries in the region—particularly the Philippines—that the U.S. was on the case. He marked the end of 11 days of joint military exercises with Manila by announcing that both the Navy and the Air Force would begin joint patrols in the region and said the U.S. would add a residual force of about 200, as well as six new aircraft and three helicopters, to the islands.

It is not at all clear that Carter did much to further Washington's goal of reassuring its allies. Beijing also has made clear in recent weeks its determination not to back down in the South China Sea. During the nuclear summit in Washington at the end of March, President Xi Jinping told President Barack Obama that he would not allow any challenges to Chinese sovereignty in the region. And just before Carter's trip, the highest uniformed officer in China's military, General Fan Changlong, visited the Spratlys, a sprawling collection of islands not far from the Philippines, parts of which are claimed by Manila, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia and Brunei.

The fear in the region, never stated publicly, is that Beijing, in the closing months of the Obama administration, will increase the pace of its military buildup in the region, secure in the knowledge that it is unlikely to be confronted. Diplomatic and defense sources in two countries said that while Carter's trip was important, the U.S. Navy's response to Beijing thus far has been "a little confusing," as one put it. Patrols to date that have come within 12 miles of Beijing's newly constructed islands (that is, in Beijing's view, within its territorial waters) have been conducted, as the Navy Times piece noted, under the doctrine of "innocent passage," which precludes the use of aircraft, weaponry or anti-aircraft systems during a voyage. Far from sending a signal to Beijing that Washington is confronting China, the concern in the region is that such patrols have only reaffirmed the view that China does have sovereignty over newly constructed islands.

For what it believes are good reasons, the White House has resisted Harris's calls for a more robust response. It seeks cooperation with Beijing on a host of issues that are important to Obama—from climate change and trade to dealing with what Washington sees as an increasingly unpredictable Kim Jong Un in North Korea. Ratcheting up tension in the South China Sea would put cooperation on those and other issues at risk, administration officials say.

Containing China?

This has been the administration's dilemma from the outset: Once it announced its so-called pivot to Asia, in which the U.S. would pull back from the Middle East and deploy military and diplomatic resources to a region it decided was more important to American interests, it has reassured Beijing that the move was not about "containing" China. Yet to anyone in the region with eyes and ears, it is plain that, in part, the so-called "pivot" was about containing China. How could it not be?

Precisely because Xi has put on a show of force in the region, smaller countries already well within China's economic orbit have increasingly looked to Washington. Beijing's insistence that its map of the South China Sea—known as the "nine dash line," which basically paints Chinese sovereignty over nearly the entire region—be heeded by everyone has scared the hell out of countries inclined to be friendly to China (Singapore, for example), as well as those that historically have been distrustful (Vietnam).

There is a widespread consensus among diplomats and analysts in the region that Beijing has played this hand poorly; that it has stirred real concern where it needn't have; and that its economic weight alone was carrying the region in the direction it wanted—that is, into its sphere of influence. But Beijing, to the alarm of some who had to until then been unconcerned by its rise, doesn't appear to care what anyone else thinks. And that could mean further trouble to come.

This June, for example, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague is due to rule on a case brought by Manila against China's claims in the South China Sea. If, as appears likely, Manila prevails, tensions in the region will intensify. "China will surely not bow to the pressure brought by the final judgment of the tribunal," Kang Lin and Jiang Zongqiang, research fellows at the China National Institute for South China Sea Studies, in Haikou, wrote recently. It will, first, likely try to resolve the territorial disputes bilaterally—which means, practically speaking, it will try to bribe or coerce its way to get what it wants: de facto recognition of its expanding regional claims.

But it's not clear that its neighbors will play along. There is some talk that other nations may file similar claims in the wake of a favorable ruling for Manila. If that happens, Beijing's response is unpredictable. And once again, smaller countries in the region will turn to Washington for more reassurance than they have received so far. The Pentagon, we now know, would like to provide it, but it's hard to believe the administration, eager to get out the door without having to deal with yet another foreign policy crisis, will agree to anything that seriously jacks up tensions with Beijing. It's going to be a very tense summer in East Asia.