When Angolan journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais visited a morgue in the city of Luanda in March, he saw 235 bodies being carried out in five hours. The crowded Angolan capital, chaotic at the best of times, was in the throes of a massive outbreak of yellow fever and malaria, and by Marques's account, it was hard to say who was dying of what. "People died of one disease, and [hospital staff] would write down another," he says.

Angola has been grappling with its worst yellow fever outbreak in three decades, a crisis that the World Health Organization (WHO) recently warned "constitutes a potential threat for the entire world." The big fear is it could spread to China, which has been free of the virus, if Chinese workers return home sick, and supply of the vaccine is already under pressure.

At least 250 yellow fever deaths and nearly 2,000 cases have been reported in Angola since December, but Marques and others think the numbers are higher. The epidemic took hold in the densely populated capital of Angola, where the global collapse in oil prices led to spending cuts on public health and sanitation that, along with unusually heavy rains, created a fertile environment for the deadly virus's favorite transmitter, the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

The effort to care for and vaccinate millions of Angolans has strained hospitals and put unprecedented pressure on the world's supply of yellow fever vaccines. Infections linked to Angola have already been seen in Kenya, Morocco, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and China, raising concerns over whether there will be enough vaccine if the outbreak spreads to another big city. "I hate being a scaremonger, but this thing really scares me," says John Woodall, a retired virologist and co-founder of the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases. "Everything is brewing up for a perfect storm."

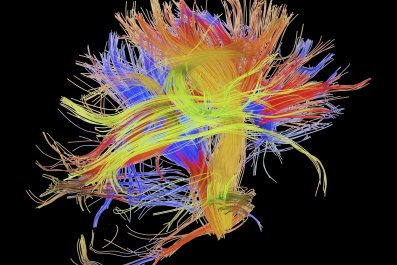

Epidemiologists have always been very concerned about yellow fever because, if untreated, it can kill up to half of severely affected patients. It is endemic in over 40 countries in Africa and Latin America and kills up to 60,000 people every year. The virus is transmitted when a mosquito bites an infected person and then a healthy person. Cases where the virus is imported by a sick person had never been reported in Asia until March, when one of the thousands of Chinese workers in Angola came down with chills, flew home and was diagnosed with yellow fever in Beijing. In total, 11 cases have been confirmed in travelers to China from Angola, stoking fears of a potentially disastrous outbreak in Asia, where the A. aegypti mosquito is common.

Companies doing business in Angola are taking precautions. Though a government-led vaccination campaign is underway, the Luanda Medical Center, a private facility in the capital, was approached by a large construction company in mid-April to help buy 4,000 doses of the yellow fever vaccine for its workers. "It's a little bit of a corporate concern," said Michael Averbukh, CEO of the center, which has already purchased some 6,000 vaccine doses for other clients. "They just want to make sure all their employees are vaccinated."

In addition to China, experts are concerned about an outbreak in Angola's neighbor, the DRC, where 10 yellow fever cases linked to the Angola outbreak have been confirmed. "If anything happens in [the DRC capital] Kinshasa, then there will be even greater competition for the vaccine doses," says Ebba Kalondo, a WHO spokesperson in Angola.

The vaccine for yellow fever is safe and reliable, but there are problems with supply. Over 9 million doses have already been sent to Angola, including the entirety of a global emergency stockpile that is kept on hand each year. Some 15 million more Angolans still need to be vaccinated, with cases now being reported in several provinces. "This is probably the first time that the entire yellow fever emergency stockpile was depleted," says Justin Williams, a public health adviser for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Ramping up yellow fever vaccine production is difficult, partly because only a handful of manufacturers make it, in a process that requires six weeks to grow the vaccine in chicken embryos. The global emergency stock has been topped up by drawing from other nations' routine immunization supplies, a fix that has prompted its own concerns about immunization programs in other countries in the event of a shortage. "If there was another outbreak, you'd have a problem," says Thomas Monath, who leads the infectious disease division at Iowa-based NewLink Genetics.

One workaround could be a low-dose but effective version of the vaccine. It's an option that would make large quantities of the vaccine available faster and cheaper. But, says Woodall, persuading the public that a diluted vaccine is just as effective may be difficult.

For now, endemic countries need to tighten up on checking travelers' immunization records, experts say. International law requires people entering Angola and other yellow fever endemic regions to carry a card indicating they have been vaccinated, but, Monath notes, "these laws are widely ignored." There's even a trade that's developed in fake vaccination certificates. When the Angola outbreak erupted, some people who were infected were holding fake proof of vaccination, complicating early efforts by doctors to pin down what disease they were looking at, says Hernando Agudelo, the WHO's country representative in Angola.

It's not unusual for yellow fever vaccines to be in short supply, and it's hard for public health experts to predict an outbreak. Monath says there's not a lot of commercial incentive for more pharmaceutical companies to produce the vaccine, which is less than $2 a dose. The disease is also competing with other threats, like the Zika virus, for funds and attention. Woodall, the virologist, explains, "Just like it's difficult to fight two wars overseas at a time, it's difficult to fight two epidemics at a time."