One the most popular exhibits at what may be Australia's most remarkable museum stinks—literally. Composed of glass amphorae that gurgle with unappetizing liquids, the artwork is called Cloaca, and in addition to a steady stream of foul odors, it emits a solid piece of waste about once a day. Cloaca is, in other words, a poop machine. A poop machine that, as part of the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Hobart, has helped to completely transform tourism in the island state of Tasmania.

For much of its history, Tasmania was known primarily for its sheep and its prisoners. Occupied by Aborigines for an estimated 40,000 years, it was invaded in 1803 by the British, who turned it into a notoriously harsh penal colony and developed the wool, mining and timber industries that remain important sectors of the Tasmanian economy today. Tourism, when it developed, revolved largely around the island's spectacular natural beauty—its beaches, rainforests, Alpine mountains and abundant wildlife.

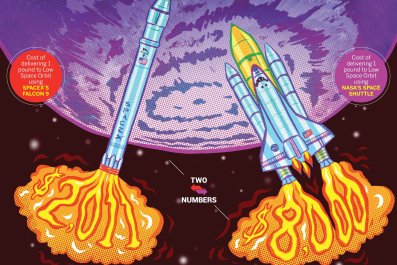

But all that changed in 2011, when a professional gambler—who made his fortune by developing a sophisticated and (so far) reliable system for betting on horse races—with a penchant for the provocative opened MONA. After constructing a striking, sharp-angled building on a stretch of coastline about 15 minutes outside of Hobart, the capital, native son and millionaire David Walsh then stocked it with a combination of ancient sculptures and decidedly contemporary pieces from his private collection.

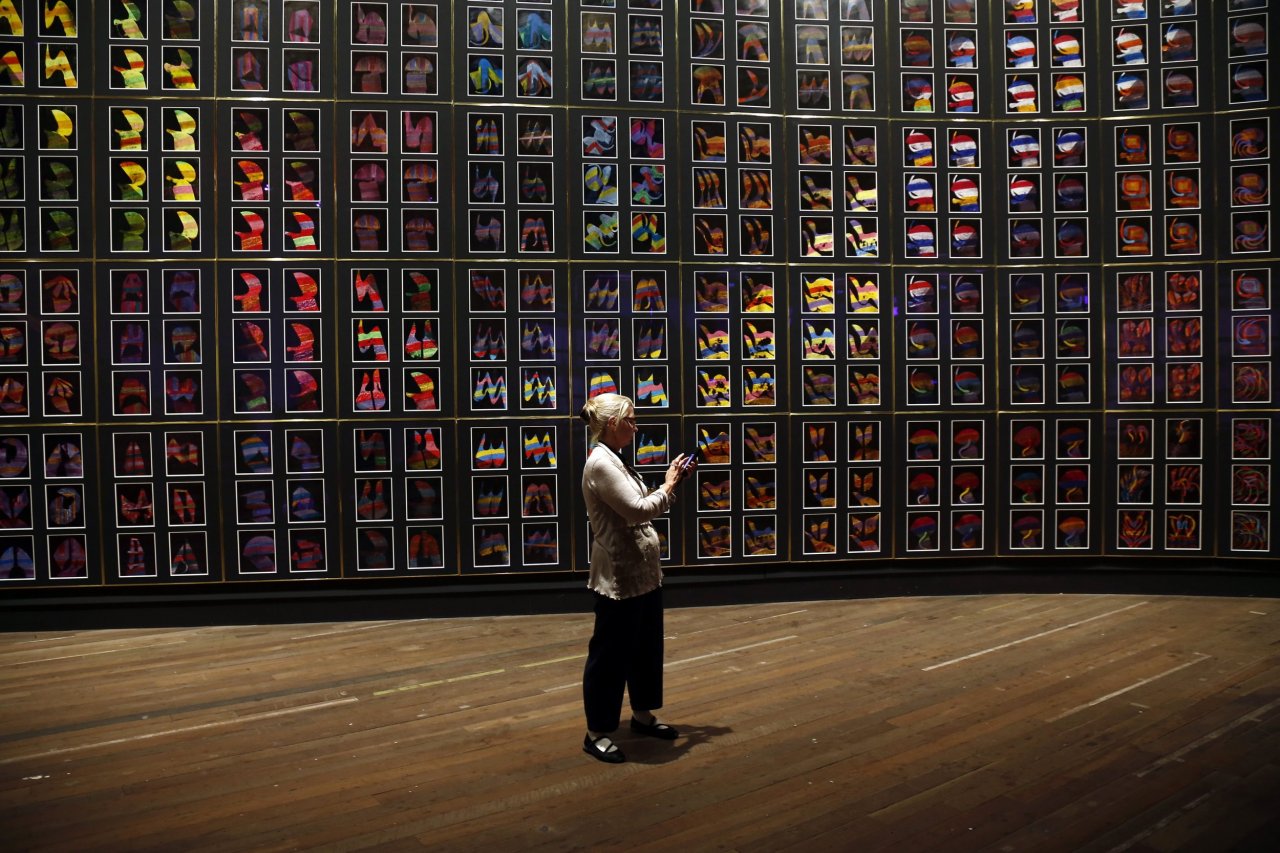

MONA is deliberately unconventional. Its galleries are underground; the lighting is dim in places and creates a sometimes menacing feeling. And many of the works, in an institution that is only somewhat jokingly referred to as the "museum of sex and death," are intentionally provocative. One piece, for example, consists of a display of plaster casts of female genitalia, while a recent temporary exhibit was a retrospective of wry, thoroughly scatological work by British artist duo Gilbert & George.

But MONA is entertaining in other unique ways. There is no wall text here; visitors receive a tablet device that senses when they are near a given work and allows them to choose the kind of explanation they prefer—short, in-depth or "gonzo" (impressionistic riffs on a work, often by Walsh himself). There is a bar in the basement and bright pink beanbag chairs outside for enjoying the view. One work, a video installation composed of 30 screens, has individuals each singing every song on Madonna's Immaculate Collection album.

Tasmania is not the first place to see its fortunes transformed by a spectacular cultural institution. Ever since 1997, when the Guggenheim opened a branch in a Frank Gehry–designed building in the Spanish Basque capital, Bilbao, other parts of the world, from Brazil to Inner Mongolia, have aimed for their own Bilbao effect. But MONA isn't a civic project.

"Bilbao made a strategic decision to get the Guggenheim and launch a regeneration process," says Justin O'Connor, professor of communications and cultural economy at Monash University. "David Walsh just dropped MONA on an unsuspecting city [and] state. Ever since, they've been trying to retrofit their thinking around its enormous presence."

About 30 percent of Tasmania's 1.15 million visitors last year went to MONA, contributing an estimated $100 million to the local economy, according to the state's Tourism Industry Council. At first glance, the effect of the museum's visitors isn't obvious. In contrast to the wild landscapes that dominate the island, Hobart is a tranquil, manicured city, its central streets still populated with an appealing mix of Georgian homes and industrial warehouses. But a growing number of enterprises cater, with varying degrees of edginess, to the culture-minded tourists drawn by the museum.

The Henry Jones Art Hotel, built into what was once a wharf-side jam-packing factory, predates MONA. But its theme—both its public areas and its sleek guest rooms are hung with works by contemporary Australian artists—has made it the accommodation of choice for many of the 334,000 annual visitors to the museum. "What I see is that nearly everyone who stays here goes to or inquires about MONA," says Jackson Sutherland, a concierge at the hotel. "In fact, we get lots of people who just stay the one night. They fly in, go to the museum and fly out."

For those who stick around, there's plenty to see. Hobart is home to about 20 art galleries, including Despard, which specializes in contemporary art, and Art Mob, which showcases aboriginal works. Several more are housed in the Salamanca Arts Center, a sprawling complex built in Georgian warehouses that also includes theaters, arts administration offices, craft studios and the sort of carefully curated shops—all muted natural fabrics and handmade cheese—that populate the pages of the hipster, slow-lifestyle magazine Kinfolk.

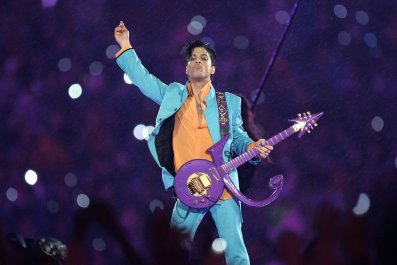

There are new constructions too, like the Brooke Street Pier, a floating building that houses the port for the ferry to MONA and is home to two ambitious restaurants and several tiny boutiques. MONA hosts two art and music festivals a year, including one in midwinter, called Dark Mofo, that spreads out its carnivalesque tentacles into the city. In its latest incarnation, Dark Mofo featured talks with artists, including Marina Abramovic, experimental performances, a five-day communal feast, a flame-throwing musical instrument and an annual nude swim on the longest night of the year. About 130,000 people attend Dark Mofo annually, 28 percent of whom come from outside of Tasmania.

But it's not just tourists who are flocking to the state. So too are artists, writers, musicians and other creative types. In fact, Tasmania has the highest percentage of people employed in the arts of any state in Australia. The MONA effect "has encouraged people to relocate," says O'Connor, who has studied the phenomenon. "It's allowed creatives to spend more time here, built synergies with existing institutions and—most important—changed the way people think and dream in Hobart and Tassie."

David Moyle is one of them. Originally from Victoria, on mainland Australia, he moved to Tasmania for what he thought would be a temporary gig as a consulting chef at a resort called Peppermint Bay. He's still in Tasmania, after opening a new place in 2014 called Franklin, which is housed in the renovated former newsroom of what was once Hobart's daily paper. "It's an appealing place to live," he says. "The industries based on extraction of resources have failed, and creative industries have stepped in to become the driving force."

With a menu that features local ingredients like abalone, and many dishes prepared in a wood-burning oven, Franklin has been proclaimed one of the best restaurants in Australia by Australian Gourmet Traveller magazine. Moyle believes the presence of MONA has helped businesses like his get started. "The museum gives you confidence that there's enough people coming through who want quality. I don't think the restaurant could have existed without it."

The MONA effect, however, is not universally acclaimed, especially when rampant development threatens. Six new hotels, promising a total of 800 rooms, are either under construction or in the planning phase, including one that somewhat ironically would oust the Tasmanian College of the Arts from its current location. A major new development that will combine apartments, offices, shops, restaurants and public spaces (the latter are being designed in consultation with MONA) is going up next to the recently renovated cruise terminal. And some arts institutions find themselves competing with Walsh's powerhouse for funding and influence.

Although it predates MONA by several decades, the Salamanca Arts Center, for example, sometimes has to defend itself. "MONA has been hugely positive for the state in many ways," says Salamanca spokeswoman Briony Kidd. "But there's an entire infrastructure of Tasmanian cultural activity that's specific and unique to this place, and it all needs to be recognized and supported."

Tasmania's ability to navigate the changes brought on by Walsh will be tested again in the not too distant future. In a nod to the origins of his fortune, he will soon open a casino next to the museum. That enterprise, which will be aimed at high rollers, may change the nature of tourism to Tasmania again.

For as long as MONA continues to explore the overlap between art and entertainment, it will surely grow. Late last year, the museum installed a James Turrell work called Amarna on a hill outside the galleries that changes colors with the rising and setting of the sun—the museum refers to it on its website as "what God would do if He decided to build a gazebo." Every week, the museum holds a gourmet dinner for patrons beneath the gazebo. Because the installation is outdoors and access to it is free, some visitors take matters into their own hands. Research curator Delia Nicholls recalls one evening when a couple of young men brought a pizza and a six-pack to Amarna at sunset, only to find themselves joined by a very pleased Walsh. "David always said he'd be happy when 2 percent of the world's art lovers come," Nicholls says. "But that group keeps growing."