As Americans regularly shirk the advice of their doctors, a band of pixelated castaways and a flightless dragon may be a care provider's best bet to get patients interested in their health.

Has care become too boring? An armchair review of U.S. therapy practices and the underlying research gives the impression that some of our worst public health problems shouldn't be that bad—the past century brought with it groundbreaking cognitive and physical rehabilitation treatments that slash complications of head trauma, joint injury and psychiatric disorders. Extrapolate from clinical research and the battle against many of these conditions appears to be all but won. However, if you ask any clinician or researcher, you'll probably be told the opposite.

Consider, for example, incidents of falls among the elderly—a threat so common it has spawned its own industry of nonmedical measures like alarms and other at-home applications. For adults 65 and older, falling is the most common cause of fatal injury and brain trauma, with one-third of the elderly population suffering an incident each year. This jarring stat hardly reflects the promises of current recommended risk-reduction programs, many of which tout stellar outcomes in trial environments. "There have been clinical trials around the world showing that if people just did these exercises, they could reduce their risk of falling after the age of 65," Sheryl Flynn, a physical therapist and researcher in motor learning and control, tells Newsweek. "The problem is that nobody does them."

Therapists observe this sort of lack of adherence across the spectrum of care: Older adults stick balance programs on the fridge and forget about them, kids with ADHD leave attention exercises at school, and paraplegics fail to complete recommended joint exercises. For many therapists, the only recourse is closer monitoring, with longer phone calls and more follow-up visits—all costly and only incrementally effective.

Some researchers say that the answer to this problem can found in digital Zen gardens and in the company of space-farers brandishing ray guns.

As chief executive officer of Blue Marble Game Company, Flynn is one of the leading developers of therapeutic video games—interactive "translations" of evidence-based therapy programs designed to boost adherence and, consequently, outcomes among patients. "The literature says if you do these exercises, you can reduce your fall risk," she explains. "We embed them in an interactive, user-centered design."

Thanks to high-end technology made commonplace by gaming equipment like Microsoft's Kinect camera, seniors who wish to reduce their fall risk are no longer left to rely on phone calls and slips of paper, but can project themselves into a salubrious park environment with warbling brooks and a 3-D-rendered tai chi instructor. They work through an electronic adaptation of a program that has been shown to cut a person's fall risk by 35 percent. Think Nintendo Wii, but with balance exercises rather than swordplay or shoot-outs.

In another game, the player assumes the role of an astronaut harvesting gemstones in a Martian cave while evading giant space eels. The game, which is designed to help patient groups like ADHD sufferers and victims of head trauma, is based on interventions shown to improve attention, memory and executive function. According to Flynn, it may carry particular benefits for young patients, who are typically burdened by a constant flow of new treatments and evaluations. "Some of these kids have been tested and tested and tested, and they don't want to be tested again," she explains. No kid wants to have an attention deficit—and oftentimes, the last thing they need is another reminder of their diagnosis. By blurring the line between health care and entertainment, this game helps patients without constantly bringing up their need for help.

Clinicians have been interested in the therapeutic capacity of video games since the medium's infancy, with titles likeBronkie the Bronchiasaurus (asthma management) and Packy and Marlon (juvenile diabetes care) dating back to the mid-1990s. The novelty of therapeutic gaming in 2014 may lie in its emphasis on comprehensive, full-body interaction; its striking departure from two-dimensional environments and tasks; and its capacity to invoke many of the social aspects that have come to define recent mainstream games—effortless data sharing, player-developer feedback and online communities.

Some believe that if the medium is to achieve its full therapeutic potential, developers must keep in mind yet another quality—one that doesn't readily lend itself to scientific inquiry. Marientina Gotsis, a researcher in the interactive media and games division at the University of Southern California (USC), says the key to developing an effective game intervention is to view the end product as a piece of art rather than a simple clinical utility. "When we look at a solution to a problem as pure technology, it always fails," she explains. Gotsis, who also heads the university's Creative Media & Behavioral Health Center, believes gaming has evolved to a point where even small developers have very sophisticated tools, allowing studios to create and showcase immersive experiences on a very tight budget.

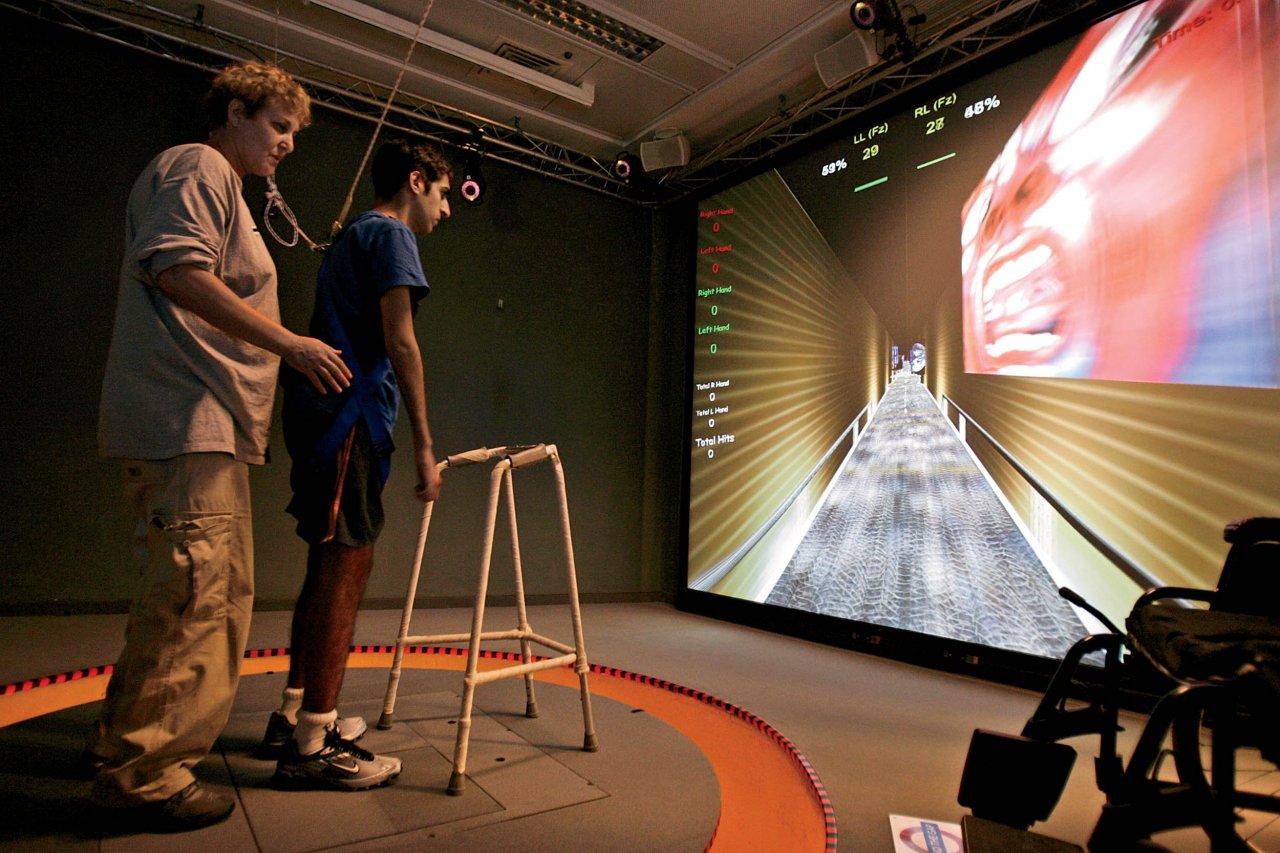

Skyfarer, a game she and her colleagues created for paraplegics, exemplifies this type of experience-driven design, with a therapeutic element that quickly dissolves in a surprisingly intriguing narrative and generous use of metaphor. At its core, the game emulates Strengthening and Optimal Movements for Painful Shoulders (STOMPS)—a home-based intervention designed to build strength and prevent shoulder injury among people in wheelchairs. But instead of performing the exercises in the living room, the patient takes the role of an ethereal figure lifted from the mythology of pre-Columbian South America. The goal is to find artifacts, assemble a flying vessel and soar high above the Andes. It all takes place in a metal rig fitted with cables, pulleys, weights and a flatscreen.

It is too early to say whether games like these will lead to a significant increase in therapy adherence across the public health landscape. Longitudinal studies evaluating that type of impact require a finalized product—and at this point, many developers are still in the tweaks-and-fixes stages. That said, both Gotsis and Flynn cite a number of published and forthcoming case studies indicating a positive response from samples.

Maryalice Jordan-Marsh, a nurse psychologist at USC who serves as an adviser for Gotsis's project, says that the most encouraging reactions have been recorded in informal showcase settings, where non-paraplegic friends and relatives of invited patients have eagerly waited their turn. "Before this approach was developed, rehabilitation exercise was the patient's own business," she explains. "This adds a whole other dimension to rehabilitation."

Regardless of whether these games will ultimately deliver on their promise to make people more inclined to follow their doctor's advice, the most recent projects raise some rather interesting points about the future of therapy as a whole. First, with more and more games emphasizing the social capacity of the medium, it stands to reason that medical intervention may soon trade its current definition for one that is much broader. In an age where therapy is screen time and screen time is mobile, the dreaded clinic quickly loses its spot as the primary point of care. Patients can interact with rehabilitation schedules on their own terms, wherever they want.

But more important, therapeutic video games also challenge the very nature of the interaction between doctor and patient. As games and other interactive delivery methods make care available outside buttoned-up offices, researchers and clinicians will soon have to admit experience and engagement as important parts of intervention design.

"If we really thought about health care as an experience design problem in addition to all the science we're trying to do, I think it would really help," Gotsis says.

Care, it seems, must become more fun.