The White House announced on Sunday that Malia Obama will attend Harvard University—but not starting this fall—and instead will take a gap year, a practice gaining momentum in the United States in recent years.

In its announcement, the White House said the president's older daughter will begin at Harvard as a member of the class of 2021, starting her freshman year in fall 2017. She will defer college for a year after graduating from Washington, D.C.'s Sidwell Friends School this spring.

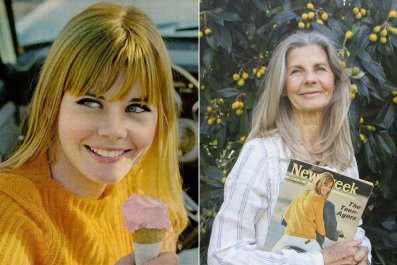

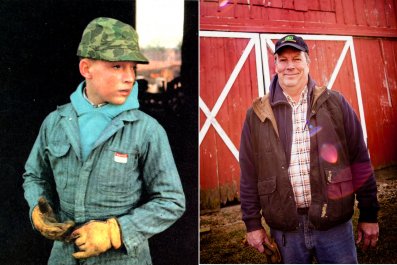

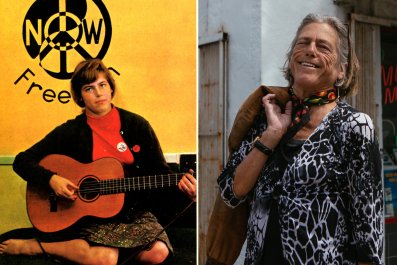

Gap years, which students typically take between high school and college in order to travel or gain work or personal experiences—though they can take place during or after college as well—were once more common abroad. Janet Hulstrand outlined the term and practice, which originated in the United Kingdom, in a 2010 article. Recently, taking such time off has becoming an increasingly popular option for young people in the U.S., and has even sprouted a new industry.

"We've seen this huge shift over the years since its inception in the '80s to present day," says Holly Bull, president of the Center for Interim Programs, which counsels students and mid-or post-career adults on gap programs. "There's far more awareness and support for the idea." When her father founded the Center in 1980, she says, "nobody was talking gap year in the U.S."

It's Britain's Prince William and Prince Harry, who took time off from their studies in the early 2000s, who deserve credit for the growing interest in gap years, according to Bull. "That was when the term gap year started to really appear in the United States," she says.

Bull expects a similar spike following Malia's news, and tells Newsweek that she already heard from one student she had counseled who "was right on the fence about it. And when she heard Malia was going to take a gap year, she said, 'OK, I'm going to take one too.'"

The American Gap Association, an accreditor of gap year programs, estimates that 30,000 to 40,000 students in the U.S. take such time off annually, whether for a semester or longer. Gap year enrollment grew about 23 percent between the school years starting in 2013 and 2014 and has grown every school year since 2006 or earlier. Attendance at gap year fairs has spiked 294 percent since 2010, the Association says.

The Association happened to be hosting its annual gap year industry fair in Boston on Monday. "There's certainly excitement in this room that this is the choice that Malia has taken," says Jane Sarouhan, an association board member and vice president of the Center for Interim Programs.

Experts on gap years say the uptick may be related to an increasingly stressful college admissions process. "You're looking at a growing rate of student burn-outs," Sarouhan says, "so there's definitely a link to the intensity of the college application process." Today's young people also are often talented in many ways, "but don't have some basic soft skills" such as "how to take care of themselves, how to make good choices, how to get themselves out of bed, accountability," and may seek time away from academics to acquire those, she says.

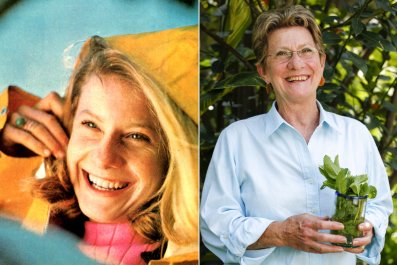

According to a survey of gap year students, 92 percent said they chose time off for reasons related to personal growth. Another 85 percent say they wanted to travel and experience other cultures, and 82 percent said they were doing so in order to take a break from academics. The numbers do not add to 100 percent, as students may have cited multiple reasons.

A number of formal gap year programs exist. The Association has accredited at least a dozen that operate activities such as environmental conservation, wilderness education, teaching, volunteer work and cultural immersion. Bull says a student will often spend part of his or her year off in a structured program, and the other part in more "independent placements."

"You need to put some work into a gap year because you don't want to be twiddling your thumbs at home without enough to do and your friends are off at college," she says.

Researchers have found that the grades of students who took gap years improved more than those of students who didn't, and that gap year students in the U.S. and U.K. were more likely to have higher grade point averages upon graduation than similar students who did not take time off. More than half of gap year students in a survey said their experiences set them on a career path or solidified their choice of academic major.

Given such findings, schools have grown more receptive toward students who wish to defer for a period of time. Harvard encourages students to take time off, and Princeton, Tufts and other schools offer their own gap programs. Florida State University recently announced it would offer incoming freshmen financial assistance toward such programs. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill offers similar financial aid.

"Just about everybody allows it, because just about everybody realizes that it ends up resulting in more mature, more focused student bodies," says Bob Clagett, director of college counseling at St. Stephen's Episcopal School in Austin, and the former dean of admissions at Middlebury College, who has studied the gap year trend.

Despite the momentum, many families worry about how expensive such programs may be, gap year experts say.

"There's a very common misperception," Clagett says, "that the gap year phenomenon is primarily the domain of the wealthy, or at least the affluent, and I think it's really important for people to understand that anyone can do a gap year." He worries that Malia's decision will deepen that misperception. Some students who work during such a year can even make money, he adds.

Still, the most expensive programs could run as high as $40,000, says Sarouhan. Clagett notes that deferring a year might also result in having to pay a higher tuition fee as rates increase.

Harvard says that typically 80 to 110 of its incoming students defer before starting studies there each year, which is twice the number that the school said deferred four years ago, The Washington Post reports. Last spring, Harvard admitted 2,080 students.

For the child of a U.S. president, delaying until her dad leaves office has added bonuses. Starting Harvard next fall instead of this one means that Malia will not be the daughter of a sitting president while on campus. The Post reports she may have less security with her for that reason.

"I think it makes a lot of sense for her," says Bull, who adds that she has counseled a well-known television actor. During a year off "you're probably going to be somewhat in the public eye but not quite in the same way, and then she'll start at college when there's not so much spotlight on her."

Citing an unnamed source, the Post said Malia has not yet decided how she will spend her gap year before Harvard—a school both of her parents attended.

Meanwhile, Harvard awaits her arrival. Writing about Malia and her year-off announcement, a student quipped in the school newspaper, "I guess that means one less year of our friendship."