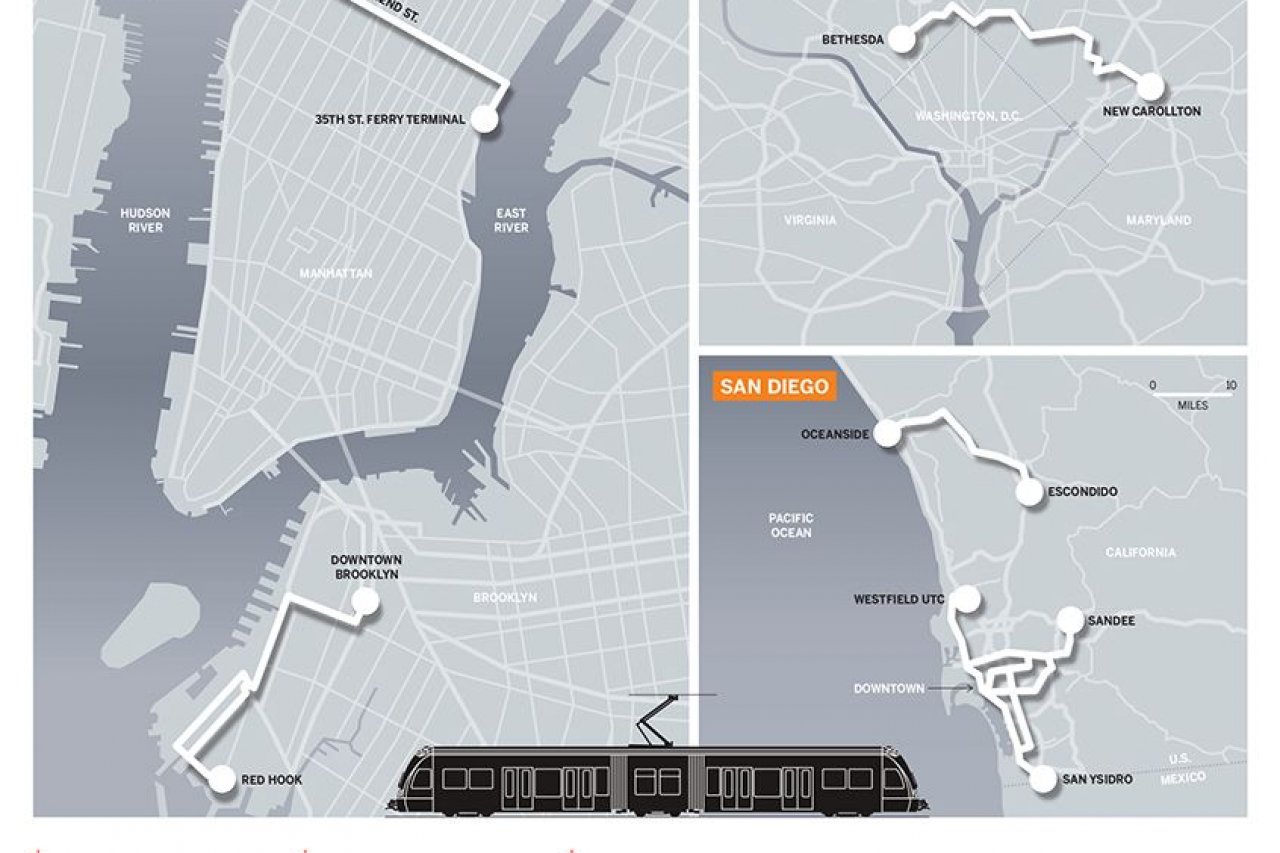

In 1995, a nonprofit transit advocacy group in New York, the Brooklyn Historic Railway Association (BHRA), decided to construct a light rail service connecting the underserviced neighborhood of Red Hook to downtown Brooklyn. After obtaining permission and funding through the city in 2000, the group laid down a half-mile of track. But a few years later, in 2003, New York City's Department of Transportation revoked the group's construction permit and ripped up its tracks without providing the BHRA with any explanation.

The next year, however, the city received almost $300,000 in federal money—more than it had invested in the BHRA's trolley—to study whether it was feasible to build essentially the same line. It sat on the money for years before eventually spending only a small portion of it to conclude such a project would be too expensive. Proponents of the Red Hook trolley were confused and angry. "There is an unquantifiable resistance to electric-powered street transit in New York," says Ray Howell, a BHRA member.

It's not just New York. Despite the environmental benefits of mass transportation—which saves 37 million metric tons of carbon and 4.2 billion gallons of gasoline each year (about 3 percent of total U.S. motor gasoline consumption)—this resistance exists in cities pursuing light rail projects across the country.

Take Arlington, Virginia. In 2004, it, like many U.S. cities, was growing. In the previous five years, it had grown 15 percent. To many city officials, that seemed like a sign that it was a good time to invest in a streetcar, which would reduce traffic congestion and promote the development of local businesses. But after the county outlined a plan in 2006, the local green party railed against the idea, characterizing it as a "minority removal" project that would spur gentrification. Townspeople, meanwhile, complained that the plan was "environmentally regressive." Since then, the project has languished and has become, in the words of County Treasurer Frank O'Leary, "a political nightmare in Arlington."

In nearby Maryland, a similar debate is still raging over whether the state's D.C. suburbs should build a Bethesda-to-New Carrollton light rail line that links up with the existing Washington Metro System. Fights are ongoing in parts of Minneapolis, San Diego and Northern California as well. "The environmental benefits of rail are pretty well demonstrated," says Deron Lovaas, the federal transportation policy director for the Natural Resources Defense Council. Yet the United States has built only 30 light rail systems; Europe, with twice the population, has about 200.

Why have so many light rail projects failed in the U.S.? "It's a combination of history, greed, politics and sprawl," says Duncan McFetridge, chairman of Save Our Forest and Ranchlands, who has been fighting for years to build a light rail line in San Diego.

That history began after World War I, explains Ben Ross, a Washington, D.C.–area transit activist and author of Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism. In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Euclid, Ohio, could put land use restrictions such as building height limits on private property. In his majority opinion, Justice George Sutherland cautioned against the "evils of overcrowding." This distaste for apartment buildings was codified in the 1940s and 1950s as suburbanites continued to establish regulations that limited the population density of suburban areas, essentially blocking any form of urbanization.

"The ideal environment for a light rail is a corridor lined with apartment buildings and houses," Ross says. "But zoning is really preventing those kinds of corridors." In Minnesota, residents are debating a planned 15-mile light rail line connecting downtown Minneapolis to Eden Prairie. To complete the project, the city has adopted a policy of "transit-oriented development" that will relax zoning restrictions to permit the creation of denser, mixed-use communities around transit lines. In response to this policy, one resident, a fellow at the Center of the American Experiment in Minneapolis, wrote a Wall Street Journal opinion piece cautioning readers that "Orwellian appeals to 'equity' and 'sustainability' are a serious threat to their democratic traditions of individual liberty and self-government."

Compared with Europeans, Ross says, "Americans have much greater interest in sorting out different people of different incomes into different neighborhoods." When it comes to mass transit, he says, "the classic argument is that it's gonna bring crime. The fashionable one right now is that it will gentrify our neighborhood and make poor people suffer. I've seen people make both of these arguments in the same paragraph."

City residents can't decide whether light rail will make good neighborhoods bad, or bad neighborhoods good. But either way, they don't want it to happen.

In the case of the light rail project in the D.C. area, which Ross has spent 20 years fighting for, one of the main sources of opposition was a country club whose golf course would be bisected by the line. In 2008, a clubhouse board member told The Washington Post the club was "not anti-transit" but simply "has questions about spending $2 billion of taxpayers' money at a time when the state is arguably in financial distress." After five years of fighting, however, the club backed off on its fiscal responsibility argument, signing a legal agreement not to oppose the line—provided it was moved so as not to obstruct the view from the clubhouse.

The gentrification brought by rails, Ross says, is a "real issue—but it's a real issue because we have so few places served by good transit." Millennials are increasingly drawn to homes and apartments near rail lines. Today, 70 percent of millennials take some form of public transportation each week, and only 54 percent of eligible people under 18 get a driver's license. "It's not just millennials," says American Public Transportation Association President Michael Melaniphy. "It's the baby boomers too," who, upon retiring, have begun discarding their cars in exchange for city life.

For mass transit advocates, the problem of zoning restrictions is compounded by the fact that few politicians see any incentive to change them. Transportation departments hold fast to America's highway allegiance, forged in the middle of the 20th century. In one telling example from that time, New York City power broker Robert Moses allegedly viewed mass transit so negatively that he built tunnels too low to accommodate public buses.

Moses believed all traffic problems could be solved by more roads. Many officials, says D.C. Councilman and mass transit advocate Tommy Wells, still operate under the belief that traffic congestion can be relieved by building more lanes to a highway. In reality, he adds, "it just expands the parking lot."

The federal government began taking steps toward mass transit in 1991, when it passed the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act, allowing state departments of transportation to use money earmarked for highways on public transit projects. But such projects have failed to materialize—mostly because those in charge don't want them to. "Those 50 years and older—often those in power in a city—are still wedded to cars," says Wells. Part of the reason for that allegiance, Ross says, is that "there's lots of contractors and highway bureaucracy." Highway projects have long provided lucrative construction projects to local contractors. Getting mass transportation built is far less streamlined. Or lucrative.

"Welcome to the world of transit" is a common refrain among light rail advocates all too familiar with the odd political decisions in the transportation world.

Roxanne Warren is the co-chair of the New York nonprofit Vision 42, which is working for a light rail line connecting the east and west ends of Manhattan along 42nd Street. Her experience trying to get the trolley system built, she says, shows how private development can thwart transit projects. "We went to City Hall," she says, "and we were told, 'Whatever you do, don't try to compete with the No. 7 subway extension.'"

It was a curious stipulation; the projects are hardly related. The No. 7 extension, which is still unfinished, lengthens the subway by only one mile, where it connects to the Hudson Yards development, a massive private project on the far west (and less developed) side of the city that has received some $328 million in tax breaks from local government. "It's two different kinds of transportation," says Warren. "One is underground and high-speed. The light rail would be at grade and low-speed. It's generally agreed that the city is lacking crosstown rail service. Whereas the light rail would go river to river [14 blocks], the No. 7 would only go from Times Square to 11th Avenue and 33rd Street [four blocks]. It was solely for the purpose of building the Hudson Yards."

There are plenty of reasons New York and other cities should be embracing light rail projects. Not only does mass transportation reduce traffic and motor vehicle pollution; it also increases the property value of homes and businesses. On top of that, it makes them more resilient to hard economic times. After the 2008 recession, the American Public Transportation Association found that homes located within a half-mile of a public transit station lost, on average, 42 percent less of their value.

"It's a mystery," says McFetridge on why San Diego won't build a light rail system. "How do you explain it against every possible reason?"

SEE THE LISTS: Top 10 Green Companies in the World | Top 10 Green Companies in the U.S | Full World Rankings | Full U.S. Rankings

Our Green Rankings Section