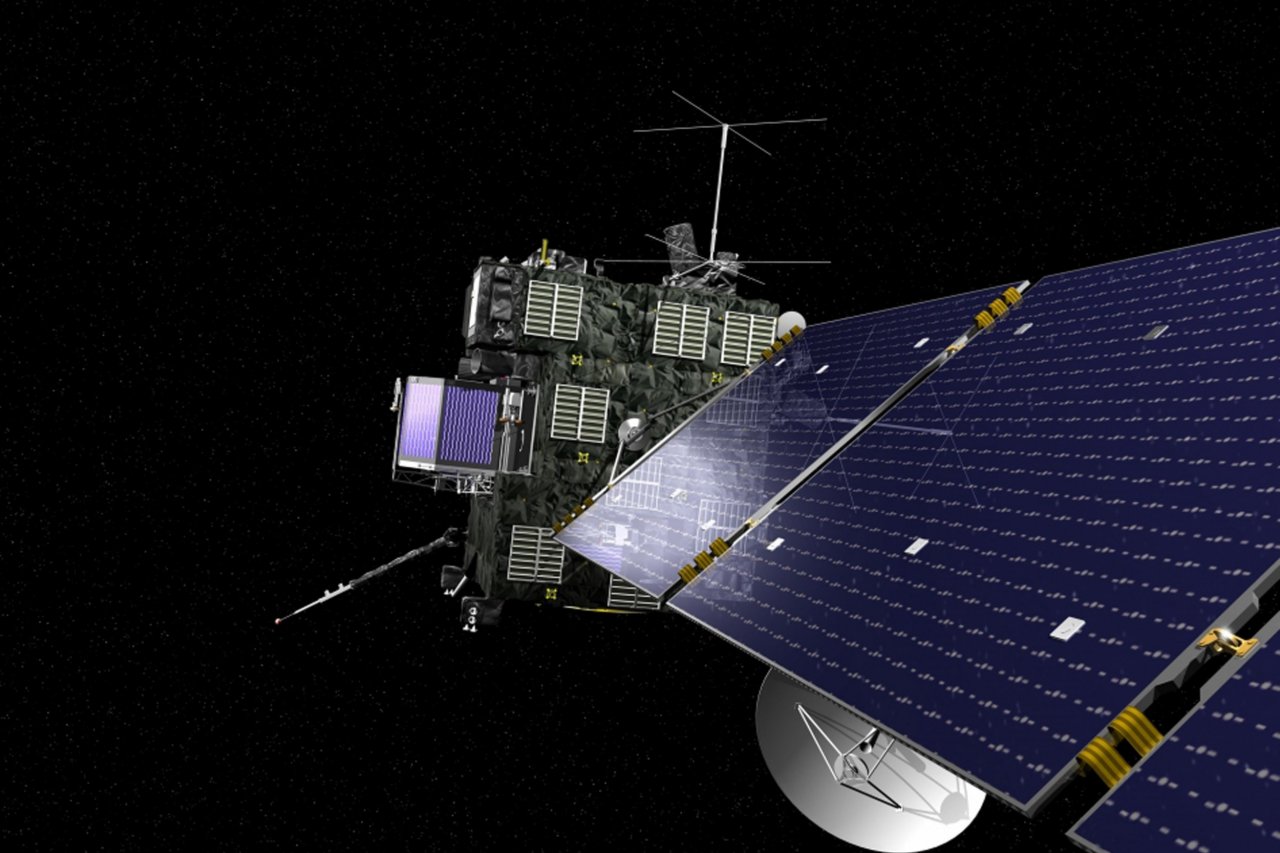

The three-ton probe with huge wing-like solar panels is named Rosetta because, like the stone that gave insights into ancient Egyptian writing, the mission will reveal much about the birth of the solar system 4.6 billion years ago, as Earth and the other planets coalesced into being from a vast cloud of dust that swirled around the infant Sun.

In May, Rosetta carried out the first of a series of major burns of its rocket thrusters to close in on its target, a comet with the inelegant name of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which follows an egg-shaped orbit around the Sun, swinging from beyond the orbit of Jupiter, nearly 500 million miles away, then passing between Earth and Mars.

The billion-dollar mission began in March 2004, when Rosetta was lofted into the tropical skies of Kourou, French Guiana. The successful launch came as a relief to both the European Space Agency (ESA) and to Arianespace, manufacturer of the Ariane 5 rocket that had failed in four of its 18 earlier launches.

Rosetta's journey has seen it fly past asteroids, slingshot around Earth three times, and once around Mars. In June 2011, far out in the solar system, a lack of solar power to run the spacecraft safely meant that most of its systems had to be shut down.

Then, when the probe swung back towards the Sun in January this year, there was a tense moment when the probe roused itself after two-and-a-half years of hibernation. The team had to wait much longer than expected, as a mystery glitch forced its onboard computer to reboot a second time. "The delay was only 18 minutes but it felt much longer," said professor Mark McCaughrean, ESA's Senior Science Advisor. "Some people were close to expiring."

Before Rosetta could phone home, automated commands stopped the spacecraft spinning, warmed up the craft's components, and pointed its antenna back at Earth. It was forced to use its spare star tracker: the main one was still frozen. Mission control only relaxed when they picked up its carrier signal, prompting a tweet of the classic computer greeting, "Hello world!"

Images taken by Rosetta between March 24th and May 4th show the comet emitting a halo of dust and gas as it approaches the sun, which heats the frozen surface to make gases spout. Jets emerge from the heart of the comet, expanding in a ball to make it look much larger – the so-called coma was revealed to stretch 800 miles into space. The pictures also helped the Rosetta team work out that the comet completes a full turn every 12.4 hours, about 20 minutes less than previously thought.

Last month the probe was within 600,000 miles of its target. Then came another nervous moment: the first major braking maneuver. The reason for the tension dates back to a few years ago, when a leak was spotted in Rosetta's propulsion system. Though the engineers had devised a way to work around the leak, it had not been tested in action before. Four of its small thrusters had to fire for seven and a half hours to cut the relative speed of the comet hunter. "That was critical and, fortunately, it worked perfectly," says McCaughrean. "However, there are still two more big braking manoeuvres to go.'"

In August, Rosetta will only be four miles from its target and will slowly work its way closer. There it will map the comet's surface, gravity, shape and rotation to find a suitable spot to dispatch the metre-cubed Philae lander in November while skimming over the comet at a height of just two kilometres.

The timing comes before the comet – already spewing a mist of gas and dust – gets too close to the Sun, when it will start to spout more debris. However, unlike an earlier comet probe (ESA's Giotto probe) that was blinded during its close encounter with Comet Halley in 1986, Rosetta will be far less prone to damage because it will travel at a small relative speed of only a few metres per second.

Philae will descend into a tiny target zone, unguided and without intervention from Earth due to a 30-minute delay in communications. The operation will be risky and, in the worst case, Philae could end up tipping over on a rock or falling into a crevice. "We believe that risk is worth taking to make the first ever soft-landing on a comet. But even if the lander is lost, the orbiter will still be there to do the lion's share of the science," says McCaughrean. Philae will "harpoon" the comet to hold itself down under the very weak gravity. Once Philae has secured itself on the surface, its batteries will last a few days; then it must survive on solar power, and that will then dwindle as its panels become coated with dust.

Together, Rosetta and Philae will provide a revealing glimpse back in time, since the gas, dust and organic molecules in the solar system's comets are relatively unchanged since their birth along with the solar system. Comets are not only thought to have delivered a large fraction of Earth's water but even amino acids, the building blocks of life, though this is still controversial.

Rosetta will circle the comet at the equivalent of walking pace, using cameras and sensors to gaze down in detail, while spectrometers analyse the chemistry of dust, gas, and plasma flowing away from the surface. Meanwhile, Philae will study the comet's surface structure and make-up.

Both will weigh up the isotopic composition of comet ice – the ratio of normal and heavy hydrogen (deuterium) to see if it matches Earth's water signature. Philae will even be able to reach about 10 inches beneath the comet's surface, which may harbour organic materials, and study the chirality (or "handedness") of any detected amino acids, the building blocks of proteins found in all life. On our home world, amino acids are all left-handed, so finding a predominance of left-handed molecules on the comet would add weight to theories that such a cosmic wanderer seeded life on Earth.

Last November, just as it was sweeping past the sun, Comet ISON disintegrated before the gaze of a flotilla of spacecraft and ground-based telescopes, giving more data on these primordial objects. The passing of ISON provided a valuable dry run for this October, when Comet Siding Spring is due to pass by Mars, enveloping it in its shroud of ice and dust. And to top it all off, there's Rosetta's mission: this is indeed the year of the comet.