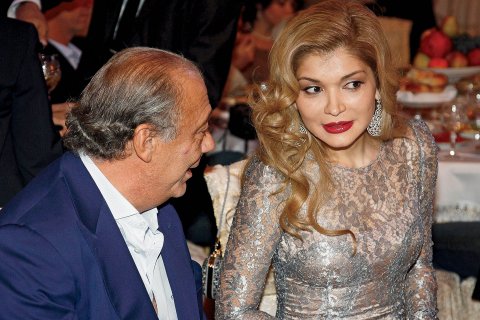

Right up until her father ordered her arrest, Gulnara Karimova lived a charmed life. Under the stage name GooGoosha, she was Uzbekistan's most famous pop star, performing "Bésame Mucho" with Julio Iglesias.

She signed Gerard Depardieu for a film she'd scripted. (It was never made.) She debuted a fashion line in New York in 2012. She designed jewelry for Chopard and perfumes—Victorious for men and Mysterieuse for women.

Karimova was also a diplomat and an academic, serving as ambassador to Madrid and the U.N. in Geneva and as professor of political science at University of World Economy and Diplomacy in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Her business interests in telecoms, entertainment and transportation made her the wealthiest woman in Uzbekistan.

But more important than all this, she enjoyed the love and patronage of her father—Islam Karimov, the Soviet apparatchik turned despot who has ruled Uzbekistan as a personal fiefdom since 1989. "The president trusted Gulnara," says Ismat Hushev, a newspaper editor who was close to the Karimovs in the 1990s. "He thought she could perhaps succeed him."

As long as she enjoyed her father's protection, Karimova was untouchable. But even her friends admit she tested her father to the limits. Karimova "remains the single most hated person in the country," the U.S. State Department reported to Washington in 2005. Ordinary Uzbeks saw her as "a greedy, power-hungry individual who uses her father to crush business people or anyone else who stands in her way."

She antagonized foreign investors and stole businesses with impunity, according to documents published by Wikileaks. She rode roughshod over Uzbekistan's top officials—including the heads of the country's security services. Friends who fled into exile accused her of snorting cocaine and dabbling in black magic.

Karimov's patience came to an end at dawn on February 17 of this year. "Ten SUVs with military in full gear—like for capturing terrorists—took over the [neighborhood] from both sides," according to Karimova's own account. Armed heavies surrounded her mansion in Tashkent and 41-year-old Karimova, her 15-year-old daughter and her boyfriend, Rustam Madumarov, were arrested. She claims Muijon Tokhiriy—head of the President's Security Services—roughed her up.

Ever since, Karimova has been under house arrest. A single, smuggled-out photo shows her disheveled and without makeup, sitting on an unmade bed drinking from a carton of chocolate milk.

Within hours of the raid, she was a nonperson. GooGoosha's music videos disappeared from state television. Her younger sister, Lola Karimova-Tillyaeva, 35, claimed on the BBC's Uzbek service she had not been in touch with Karimova for 12 years.

Karimova's captors cut her off from Twitter, on which she used to post fur- and tiara-clad selfies interspersed with corruption accusations against Uzbek officials. The only word from her came in handwritten letters smuggled out by visitors. Even in the original Russian—Karimova speaks little Uzbek, like many children of elite Soviet families—the letters make for bizarre reading.

"The blood of my wounds does not clot any more, it's everywhere. Its taste is of salt, and its smell is sharp. Why? Why … ?" Karimova wrote in a letter posted on an opposition website.

Why would Karimov abandon the daughter he had indulged for so long? Her explanation is that her father has gone crazy. "When God wants to punish a human he takes away his mind," she wrote. "Otherwise no one stoops so low as to harass their own child, and the child of their child."

Former associates have a different theory: "She stole too much from too many people," says one Uzbek-Afghan businessman whose business was taken over by Karimova's associates five years ago, forcing him to flee the country. He believes Tokhiriy and Rustam Inoyatov, chief of the National Security Service, forced Karimov to rein her in.

"The woman became unstoppable," says Shahida Tulaganova, an Uzbek journalist. "She was undermining her father, making public accusations against her mother and sister.… They had to silence her."

Even Karimov's friends concede the torrent of stories about Karimova's crooked business practices are largely true. Hushev believes it was Karimov himself who ordered her arrest: "He was shown documents which showed that she was no longer worthy of his trust."

Foreigners who have had dealings with Karimov say it's unlikely the old man's control has slipped. Karimov "has always maintained a fine balance of power between his country's rival security services," says one senior Western diplomat who served in Uzbekistan. "The idea of [Karimov] being outmaneuvered by his own security chiefs doesn't make much sense."

Either way, the beginnings of Karimova's rise—and the seeds of her fall—can be traced to her return to Tashkent in 2001 after a 10-year marriage to a U.S. citizen of Uzbek-Afghan origin. She'd spent most of the previous decade in the U.S., earning a master's in political science from Harvard and having two children.

But after her marriage fell apart Karimova returned to Uzbekistan "determined to become her own woman" according to Tulaganova. "She wanted to be a strong woman. She is ambitious, but has serious selfhood issues. She has a lot of anger."

Karimova's first act after returning to Uzbekistan was vindictive. She used Uzbekistan's security forces to confiscate her ex-husband's businesses—including a Coca-Cola bottling franchise—and had his relatives imprisoned then expelled from the country. "Before, [Karimova's in-laws] were treated like royalty," says one former business associate of her first husband. "Then came the divorce, and suddenly everyone said, 'Who were those people?'"

She also indulged her teenage fantasies of show business stardom, backed by her father's money, transforming herself into GooGoosha—her father's baby name for her. She was appointed Uzbekistan's deputy foreign minister for cultural affairs. People began to talk of her as Karimov's successor.

She also went into business. According to the Uzbek-Afghan businessman, "People from the [National Security Service] came to my office. They proposed that we take on a new partner in our business.… At first I hoped it was simply their private way of extorting money. But this was coming from the very top." His company was absorbed into one controlled by a Karimova associate.

U.S. Embassy cables tell a similar story—in 2009 an American businessmen complained that after his company turned down Karimova's offer to buy into the Skytel mobile telecommunications firm, "the company's frequency [was] jammed by an Uzbek government agency."

"She was a predator," says Kamoliddin Rabbimov, who used to work in Uzbekistan's presidential administration before fleeing in 2007 to Paris. "She stole all the profitable businesses in Uzbekistan." Victims included foreign-owned firms such as Newmont Mining, Oxus Gold, Spentex and the MTS Uzbekistan cellphone network. All were subjected to criminal investigation by Uzbekistan's tax police and were either shut down or had their assets seized or were bought at less than their market value.

Karimova's problems began when MTS—a Moscow-based cellphone provider—fought back. MTS subsidiary MTS Uzbekistan went bankrupt in January 2013 after accusations of tax fraud, the arrest of employees and the expulsion of some Russian executives. Protesting its innocence, MTS went public with counter-accusations that it had been victim of a shakedown.

They agreed to share information with Swiss authorities, who had launched an investigation into another Karimova-linked company: Zeromax. The Swiss-registered holding company was founded by Uzbek businessman Gafur Rakhimov, described by the U.S. Embassy as a "local organized crime boss." In court documents, Swiss prosecutors accuse Karimova of cooperating in "creating corrupt business mechanisms" and "money laundering."

Zeromax became, prosecutors allege, a vehicle for Karimova to receive bribes from businesses wanting to enter the Uzbek market. The biggest was $340 million allegedly paid by the Swedish telecommunications company TeliaSonera in 2007 to obtain an Uzbek 3G license. According to the Swiss prosecutor general, about $912 million of Karimova's assets have been frozen in Swiss bank accounts—the largest sum ever frozen in a Swiss criminal investigation. "I never met TeliaSonera representatives," Karimova told Uznews in April when asked about the allegations.

Some of Karimova's safety deposit boxes, filled with jewelry and artworks valued at tens of millions of Swiss francs, were also seized. Money laundering probes have also been launched into Karimova-related companies in France, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

Craig Murray, British ambassador to Uzbekistan from 2002 to 2004, alleges that the Karimov family "looted Uzbekistan's large state-owned gold industry by stealing physical gold, some of which is fenced through Karimova's jewelry business, but most of which is stored as collateral" in "large underground concrete vaults established under the rear of the garden behind Gulnara's [Geneva] house."

Murray alleges that Karimova is guilty of far worse crimes than theft. "She has had business rivals killed," Murray writes in a controversial blog. "She has been involved in trafficking girls into prostitution in Dubai, a partner in the narcotics trade and she benefits financially from the open forced labor of millions of small children picking cotton in the state farms."

Murray was dismissed from his ambassadorship in October 2004 after allegations of abusing his position, including granting U.K. visas in exchange for sex. Murray claims his exposure of Uzbek human rights abuses was embarrassing to the British government. The Uzbek president's press office did not respond to Newsweek's inquiries about Karimova, saying it was "an internal family matter."

There are signs Karimova and her father could be reaching an understanding. Her Twitter account came to life again in April with some retweets of supporters' messages—but, for the moment, no selfies. "She has gone from being the most hated person in Uzbekistan to being a victim of the regime," says Rabbimov. The world's most dysfunctional ruling family could be close to a deal—Karimova stays silent and lies low, and "reinvents herself as a human rights defender," says Tulaganova.

Karimova's house arrest could be her father's final, and most intelligent, service to a beloved wayward daughter. Karimov is 76 years old and, while Karimova's reputation is far too tarnished for her to be considered as his successor, by publicly punishing her, Karimov has increased her chances of surviving into the next reign with her freedom and some of her fortune intact.