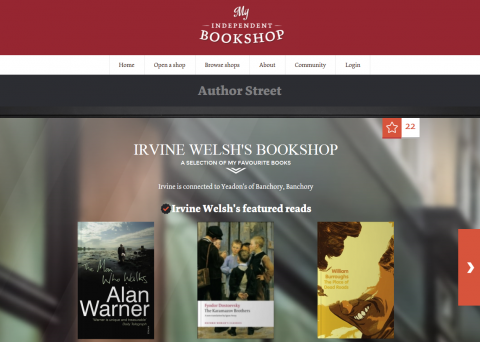

For the window of his bookstore, Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh has chosen Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov and William Burroughs's The Place of Dead Roads. Fantasy novelist Terry Pratchett's shop, Narrativia, is displaying Neil Gaiman's American Gods and Lynne Truss's ode to punctuation, Eats, Shoots and Leaves. A few doors down, Tony Parsons, author of the British best-seller Man and Boy, has shelves stacked with titles by John le Carré and Mario Puzo. Welcome to the newest address in bookselling: Author Street.

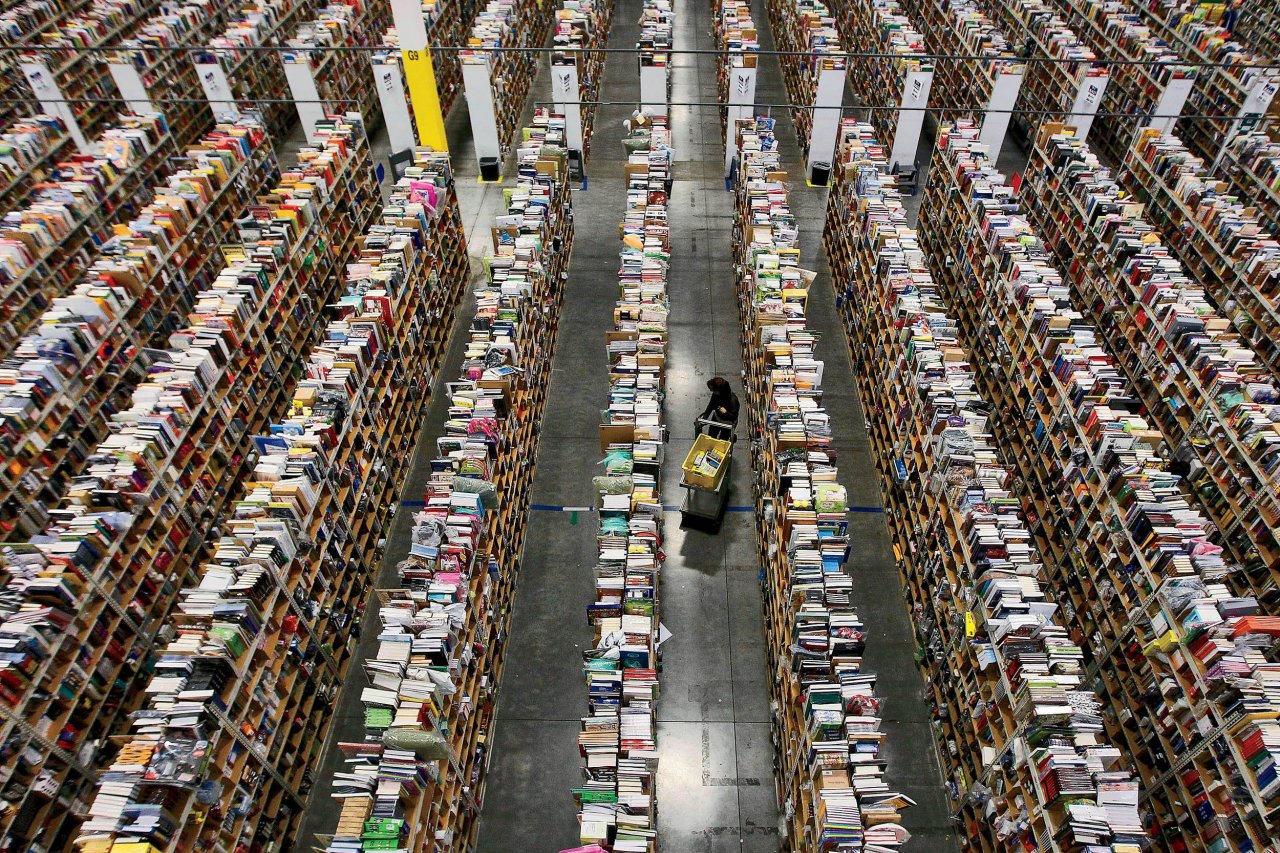

None of these shops have a physical existence: They are part of a recently launched British website, myindependentbookshop.co.uk, where anyone can post a selection of books he or she loves. If a reader buys a book you recommend, a percentage of the price goes to your favorite brick-and-mortar bookshop. Penguin Random House, which created the website, denies that it is trying to compete with Amazon, but to those who hate Amazon's Godzilla-like dominance of the market, myindependentbookshop.co.uk is a heartening salvo in the battle between the Seattle-based bookselling behemoth and traditional booksellers (to say nothing of Amazon's current pricing war with the Hachette Book Group).

"I love the idea of this website," says Felicity Rubinstein, co-owner of the bookshop and literary agency Lutyens & Rubinstein in London's Notting Hill district, "because what they've identified is that Amazon and its algorithms aren't personal, and the beauty of an independent bookstore is that it provides you with recommendations from people you trust."

With fewer than 1,000 independent bookshops left in the U.K. (compared with almost 11,000 in the U.S.), the success of Lutyens & Rubinstein—which opened five years ago, when the future looked blacker than printers' ink—seems almost miraculous. But take a trip to Chelsea, London, and you will find something stranger still. Tucked away off the King's Road, John Sandoe (Books) Ltd. (established in 1957, and with a customer list including Sir Tom Stoppard and Sir Elton John) has just expanded, increasing its floor space by a third.

"We had a chance to acquire the next-door premises," explains the shop's co-owner, Johnny de Falbe, "and it certainly didn't seem an irrational thing to do. To say no would have felt awful—really like turning up one's toes."

According to de Falbe, the disappearance of hundreds of independent bookshops has increased people's appreciation of the ones that still survive. "We may have lost some customers, but overall we've gained in trade, precisely because of Amazon. The feel of the physical space, and the idea of a bookshop as a nice place to go, matters to people more than ever, and they will make a considerable effort to come here, both from this country and from abroad."

The main danger to shops like his, he says, is the notion that they are doomed, which threatens to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. "Of course bookshops are under strain—from Amazon and high rents and rates. But the number of people who come in and say, 'I didn't think shops like this still existed' is absolutely startling. They don't even look for a bookshop—they just go online."

It was to counter this mindset that Britain's Booksellers Association and the Publishers Association launched the Books Are My Bag campaign last autumn. Devised by international advertising agency M&C Saatchi and embracing bookshop chains as well as independents, the campaign used photographs of celebrities—such as actors Bill Nighy and Damian Lewis (Homeland) and celebrity chef Jamie Oliver—carrying bags stamped with the campaign slogan.

Sympathetic celebrities and respected authors are investing in bookshops. Model Lily Cole has become a backer of Claire de Rouen, a specialist in art and photography books in London's West End, while in the U.S. novelist Ann Patchett received nationwide publicity when she opened her Parnassus Books in Nashville, Tennessee. "Amazon doesn't get to make all the decisions," she declares. "The people can make them, by choosing how and where they spend their money. If what a bookstore offers matters to you, then shop at a bookstore."

In some countries, bookshops enjoy government protection: France's policy of "bibliodiversity" limits how much books can be discounted, while in Germany books can be sold only at the price set by the publishers. Rubinstein insists, however, that a bookshop such as hers must not be seen as "an adorable, outdated thing that needs charity. People have to think of us as a better alternative which is vital for the publishing industry."

Because Amazon and the large chains are so focused on blockbusters, she adds, "it will be harder and harder for certain kinds of books to be published if independents disappear. There will be no platform for something like the middle years of Hilary Mantel, which in turn means no Wolf Hall." Rubinstein is not entirely critical of Amazon. "To have any book that's ever been published delivered the next day is absolutely incredible. But what Amazon can't do is grow little shoots of grass. There needs to be a germinating nursery, which is what independent bookshops are."

Her reservation about myindependentbookshop.co.uk is that "it highlights the beauty of one-click [shopping]." Lutyens & Rubinstein prefers to engage directly with the public by organizing authors' talks in its shop and selling books at events, such as 5x15 (in which five authors as diverse as A.S. Byatt and Chuck Palahniuk speak for 15 minutes each). Diversification has also worked well for Lutyens & Rubinstein. "We sell lovely reading glasses from Paris and painted books by an American artist, and we've designed our own cups and saucers with the first line of a famous novel on them," Rubinstein says.

"Independents have to concentrate on what they can do differently from everyone else that's selling books, and also trust their customers," she continues. "People aren't stupid: They can see that if you love books and like coming to this shop, you have to support it, and it's worth paying a bit more—like buying meat from the butcher down the road who can tell you where the cow grazed."