On May 11, two research papers splashed like splintering icebergs on a public already worried about sea-level rise with this grim news: West Antarctica is melting out of control. Miami and Manhattan will drown sooner than we thought, the researchers claimed, and one of the authors, a NASA scientist, apocalyptically remarked that the situation "has passed the point of no return."

A few days later, in Fort Pierre, South Dakota, Terence J. Hughes still had not read either paper. Hughes, a semiretired glaciologist, had been predicting the collapse of West Antarctica since 1973, and he predicted exactly how it would collapse a few years after that—all with virtually no data. Decades passed before scientists were able to gather the evidence that would prove him right. For this prediction and others, his peers have dubbed him "a genius" and the "conscience of the glaciology community." And there are many who have a more pungent name for him: They call him a crank.

Hughes, now 76, accuses most other climate scientists of "scare tactics" and believes global warming and sea-level rise are good for us. ("Seven inches in 150 years isn't that bad!") As the world learned that the most dire sea-level rise predictions—three more feet by 2100—would probably come true, the man who foretold it shrugged.

The Eternal Dissenter

"Terry is kind of an iconoclast—one of those people that people just roll their eyes at," says Donald D. Blankenship, an ice sheet scientist at the University of Texas. "But he's also a brilliant iconoclast."

Hughes's predictive powers are legendary. "He called it on Jakobshavns, and he called it on Pine Island and Thwaites," says University of Washington researcher Ian Joughin, referring to three infamously melting glaciers.

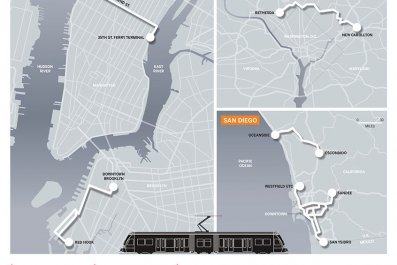

Joughin is the lead author of a paper in Science, one of the two published May 11. In it, he used complex computer modeling to predict the demise of Thwaites Glacier, the fragile pin of the West Antarctic grenade. Once Thwaites melts past a key point, it will unlock another 10 feet of sea-level rise in relatively short order, perhaps within a millennium. In the concurrent paper in Geophysical Research Letters, a team led by NASA's Eric Rignot came to the same conclusions based on direct observations. The studies combine to foretell a future where heavily populated coastal areas like New Orleans, Tampa Bay and the New York City metro area will end up partially underwater.

Nearly 40 years before them, Hughes, a young glaciologist at the time, stood eyeing the contours of a new map of Antarctica hanging on a wall at Ohio State University, where he was a research scientist. Based on a keen observation of the topography, he pointed to the area around Thwaites Glacier and told a colleague, "There's where the West Antarctic ice is going to collapse next." In 1981, he published "The Weak Underbelly of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet," a nod to Winston Churchill's World War II reference to the "soft underbelly of Europe." The Italian peninsula was vulnerable to the Allies; West Antarctica was vulnerable to warm water.

For all his prescience, Hughes can be stubbornly aloof. "My opinions in the scientific community have always been dissenting," he tells Newsweek. He says scientists and politicians exaggerate the downside of climate change and ignore its advantages. Carbon dioxide is good for plants. Thawed permafrost would make excellent farmland. And rebuilding coastal cities would create jobs. "It would be as big a boon as World War II was at getting us out of the Depression," he says.

Most of the scientific community recognizes the disruptions of climate change. Today, if any two scientists disagree about it, they're probably quibbling over specifics: about how soon its effects—rising seas, water and food scarcity, wildfires, extreme weather—will consume us. This is all "orchestrated scare tactics" to Hughes. He claims no affiliation with or sympathy for climate change denial groups, yet despises Al Gore and climate hysteria. "Too much research money to too many scientists that depend on pounding these panic drums."

Hughes is the kind of scientist no one wants to listen to but we can't afford to ignore. In a newspaper profile in theBangor Daily News from 2002, the geology department chair at the University of Maine (where Hughes worked at the time) told the reporter that Hughes can spew 100 ideas a week. Ninety-nine are garbage. "But that one is golden," he says.

The Weak Underbelly

Earth has two ice sheets: Greenland and Antarctica. Antarctica, which is the older and much larger of the two, is split into unequal halves by a long mountain range. The smaller side is West Antarctica, where solid ice more than two miles thick rests on continental bedrock well below sea level.

Snow that falls onto the ice doesn't melt; it just grows. The layers pack together and form new ice in a continent-sized pile called the ice dome. All of this ice, of course, is heavy. It's so heavy that it flows and flattens under its own weight along creeping rivers of ice called glaciers.

When a glacier flows into the ocean, it floats out across the water like a shelf. In fact, scientists call it an "ice shelf," the tip of which continually breaks off into icebergs. These shelves act like corks, slowing down the glacial flow. In a stable system, the glacier advances slowly enough that snowfall replaces the ejected icebergs, and the amount of ice stays the same. For more than 7,000 years, West Antarctica's ice sheet has been relatively stable.

But that's not the case anymore. At some point in the past century, the atmosphere and the ocean changed. Ice was melting, and the glaciers were shedding ice faster than snowfall could keep up.

In 1970, the American Geographical Society published a topographical map of Antarctica. Back then, Antarctic mapping expeditions meant crawling over the surface in a glorified snowmobile, labs and seismic survey equipment in tow. Examining the map at Ohio State, Hughes noticed something about two glaciers called Pine Island and Thwaites: The cork wasn't big enough to stop them. Worse, if warm ocean water melted away the ice sheet underneath, the glaciers would drain ice even faster.

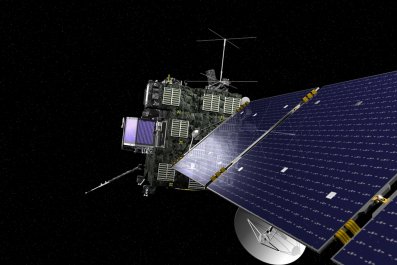

More than a decade passed with few scientific developments. But by the 1990s, the technology was getting better. Now, instead of ice tractors, teams of pilots and scientists were flying Twin Otter prop planes, heavily laden with ice-penetrating radar, magnetic sensors and GPS. The Ross Ice Shelf, south of Pine Island and Thwaites, seemed to be flowing and melting most rapidly, so that's where they started mapping. Where ice meets earth, is it slippery? Craggy? Hilly? These clues reveal whether a glacier will likely speed up or slow down. A ridge, for example, creates friction that impedes ice flow, the way rumble strips slow cars on the highway.

The Ross Ice Shelf "looked like total chaos," says Blankenship, who led many of those airborne surveys. "But if you stood back and took a long view, they were pretty much in a steady state."

The real chaos, as Hughes predicted, was happening over at Pine Island and Thwaites.

The Amundsen Sea Embayment, home of the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers, is a remote corner of West Antarctica, hundreds of miles from the nearest science station. It is prone to high winds and snowstorms that diffuse the world into a dizzying, monotone gray. Blankenship says there has never been a week in recorded history where it stayed clear.

Yet in the southern summer of 2004–2005, the Twin Otters found enough clear sky to map its subtleties. Since then, with maps in hand, scientists from around the world have returned every year and pumped out mounds of alarming research. The work has begun to coalesce, generating some of the most damning signs of climate change yet. A study published in March, for example, showed that six glaciers, including Thwaites and Pine Island, are shedding ice 77 percent faster now than they were in 1973.

Science or Politics?

Since the beginning of the 20th century, sea level has risen about 1.7 millimeters annually (less than one-tenth of an inch). The scientific consensus is that between now and 2100, it will rise somewhere between one foot and three feet. But many calculations to date have not considered West Antarctica. Now it seems more likely than not we're going to hit the high end of that estimate.

Oceanographers are still piecing together the full picture of what's causing West Antarctica to collapse, but they believe the warmer atmosphere is causing stronger winds, which in turn influence ocean currents. "Water melts ice more effectively than air," says New York University oceanographer David Holland. He has been trying to understand the strange movements of a warm ocean layer called the Circumpolar Deep Water. Typically, this water stays safely beneath Antarctica's continental shelf. But in the 1990s, scientists realized it was creeping up along seafloor troughs and eating away at the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

"These changes are related to climate warming," NASA's Rignot told reporters recently. But no carbon tax can save this ice sheet—"the collapse of this sector of West Antarctica appears to be unstoppable." To this, another climate scientist tweeted: "Scary."

Is this all alarmist rhetoric, as Hughes suggests? Or are climate change Cassandras justified in their dire language? Last year, a group of researchers asked that question. They reviewed the literature and discovered that the opposite is true. Scientists were actually more likely to cautiously scale down their predictions—including those for West Antarctica. The researchers even coined a phrase for the phenomenon: "erring on the side of least drama."

Hughes revels in being contrarian. After a born-again experience in 1966, he became deeply Catholic and has crusaded against abortion using bloody pictures of aborted fetuses. In 2001, a Catholic church banned him from the premises for displaying one of his gruesome pictures there. He has been cursed at and spit on.

A Republican voter, Hughes insists his politics has never guided his science. In the case of global warming, he says, "What I know about climate science influences my politics." That's because he believes the changes will happen so slowly, humans will have time to adjust. He says climate change urgency, typified by Al Gore, is a left-wing politicization of the science. On the other hand, he doesn't work with or actively support right-wing think tanks, like the Heritage Foundation or the Heartland Institute, that actively deny human-caused climate change, either. Hughes stays above the fray, or as he puts it, "beyond the pale."

One last irony: Now that everyone agrees Hughes was right about West Antarctica way back in the 1970s, he says he isn't so sure it's doomed. After all, he says, Churchill's "soft" Italy proved treacherous for the Allied forces. In many ways, this is a testament to Hughes's humility in the face of glaciers; he knows enough to know how much he doesn't know.

"I'm not convinced the dynamics of ice streams are known well enough to make reliable predictions that far into the future," Hughes says. "So I'm going to maintain my belief that I might've been wrong like Churchill."

SEE THE LISTS: Top 10 Green Companies in the World | Top 10 Green Companies in the U.S | Full World Rankings | Full U.S. Rankings

Our Green Rankings Section