"The clock is ticking." Over the past seven months—since she was put in charge of ridding Syria of its chemical weapons—Sigrid Kaag has uttered the phrase more times than she can count.

Kaag, 53, whose official title is special coordinator for the joint mission of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and the United Nations, previously worked for Royal Dutch Shell in the U.K. She is blond, statuesque, Dutch and speaks eight languages. She leans toward silk power suits in pastel colors and has darkly varnished nails. There is a steely edge to the woman who is disposing of Syria's chemical arsenal. Kaag wears elegant heels, but you get the sense that she prefers to be able to hit the ground running. Fast.

And she has to. According to Kaag's spokesman, Charbel Raji, a large part of the chemical weapons program in Syria has been eliminated and the deadline for completion is still the end of June. But, Raji says, "it is now evident that some activities related to the elimination of the chemical weapons will have to continue beyond the original June 30 date."

On top of performing one of the world's most delicate tasks in full public glare, Kaag is also a wife and a mother of four, ages 11 to 19. Her life moves between a hotel room in Damascus, The Hague—which headquarters the OPCW—the U.N. in New York and Nicosia, Cyprus, where the disarmament operation is based.

She is rumored to replace the former U.S. peace envoy to Syria, Lakdhar Brahimi, who U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said faced "almost impossible odds" in his attempt to halt the Syrian civil war because the international community was so "hopelessly divided." If Kaag is given the post, she would become the chief negotiator in the world's most pressing international crisis.

Kaag has plenty on her plate already. "Yes, it's a lot," she says with a smile. But there are no complaints. Kaag says when she took the chemical weapons job, she knew there was a limited time frame. She decided she could put up with the hotel rooms, planes and exhaustion because in the end there would be a massive payoff.

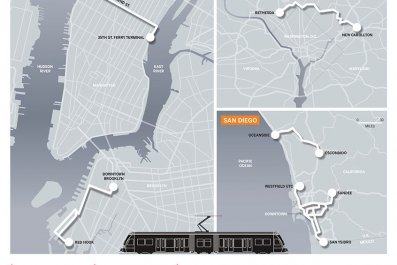

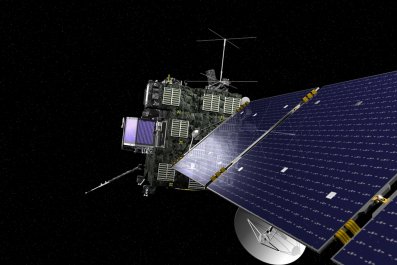

According to the OPCW, Syria's chemical-warfare program is primarily based on binary systems, which means two toxic substances have to be brought together to create a highly toxic chemical warfare agent. These less toxic agents—stored in bulk containers, not in warheads—are transported by Kaag's team to the Syrian port city of Latakia. From there, they are moved by Norwegian, Danish and British ships to the MV Cape Ray, which is anchored off Italy, where the complicated destruction process begins.

In addition to tracking the agents and making sure the chemicals are destroyed, in accordance with international law, Kaag and her team must answer many questions: Are the Syrians handing everything over? Can the weapons fall into the wrong hands en route? Is everyone working toward the same deadline with the same intentions?

Kaag says, "It's about trust and transparency." She has no choice but to trust the Syrians.

Last September, in the wake of chemical attacks in Ghouta and at the urging of the Russians, who wanted to prevent U.S. military intervention, Syrian President Bashar Assad volunteered to dispose of the country's chemical weapons. But for Syrians, the disposal does not signal the end of the war, or even a halt in the bloodshed that has already taken more than 150,000 lives. It is merely, as officials say, the "timely elimination of [the] chemical weapon program of the Syrian Arab Republic."

Kaag—a fluent Arabic speaker ("Her Arabic is perfect," says Raji. "I wish she would do more interviews in Arabic, but she likes to be precise, and there are a lot of technical terms.")—knows the region well. Among her many previous posts was one for UNICEF in Jordan as regional director for the Middle East and North Africa.

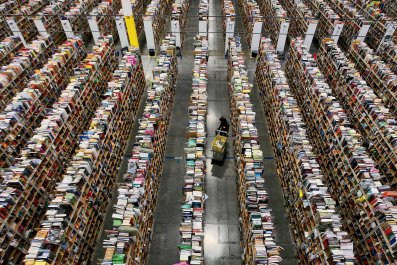

During that time, Kaag became more involved in the humanitarian sector—dealing with vaccinations, child labor and child marriage. Given her background in crisis zones, she is fully aware of the enormous human tragedy unfolding around her as she carries out her mission. And her dogged dedication to deadlines appears to be working. A little more than five weeks from the deadline, the OPCW reported the destruction of "all declared piles of stocks of isopropanol [the most dangerous of the chemicals involved] by the Syrian authorities."

"Only 100 metric tons of chemicals—or nearly 8 percent of Syria's declared stockpile—remained at a single site," Michael Luhan, the OPCW's spokesman, said on May 22. "They had been packed and remained ready for transportation."

One would be wrong to assume this brought a great sense of satisfaction for Kaag. "I don't focus on my feelings. I focus on the evidence," she says, speaking to Newsweek from a fluorescent-lit cubicle high up in the United Nations Secretariat, where she has just finished presenting an update to the Security Council.

It was early evening, and the Secretariat was eerily empty—except for Kaag's office, where she sat with two of her aides. She looked tired and had spent all day in back-to-back meetings; she would be getting up early to fly to Damascus the next day.

Her English is without accent, clipped and precise. A former colleague says Kaag is "tough"—intending it as a compliment, meaning she gets what she wants. Another says her future in the U.N. will be "stratospheric" because she is completing this mission so efficiently.

Kaag was born in The Hague in 1961, the daughter of a classical pianist, and educated in Holland and at Exeter and Oxford universities in the U.K., where she studied Arabic. "I wanted to do something different," she says.

Her attraction to the Middle East started in high school, where she came of age against the backdrop of the high drama of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. After her university studies, she worked for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs before getting a job at the U.N. After UNICEF, she worked for the United Nations Development Program, where she was the deputy to Helen Clark, the former prime minister of New Zealand. Clark, one of the few women heading a U.N. agency, is also regarded as trailblazing and energetic, outspoken and committed. In the gray-suited world of clubby U.N. bureaucrats, these women stand out.

"Look, we have 45 more days [from early May] to destroy the chemicals," Kaag says, referring to the June 30 deadline set forth by the Security Council. "My job is to get the job done."

Meeting the deadline has not been easy. Kaag first had to work to gain the trust of the Syrians "and to make them adhere to deadlines." She does not say it, but it's known they have not always been forthcoming. Equally difficult has been getting access for her team, which often has to travel on roads in the hands of radical opposition groups that are not inclined toward peace. Nor are they friendly toward U.N. workers.

On May 27, this became frighteningly apparent when two members of the OPCW fact-finding team—not part of the joint OPCW-U.N. mission, Raji points out—were attacked in the region of Hama, as they were driving to a chemical weapons location. Kaag has not commented on this incident.

Most of her current life is spent in Damascus, in her combined office-bedroom in a luxurious but rather lonely hotel in the center of the city. "I can't really go anywhere," she says, because the security is so tight. There are curfews, and she is surrounded by security details. She can't wander down to the Old City to shop or stop for a glass of tea, even if she had the time.

Kaag is not a scientist or a chemical engineer, and when she was appointed by Ban on October 16, she admitted the learning curve was steep and fast. She faced "a lot of new territory," she says. "But I have been supported."

Kaag starts the day at 6:30 a.m. in the gym, to clear her head. "Sometimes I go twice a day—it's all there is to do when I am not working," she says. She hits the phones early to speak to Europe, meets with her team, then starts a round of meetings—or wrangling—with her Syrian counterparts, drafting updates and holding town hall–style meetings with her staff.

As night falls and the calls to prayer from the muezzin echo throughout Damascus, it's still late morning in New York—and calls and requests are still pouring in.

Kaag's husband, Anis al-Qaq—a dentist—is a Palestinian. Her children—Jenna, 19, Makram, 15, Adam, 12, and Inas, 11—grew up sharing her international perspective. Two live in Jerusalem with al-Qaq, Adam is in boarding school in Geneva, and Jenna is spending a year between school and university in Holland.

"It's a different perspective," she says of balancing motherhood with work, but she adds she is lucky because "my husband, at the moment, is doing all the organizing. He's doing all the driving back and forth."

But there are obvious frustrations, which Kaag ticks off. "Things you cannot control," she says, speaking before the attack on the OPCW fact-finding team took place. "The security conditions—we don't have military, so we have to be reliant on the good will of many channels." By this she means the Syrian government, which is not always transparent.

"I remind all of my colleagues of what has happened to the people of Syria," she says. "All I can hope is that the little we can do can enable.… " And she trailed off. "A lot has been accomplished, a lot of boxes have been ticked," she says. "But there's a last push to get the matériel out."

Is she happy about that? She looks solemn. "We can never be happy knowing people are dying," she says. "I feel no joy. I feel only relief knowing that we are, in some way, helping."