Pastor Bob Fu knows about life on the run. Back in 1996, when he and his wife lived in Beijing, they spent two months behind bars because of their work in the underground Protestant "house church" movement.

Friends warned they'd be jailed again soon. The couple hid out in the countryside, then escaped to the then-British colony of Hong Kong via Bangkok. Friends—and strangers—pulled strings so Fu's wife could give birth in a local hospital and the couple could gain asylum in the West. When they finally boarded a flight for America in June 1997, "we knew what it meant to be rescued," recalls Fu, now based in Midland, Texas. "What it meant to feel desperate."

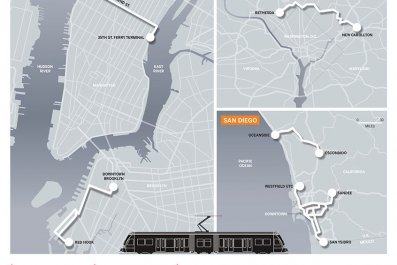

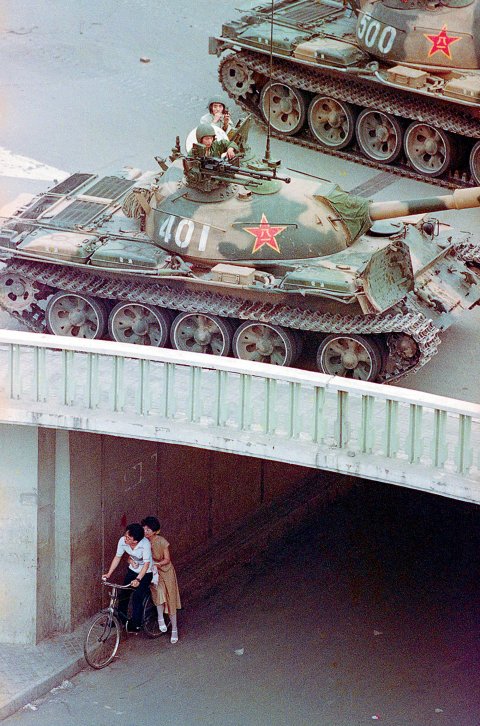

Inspired by that experience, Fu now runs a nonprofit called ChinaAid. It works with thousands of volunteers in China to help victims of injustice. When blind dissident Chen Guangcheng escaped from house arrest and sought urgent refuge in the American Embassy in Beijing, Fu furiously worked his contacts in Washington, D.C., and the media to help Chen obtain a student visa for the U.S. And in "extraordinary" cases, says Fu, ChinaAid launches rescue missions to help persecuted Chinese escape through its own underground railroad, extractions whose methods have been informed by those who have come before—and which started in the wake of the June 4, 1989, massacre at Tiananmen Square. They are the progeny of "Operation Yellowbird."

It was only last year—nearly 18 years after their escape—that Fu and his wife learned they had received crucial support in Hong Kong from a top man in the now legendary organization that called itself Yellowbird: an underground network of sympathizers shocked into action after Tiananmen Square.

Yellowbird used whatever tools it could muster to spirit dissidents out of the country. Gangsters lent smuggling boats. Cantopop stars donated concert proceeds. Hong Kong police handled disguises. An academic study by Shiu-Hing Lo said the CIA provided scrambler phones, night-vision gunsights and more.

By 1997, Yellowbird had helped rescue up to 500 Chinese activists, including 15 of the 21 Tiananmen protest leaders on Beijing's "most wanted" list. "Though I never wanted to leave China, Yellowbird was very important," recalls New Jersey-based exile Wang Juntao, whom Beijing called a "black hand," or mastermind, behind the 1989 protests. "Without Hong Kong people's support, without global attention, without an escape plan, China's democracy movement would have suffered much, much greater losses."

Twenty-five years after the Tiananmen bloodletting, Yellowbird's legacy is a bright ray of light in China's still bleak political landscape. When I first reported on Yellowbird in 1996 for Newsweek, organizers warned that many details had to remain secret to safeguard ongoing missions. ("Nobody told me at the time that I owed thanks to something called Yellowbird," says Fu.) Now increasing numbers of organizers are going public with extraordinary tales of escapes from China that seem to have sprung from the pages of spy novels.

But the tales of Yellowbird's derring-do are not just a matter of history. The organization worked for years after 1989, and its most potent legacy extends very much to the present day. At minimum, it inspired successor networks—like Fu's—that operate safe havens and orchestrate safe exits for a variety of Chinese activists on the run.

The pressures that make people take flight keep mounting. Communist officials plan to demolish or forcibly remove crosses from 64 Protestant churches in Zhejiang province, says Fu. In May, Beijing kicked off an "ultra-tough" anti-terrorist campaign to suppress violence in largely Muslim Xinjiang province, wracked by the bloodiest attacks in years. Recently, 55 suspects were sentenced in a sports stadium packed with 7,000 spectators, a chilling scene evoking the excesses of Chairman Mao.

Tiananmen Anniversary Clampdown

The events of June 4, 1989, united an odd-bedfellows alliance of human rights activists and church workers, foreign diplomats and members of Hong Kong's notorious underworld gangs, the triads. "That everyone, even the Mafia, helped Yellowbird shows just how unpopular, how morally off, the crackdown was," says Bao Pu, a Hong Kong publisher. (His father, Bao Tong, then a senior party Chinese Communist Party cadre sympathetic to the 1989 protesters, was the first person arrested in the crackdown.) "No matter what you do for a living, nearly everyone knows between right and wrong."

But not quite everyone. To prepare for the 25th anniversary of Beijing's day of carnage, authorities tried harder than ever to suppress all public mention of June 4, a trauma that gripped the nation, nearly split the ruling Communist Party, and killed more than 1,000 protesters. Today, officialdom deems Tiananmen Square such a sensitive venue that in May a young factory worker visiting Beijing who posed in the square for a selfie—and flashed a "V" for victory sign with his fingers—was detained.

The Tiananmen anniversary triggers a security clampdown every year, usually beginning in mid-April. But this year, the campaign kicked off especially early. AIDS activist Hu Jia was placed under house arrest in February. Bao Tong, the former senior policy adviser and now a political prisoner who remains under a form of "soft" house arrest in Beijing, was told back in January not to talk to the media about June 4. Police have nabbed activists and scholars, an independent journalist and a Japanese paper's Chinese news assistant, an artist and a prominent lawyer, gay rights advocates and even Buddhists while they were meditating. "Stability maintenance" is the government's Orwellian catchphrase of the day.

The "Mantis Stalks the Cicada"

Many former protest leaders who mourned fallen comrades on June 4 may well owe their lives to Yellowbird. The network derives its name from an old Chinese proverb: "The mantis stalks the cicada, unaware of the yellow bird behind." Its first rescue was a group of three students, including Li Lu, who later went to Columbia University and became a fund manager advising on China investments for Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway company.

A Yellowbird organizer told me in 1996, "I sent people to meet Li Lu, and he got into a car beside a uniformed policeman. He thought he was being arrested! I felt that was the safest way to transport him. If stopped [by the authorities], the cop would say Li was in his custody. Actually, he really was a genuine cop.''

Of all the great escapes, few match that of former student leader Wuer Kaixi. After June 4, seven friends smuggled him out of Beijing to the southern coast of Guangdong province. At one point, he was shut inside the stifling trunk of a car.

In May 1989, during an unusual televised meeting between student representatives and hardline Premier Li Peng, Wuer, who was on a hunger strike, appeared wearing a hospital gown and clutching an oxygen bag. He chided the premier for being late. Unsurprisingly, the talks fizzled. Li ended the dialogue with a brusque "goodbye."

Wuer's insouciance in the Great Hall of the People and his impassioned speeches in the square were memorable. But they ended up making him No. 2 on Beijing's "most wanted" list after the army opened fire in Tiananmen on June 4.

Because many Guangdong residents regularly watched Hong Kong television, they easily recognized Wuer, so he couldn't move safely in public. A sympathizer rushed to Hong Kong with a Polaroid of him clutching the same day's newspaper with a handwritten plea: PLEASE SEND HELP. Hong Kong politician Szeto Wah, by then deeply involved in organizing a lifeline for Tiananmen fugitives, saw the photo. Yellowbird flew into action.

One mob boss bankrolled the mission. The first two rescue attempts were aborted. A third got under way when Wuer glimpsed infrared lights flashing in the darkness off a deserted beach. He and his then-girlfriend scrambled over sharp oyster beds to reach a sleek powerboat that zoomed the exhausted, bloodied fugitives to Hong Kong. French diplomat Jean-Pierre Montagne awaited their arrival, ready to whisk them to Paris with passports, tickets and visas.

Recently, Wuer—more mature now, with a son nearly 21, the same age he was a quarter-century ago—told me his escape had cost nearly $100,000 "just for the speedboat ride alone. An underworld guy called Brother Six paid for it, I was told. So when I went to Hong Kong in 2004, I thanked him for saving my life."

Brother Six is another larger-than-life Hong Kong character: underworld figure, speedboat king, car smuggler extraordinaire. He nearly fainted when he saw images of the June 4 carnage on TV. Soon afterward, he met two wealthy Hong Kong executives in a Kowloon hotel to come up with a plan.

Brother Six and his team specialized in the transport and logistics for the rescues; they helped more than 100 protest-movement figures escape. The more famous those figures were, the more easily and quickly they were granted asylum—but the more it cost to get them out. "Everything in Hong Kong," says one insider with a smile, "is supply and demand."

Authorities began to suspect that Yellowbird was helping dissidents and organized sting operations to seize some of its members. When a friend told scholar and activist Wang Juntao that Yellowbird would help him escape, Wang said he didn't want to leave China. "But my friend said, 'A meeting's been set up in Changsha. You should go and then decide to flee or not to flee,'" Wang recalls. "But when I arrived at the Changsha train station on November 20, I was immediately arrested."

It had been a Chinese police sting from the start. Wang and his colleague Chen Ziming were detained, and each was sentenced to 13 years. Two of Brother Six's men were also jailed. (Brother Six later negotiated with mainland authorities for the release of his men; in return, he agreed to stop smuggling out dissidents. Both Wang and Chen were released on parole in 1994.)

Mystery still cloaks just how deeply Yellowbird reached inside the mainland bureaucracy. Stories are now emerging about relatives of high-ranking cadres (who must remain anonymous for now) helping activists escape. "People inside the system, senior party officials or their family members, helped smuggle people out. I know that about a dozen were imprisoned, some for more than a decade," says Bao Pu, the Hong Kong publisher. "Recently, I met the wealthy son of a general, from the so-called red second generation [the sons of Red Army members who fought alongside Mao during the revolution], who spent three years behind bars. Nobody knows how much people like these suffered."

Publicly, the regime hasn't wavered from its hard line regarding Tiananmen, deeming it a "counter-revolutionary rebellion." And as the years have passed, Yellowbird's room to maneuver became increasingly cramped. Fugitives from June 4 kept trickling into Hong Kong into the '90s. But a problem loomed. The British-administered enclave was due to revert to Chinese control on July 1, 1997. That meant escapees would have a hard time obtaining asylum (or even landing in Hong Kong) after the handover. (France had been especially welcoming; its consulate issued papers to activists without waiting for approval from Paris.)

Meanwhile, by 1996 the most high-profile heroes of Tiananmen Square either had been jailed or had escaped. That left about 80 escapees who were less famous, less sophisticated and less articulate when they tried to persuade foreign governments they were fleeing repression.

Bob Fu, who had landed in Hong Kong in the autumn of 1996 with his pregnant wife, was among them. He was not famous—"a small potato," in his words. The couple faced an uphill asylum battle. In 1989, he had led students from his university in Shandong, a coastal province south of Beijing, to join the protests in Tiananmen. Afterward, he had to write confessions but avoided jail time.

After converting to Christianity, he and his wife opened an independent Bible study class in Beijing and became active in a so-called house church congregation. (In these communities, Chinese Christians hold underground services in private homes to escape the control of state-sanctioned church authorities.) After the couple were briefly detained in 1996, Fu's wife became pregnant in violation of Beijing's strict one-child-only family planning regulations.

Fearing another detention, they ran and hid. "Then," Fu recalls, "a sort of miracle happened." An Australian missionary friend put them in touch with a Beijing travel agency. They said they wanted to join a Southeast Asian tour. An agent got them passports based on fake employment letters from a big tech company. Inserted into a 20-person Chinese tour group headed for Bangkok and Hong Kong, the couple ditched the others after arriving in the British colony.

In Hong Kong they encountered a mountain of red tape—and a climate that had already begun to change as the historic handover from Britain to China approached. "Week after week, we phoned one consulate after another in Hong Kong asking for help," Fu recalled. "'No, no, no' came the answer. Few foreign diplomats even knew what a house church was, so we had to explain everything from the beginning. It was tense."

If the green light didn't come before the handover, Fu would be trapped, a man without a country. But behind the scenes—and in Washington, D.C.—friends pulled strings furiously. At the last minute, the couple was granted asylum in the U.S. and caught a flight for America on June 27, the last working day of the British colonial administration.

Before the deadline, Yellowbird organizers had scrambled to help clear the backlog of dissidents in Hong Kong still searching for safe havens. And they succeeded. Today, at least on the record, they claim the great escapes are no more.

"Yellowbird is an illustration of Hong Kong's unique role, dating back to the Qing Dynasty [the last imperial dynasty, which ended in 1911]. Back then, people also came here to escape persecution," says Lee Cheuk-yan, head of the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, which lent backing and funds to the protest movement. "It is a lighthouse for people in China, a safe exit, a place where the struggle for democracy can take root. But after 1997, the possibility of asylum closed down."

Yellowbird 2.0

Though few wind up in Hong Kong now, victims of injustice continue to flee China. The more recent rescue missions are lower-key compared with the headline-grabbing Yellowbird triumphs of old. The people-smuggling routes, the methods and even the profiles of escapees have changed with the times.

Today they are less likely to declare they're risking all for democracy and more likely to rail against religious persecution and ethnic discrimination or express localized grievances. And as technology has improved—everyone now has a smartphone—so too have the logistics of escape. Today, some fugitives just walk across China's porous southwestern border into Indochina or board planes using passports obtained under false pretenses.

But the knowledge—the ability to run an escape undetected—has been passed down over the years since 1989. In 2009, Geng He, the wife of human rights lawyer and political prisoner Gao Zhisheng, was under relentless, in-your-face surveillance at home. (Gao often represented victims of repression, including practitioners of the banned quasi-Buddhist sect Falun Gong. He himself had been in and out of detention several times.) Geng told a kind roadside vendor near her home about her family's travails. The next day, as she was buying fruit, he wordlessly passed her some change, and a scrap of paper.

On it were instructions that launched Geng and her two children on a two-week-long pilgrimage to freedom. They used train tickets, fake IDs, a cellphone and several SIM cards provided by an anonymous man. After they arrived in southwest China, Gao's two preteens crossed into a neighboring country disguised as ethnic-minority children from a local hill tribe. When all three of Gao's family members reached Bangkok, Fu phoned him with the news. "He was very relieved," Fu says.

Soon afterward, Gao disappeared again. He is now reportedly serving a three-year prison term in distant Xinjiang.

As Fu learned, kids are tricky passengers on the underground railroad. Five years ago, his nonprofit ChinaAid mobilized a rescue of the family of Guo Feixiong, another legal activist and a colleague of Gao's. When Fu couldn't obtain travel documents for two of Guo's children to leave China, the persistent pastor gave them his own kids' passports. The trio hopped a plane for Dallas, with Guo's children posing as Fu's. (Potential people-smuggling charges against Fu were dropped after an investigation.)

Fu's network is relatively modest in scale. It has helped spirit about a dozen Chinese out of the country since 2002. They're a diverse crew: Protestant house church leaders and Falun Gong followers fleeing religious persecution, an activist judge, families of political prisoners, a woman who defied family-planning rules and was forced to have a risky late-term abortion. Some cases cannot be publicized yet, to protect escapees still waiting for safe harbor. One case involves relatives of a wealthy Chinese man who'd been persecuted by ex-Politburo politician Bo Xilai, who in 2012 was purged, tried and sentenced to life for corruption and abuse of power.

Fu says he's moved to help dissidents' families when the father or husband is detained. "It broke my heart to read reports of security people hanging out in the living rooms of political prisoners' families, playing poker 24 hours a day," he says. "The underground railroad gives encouragement to people such as Gao and Guo. It lets them know their families are OK."

Since 1997, much of the overland smuggling action has shifted to the rugged hills and rivers of southwestern China. For years, North Korean escapees have crossed China on their way to other countries. And most recently, the surge of unrest and violence in Xinjiang, in China's far Northwest, has sent many Muslim Uighurs fleeing an ever more intense government crackdown. Cambodian and Laotian authorities have caught groups of Uighur border-crossers and sent them back to China. Last October, up to 100 Uighurs were arrested on the Chinese side of the frontier with Laos, where they were hoping to flee after intense police activity in Xinjiang, Radio Free Asia reported.

Beijing's continuing crackdown may portend yet more traffic along the nation's myriad escape routes, as the regime struggles to contain the escalating violence, which it has blamed on Uighur separatists. Last October, three Uighurs rammed their vehicle into crowds in Tiananmen Square, killing themselves as well as two others. And 29 people were slashed to death in a Yunnan province train station, an attack also blamed on Uighur jihadists.

Then, just last month, several massive bomb blasts at a market in Xinjiang's capital of Urumqi left 43 dead and 94 wounded. "It's all part of the same story, the story of living under authoritarian rule," says Bao Pu, the Hong Kong publisher. "Unfortunately, it sometimes manifests itself as a racial or religious issue. But the root cause is the system itself. People feel hopeless."

The Comeback Kid

Chinese attitudes toward exile have evolved as well since the heyday of Yellowbird. Today's Chinese dissidents have a less idealistic view about life in the West and are more aware that exile can be "a long, painful, lonely journey," says Hou Xiaotian, who was jailed four times after 1989 because of her campaigning to free political prisoners. They included her then-husband Wang Juntao, at the time serving a 13-year sentence.

She left China legally in 1993, worked on Wall Street for a decade and negotiated with officials to permit her to return home if she focused on her business. She agreed. "For five years, I was in politics as an activist. For 10 years, I was on Wall Street. Now it's time to turn a new page."

As paradoxical as it may sound, former student leader Wuer Kaixi has been trying his best to come back to China, too—and to be arrested. Last November he made his fourth unsuccessful attempt to return to China by boarding a flight to Hong Kong, the city that once showered him with a hero's welcome. Hong Kong authorities trundled him straight onto a Taiwan-bound plane.

"I want to go straight to jail in China," he declares with an impish grin. "[I want] to put the Chinese government in the difficult position of holding an open trial—my trial—on the whole topic of Tiananmen, to have them officially charge me for something I did back then."

For a moment, Wuer reveals a flash of youthful bravado, a hint of the idealistic 21-year-old I first met during the chaos of Tiananmen. What if things go sour? I ask him. Does Yellowbird still exist as an option?

He measures his words carefully. "Yellowbird is still happening," he says. "Not as much as before, of course. Only when needed. As for exile, actually, I lost my freedom when I went into exile.''

Brave words. Just like 25 years ago. Perhaps rendered a bit braver with the knowledge that, with luck and the right friends, you can run and you can hide.