Consider the coyote.

Not the wolf-like creature (canus latrans) that has roamed the wilds of North America for millions of years and is now sometimes spotted in urban environments as diverse as Chicago and San Francisco, but the coyote-as-symbol that Chuck Jones crashed into as a child. "I first became interested in the coyote while devouring Mark Twain's Roughing It at the age of 7," the animator recalled in his autobiography, Chuck Amuck. "The coyote is a living, breathing allegory of Want," wrote Twain. "He is always hungry. He is always poor, out of luck and friendless.…"

It was that irrational, almost mythical beast that inspired Jones's signature character, Wile E. Coyote, who wants beyond all reason to consume the Road Runner and attempted to do so in a series of Warner Bros. cartoons that began in 1948 and petered out in the 1960s, after Jones had stopped directing them. The look of the cartoons is timeless, and so, it seems, is their appeal.

"Chuck found a Santayana quote you may have seen: 'A fanatic is one who redoubles his effort when he's forgotten his aim,'" says Jones's daughter, Linda Jones Clough. "That's the Coyote to a T; he is an obsessive-compulsive. Obviously there are many other things that he could eat, and yet he cannot give up the idea of this one thing. It seems to me that the reason the cartoon's so enduring and strikes so many people: that feeling of 'I've got to have this thing! And I really can't justify why I need this so much, but I do.'"

We are talking about Clough's father as a major retrospective of his work, What's Up, Doc? The Animation of Chuck Jones, opens at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York before moving on to multiple cities in the U.S. I had just come back from a Wearable Technologies Conference where I met a guy hawking RocketSkates—just the kind of thing the Coyote employed when trying to catch the Road Runner in the painted desert. (Actually, they're battery-powered, but "RocketSkates" sounds better.) Their creator, Peter Treadway of ACTON, Inc., told me had originally wanted to name his company Acme, in homage to the company in the cartoons.

"I don't know who would stop him," says Clough. "The word Acme has been used a million times, and it can't be copyrighted. Warner Bros is stomping up and down and having smoke come out of their ears because they can't control it."

Her father, with whom she worked as a producer of animated shorts in the 1990s, became enamored of the brand as a child. "My sister Dorothy fell in love with the title Acme, finding that it was adopted by many struggling and embryonic companies because it put them close to the top of their chosen services in the Yellow Pages," he wrote. The name took on a greater significance in the cartoons, as one of The Rules of Coyote vs. Road Runner (as outlined inChuck Amuck) stated, "No outside force can harm the coyote—only his own ineptitude or the failure of Acme products." (This is followed by Rule 7: "All materials, tools, weapons or mechanical conveniences must be obtained from the Acme corporation.")

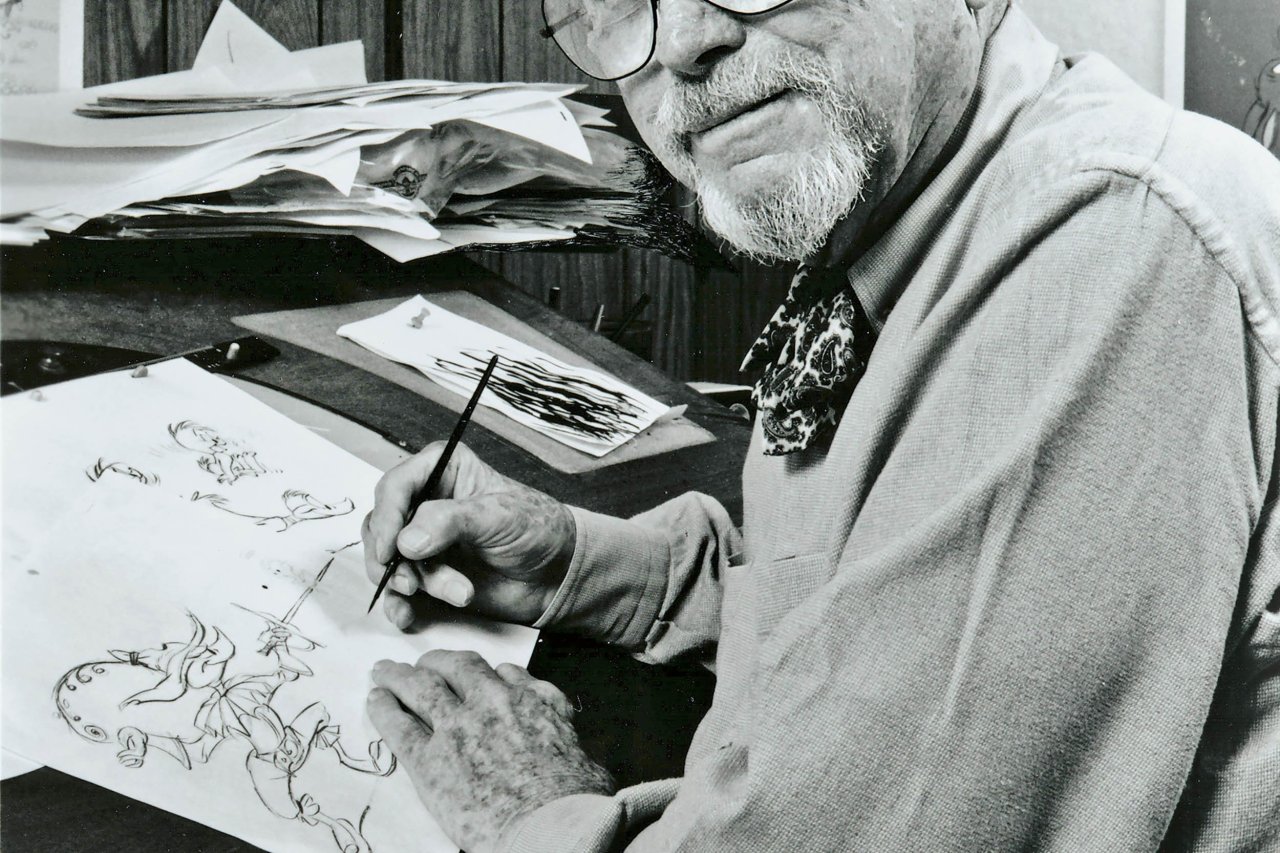

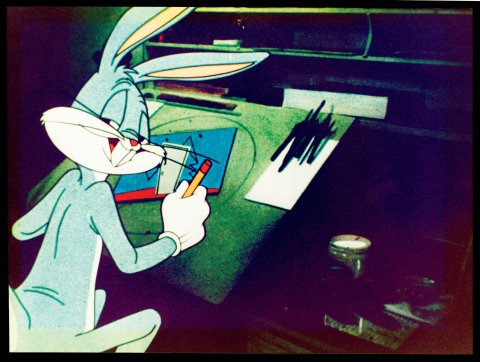

Chuck Jones trained as a fine artist at what is now the California Institute of the Arts and began working as an animator at Warner in the 1930s under the legendary director Tex Avery. There, working beside animators and writers such as Friz Freleng and Mike Maltese, the young Jones learned a respect for the logic of a story and the importance of timing as they honed the Warner Bros. characters they created and developed: Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Elmer Fudd.…

"Most of our characters are not noted for triumph," he wrote. They were, rather, "inept contenders with the problem of life."

It was Bugs Bunny who changed the most under Jones and company. "In the early pictures he was a very different character," recalls Clough, "more like Woody Woodpecker. He was always ready to run, crouched down and scared. Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones had a lot to do with standing him upright—as Chuck used to say, 'He stands on his back legs 'cause he's not afraid anymore.'"

Jones, who died in 2002 at the age of 89, said he had to make the rabbit his own. "I could not animate a character I could laugh at but could not understand," he wrote. "A wild wild hare was not for me; what I needed was a character with the spicy, somewhat erudite introspection of Professor Higgins, who when nettled or threatened, would respond with the swagger of D'Artagnan as played by Errol Flynn, with the articulate quick-wittedness of Dorothy Parker—in other words, the Rabbit of My Dreams."

Today Clough is a director of the Chuck Jones Center for Creativity in Costa Mesa, California. (It was the center, in conjunction with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that curated the original show, before collaborating with the Smithsonian and the Museum of the Moving Image.) She bemoans the fact that her father's cartoons cannot be seen on television today (they were a staple of Saturday morning programming for decades) and that the powers that be don't see their adult appeal.

"They weren't made for children," she says. "They went out with gentle little pictures like I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang.… The reason they weren't scatological or had a lot of adult humor was because of censorship. [The writers] were constrained to find humor in things that weren't bodily or sexually referenced."

Unlike many kids' cartoons today. To say it was a simpler time misses the point: The great Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons of Hollywood's golden age were too hip for some producers at the time. "Just what the hell does all this laughter have to do with making cartoons?" a particularly dim-witted overseer once asked the cartoon staff at Warner.

But they had the last laugh, as the likes of Bugs and Daffy and Jones's other great "scentimental" creation, Pepe LePew endure far beyond the frame. Mickey Mouse may be more universally recognized than Bugs Bunny—but quick, what is Mickey's signature line?

"FromHair-Raising Hare (May 1946) on, I did not have to ask for whom the rabbit toiled; he toiled for me," Jones wrote. "I no longer drew pictures of Bugs; I drew Bugs, I timed Bugs, I knew Bugs because what Bugs aspired to, I too aspired to."

The kid's still got a lot of bounce.