The story of my mother's family is built on dark secrets and tragic losses—suicide, sudden death and fatherless children—yet there was always a treasured relic that transcended the pain: the many love letters my grandfather wrote to my grandmother when he was fighting in World War II, the letters that won her heart and her hand. Sally Anne Rudolph and First Lieutenant Charles Brand—Charlie, she always called him—had gone on only two dates when he was shipped off to Europe, and Sally didn't see him for two and a half years. But while Charlie was away, he wrote her almost every day.

Two dates. Gone for more than two years. Hundreds of letters.

It is a stirring, romantic and optimistic story, but it too is tinged with tragedy. My grandmother, in a desperate attempt to slough off yet one more loss in her life, confessed to us she had destroyed Charlie's letters. This was a particularly cruel twist because my family lives in the past, by predilection and profession. My parents are both historians; I am a writer. None of us had ever read these letters, but we are all captivated by their mystique. We had so many unanswerable questions: How many were there? What did they look like? What did Charlie write about? My grandmother rarely gave us details, only tantalizing glimpses of an epistolary love affair that brought her—and her offspring, vicariously—so much joy.

'Poof, He Was Gone'

Tragedy came early for my grandmother.

Sally Rudolph grew up on Manhattan's Upper West Side, in a family of widows, divorcées and perpetual bachelors. In 1926, when she was 5 years old, her father, Solomon Rudolph, leapt from a hotel window during a family vacation. Mourning was a quieter, more private monster back then; suicide almost unspeakable. Sally and her older brother, Alan, knew their father was dead, but their mother never told them how or why. Nor did she remarry; instead, she spent the rest of her life wearing the colors of mourning: black, gray and lavender. Over time, Solomon faded from family conversations and photo albums, a man so invisible that I hardly know more about him than what I've written here.

In the aftermath of Solomon's death, Helen, my great-grandmother, took an ocean liner to Europe, traveling for three months while her children stayed behind. This was possible because she was a widow with money. Her brothers, Reuben, Isaac and Benjamin, were the founders of Goldsmith Brothers Stationers, one of the largest stationery stores in the country. The family was comfortable, and that afforded luxuries like trips to Europe—and the large apartment Helen, Sally and Alan later moved into with Helen's troupe of quirky siblings.

They lived in a penthouse apartment in the Parc Vendome, a landmark building just south of Central Park. There was Helen's sister, Blanche, a divorcée at a time when most women chose to—or had to—stay with drunken, abusive husbands. Reuben walked around the apartment in his underwear and hung his laundry to dry on the terrace. Ike had a steamer trunk he kept packed so that he was ready to take the next pretty girl he met to Cuba. (Benny, the youngest, was the only brother who married; he and his wife lived nearby.) Helen presided over them all—a fashionable, well-coiffed brunette who chain-smoked Chesterfields and played cards with the men.

In a household of battered hearts and unmarried men, Sally grew up to be a hopelessly hopeful romantic. "There was always someone I was dying to have notice me," she said in 2005, during one of many extended conversations we had about her life. "But I was insecure. I had no real male-female relationships in my family, so anything that looked like romance was.…" She finished the sentence by closing her eyes and letting out a long, relaxed sigh.

In the fall of 1938, Sally arrived at Cornell University bearing her acceptance to the School of Architecture, half a dozen ball gowns and a yearning to meet her future husband. She did not consider herself beautiful, but she was: alabaster skin, strong eyebrows, big caramel-colored eyes and long brown hair that held its curl. She joined one of Cornell's few Jewish sororities, made the kind of girlfriends that last a lifetime and was voted best Jewish legs in the school.

Sally spent most of her Cornell years with a crush on a young man named Danny, who wore a homburg, carried a small dog around campus and had no intention of marrying her. "My girlfriends married guys they were going with, because the war came. So I graduated without my special boyfriend," she told me. "I guess my mother just prayed."

After graduating, she returned to Manhattan and started working in art galleries and designing the windows at prominent department stores. They were good jobs, but she had never wanted to be a career woman. Anytime a young man came over to pick her up for a date, he had to contend with Uncle Ike, who would say, "Never get married. Be like me!" There was a guy in her building, kind and smart, but he hadn't been to college (deal-breaker). Another man was charming, handsome and educated, but he lied about not having another girlfriend. And then she met Charlie Brand.

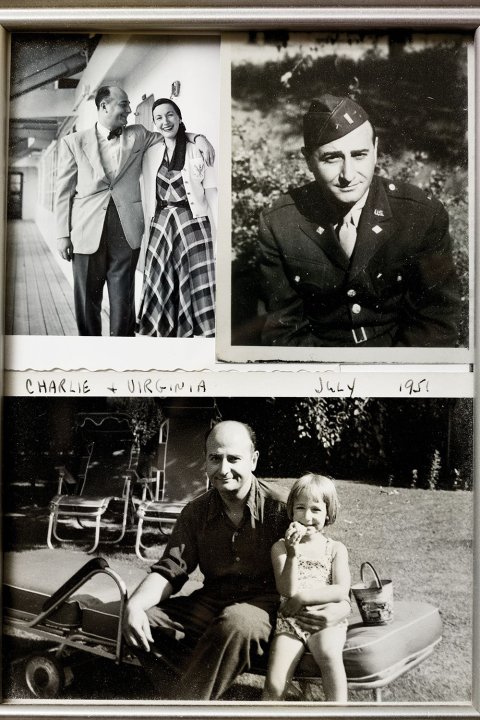

It was at a wedding in 1943—she was a friend of the bride; he was a friend of the groom. Charlie had grown up in Manhattan and attended Columbia University and then Columbia Business School, where he became a CPA. When Sally met Charlie, he was a lieutenant in the U.S. Army's finance corps, which ran the Army's business affairs. On their first date, he took her to the Waldorf Astoria Hotel for dinner and dancing. It was an enjoyable evening, she said, but she didn't see him again until months later, when he showed up at a cocktail party she was hosting with her brother.

As the party was winding down, so the story goes, Charlie invited her to dinner at his parents' house that night. Her brother joined them with his date, and the next evening, Charlie arrived at Sally's door wearing his uniform; he took her dancing and then walked her home, kissing her all the way down 57th Street.

"I got home and my mother was waiting up for me," my grandmother told me. "She always did. I said, 'I think I've met the man, Mom.'"

But before Sally and Charlie could even go out on another date, the Army deployed him to Pittsburgh. He invited her to visit. "I am going to visit Charlie, and I am going to lose my virginity," she told her mother, who replied, "Have a good time, dear."

Sally packed her bags, but the day before she planned to get on the train to Pittsburgh, she missed a phone call from Charlie: He was shipping out early and would not be able to call again.

"[Charlie leaving] was like the rest of my life," Sally said, referring to her father's suicide. "Poof, he was gone."

The Life They'd Dreamt Of

In 1944, Charlie Brand landed on the beach at Normandy after the main assault troops stormed the French coastline, and for nearly two years, he marched across Europe as part of the Allied invasion, always about 10 miles behind the front line. He arranged supplies for the troops, paid soldiers' wages, oversaw German prisoners of war, managed civil affairs for the Army in occupied Germany and drove pilots who had been shot down from the battlefield back to safety. And he wrote letters to Sally.

They had started corresponding casually during the summer of 1943, when Charlie was stationed in Gainesville, Fla., and later in Pittsburgh. By the time he arrived in England, he wrote almost every day, describing his wartime buddies and his impatience with the military hierarchy; the excruciatingly slow mail in the Army and his hatred of the Nazis. He detailed the Allied army's rush through Normandy, the final assault on Berlin. He wrote about the atom bombs dropped on Japan. He described books and magazines he had read, sent her poems and quoted philosophers. He even wrote one letter in French. Regardless of the subject at hand, he would always find a new way to say "I love you" to "my gal Sal."

Across the Atlantic, in her cozy bedroom at the Parc Vendome, Sally read and reread Charlie's letters. She told us she would often sit on her bed or in her grandmother's rocking chair, sketching out what to write in her own letters on the backs of the envelopes from him.

On May 9, 1945, the Germans surrendered, and Charlie immediately began calculating how soon he would be discharged so he could return to his Sally. He ended up having to wait nearly six months. It wasn't until October 8, 1945, that she received a Western Union cablegram:

"LEAVING 10TH ARRIVING END OCTOBER OR EARLY NOVEMBER LOVE=CHARLES BRAND."

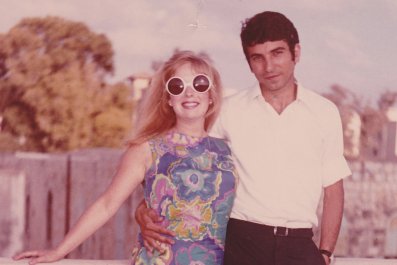

Finally, in early November, Sally stood beneath the four-sided clock atop the information booth in Grand Central Station, wearing a chic suit and waiting to see Charlie for the first time in two and a half years. He had proposed in a letter, and plans were under way for them to marry that next week, but she had decided they would wait. "I wanted to see if I was still attracted to him," she said. Sally had spent the last few days throwing up, and now, waiting to see her fiancé, she was trying hard not to be sick again.

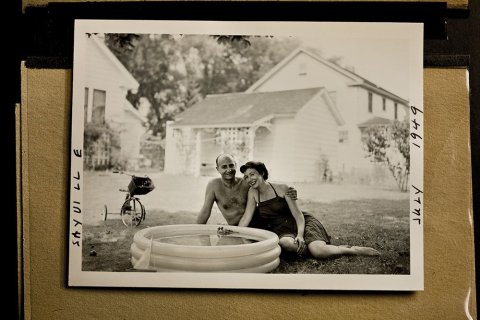

My grandmother was always maddeningly vague about what happened at this meeting, but it must have gone well because, two weeks later, she and Charlie were married in a small ceremony, then spent the next three days at the Plaza Hotel, at the foot of Central Park. "All my inhibitions were taken care of," she told me. "I remember being in the bathroom, and he was waiting outside. I said, 'Why are you there?' He said, 'I just want to be.' We didn't leave our room very much." A week later, they honeymooned in Miami Beach.

When Sally and Charlie returned to New York, they cheerily rushed headlong into married life. They had two daughters, Virginia (my mother) and Susan, and in 1952, they moved from Manhattan to the leafy suburb of Scarsdale, New York. Their house was a traditional colonial with a large front lawn, a stone path leading up to the front door. Ginny and Susie played hopscotch out front and had a swing set in back. Each morning, Charlie took the train into the city, where he worked as a vice president at Goldsmith Brothers. At night, Ginny and Susie snuggled into the couch in the den to watch Howdy Doody.

The life Sally and Charlie had dreamt of, written about and waited so long for—the one born with kisses under the street lamps of 57th Street and then nurtured through all those letters—was finally theirs. Sally had two healthy and happy children. She had her beautiful home. She had her Charlie.

On a hot July day in 1954, when Ginny was 6 and Susie was 4, Charlie suffered a heart attack on the tennis courts at Beach Point Club in Mamaroneck. Sally and the girls were down by the beach, swimming and watching the sailboats lazily pass by; they had no idea he had hobbled over to a tree and collapsed. A doctor playing on a neighboring court ran to get his medical bag as Charlie lay on the manicured lawn, dying. He was 37 years old.

Poof, he was gone.

'I Burned Them'

Sally was suddenly a 33-year-old widow with two young daughters. She was stricken with grief, but she did not want to be alone for the rest of her life, as her mother had been. She eventually started dating, but no one seemed right—until she met Stanley Drachman, a handsome bachelor who practiced medicine in nearby White Plains and loved opera. They announced their engagement at a party at Sally's home. "Someone came upstairs and said, 'You're going to have a new daddy! Go downstairs!'" my mother recalls. "I didn't want to. I wasn't sure I was ready for this."

When Sally married Stanley, she took his last name, and Stanley adopted the girls. So they, too, became Drachmans. ("We had new birth certificates," Ginny recalled. "It was as though the name 'Brand' was erased from my life, as if I was born Virginia Drachman and Charlie hadn't even existed.") Sally and Stanley bought a new house on the other side of Scarsdale. But that wasn't all Sally gave up; when she moved, she left all of Charlie behind. She distanced herself from his family. Ginny and Susie no longer visited their cousins. Sally stopped talking about Charlie. Sally told us that, before she and Stanley moved into their new house, she burned all of Charlie's letters.

Sally died in 2012, at the age of 91. In the final years of her life, especially after Stanley died and she moved to Boston to be closer to my parents, she started talking about Charlie again. I think she finally felt free to let herself remember, and to love him again. Part of this shift was a result of her growing older and looking back, and part of it was watching her grandchildren navigate dating in the 1990s and 2000s. "It was so different in my time," she often said. "You don't even know what social dancing is. Your generation is missing something." First she started talking about what it was like to meet young men in her day, and that led to Charlie, and that invariably led to his letters. My mother remembers the last time Sally mentioned them to her.

"I really should have left them to you," Sally said, regretfully. "You are the historian in the family."

"I know, Mommy. Why didn't you?"

"I just had to move on."

"What happened to Charlie's letters?"

"I burned them."

"But why? How?"

"I don't know. I just didn't want to have the letters anymore. I just wanted to move forward."

'The Most Unbelievable Thing…'

In May 2012, four months after my grandmother died and one month before my sister's wedding (the first for Sally's grandchildren), my phone rang. I remember exactly where I was standing: in the cafeteria at my office, a space lit by a wall of windows and tiny white lights suspended from the ceiling. It was midafternoon, and since I was running late, I also remember exactly how I felt when I heard my phone ring: rushed. But it was my mom calling, so I picked up.

"The most unbelievable thing happened," she said.

"Are you OK?" I asked, making a mental list of all the things that might have gone wrong.

"You know Charlie's letters?" she said. My whole life, she referred to her father as "Charlie," not "Dad" or "Daddy."

I knew all about them—or, as much as I'd gleaned from my grandmother before she died, and by peppering my mom with questions for as long as I can remember. "Yes," I replied. "The ones Grandma burned."

"They exist! A woman in New York has had them this whole time."

I remember how cold the chair felt as I collapsed into it, listening intently as she told me what had happened.

The night before, a woman had left a message for my mother on my parents' answering machine. "My name is Caral Masback, and I was out to dinner with a friend when your mom's name came up. Please call me back." It was around 10 o'clock at night, but my mother picked up the phone.

"I have an amazing story to tell you!" she remembers Caral saying. "My family moved into your house in Scarsdale in 1956," she began, referring to the house Sally sold after Charlie died. "And the house was empty except for one thing that was left behind, and I'd like to give it to you."

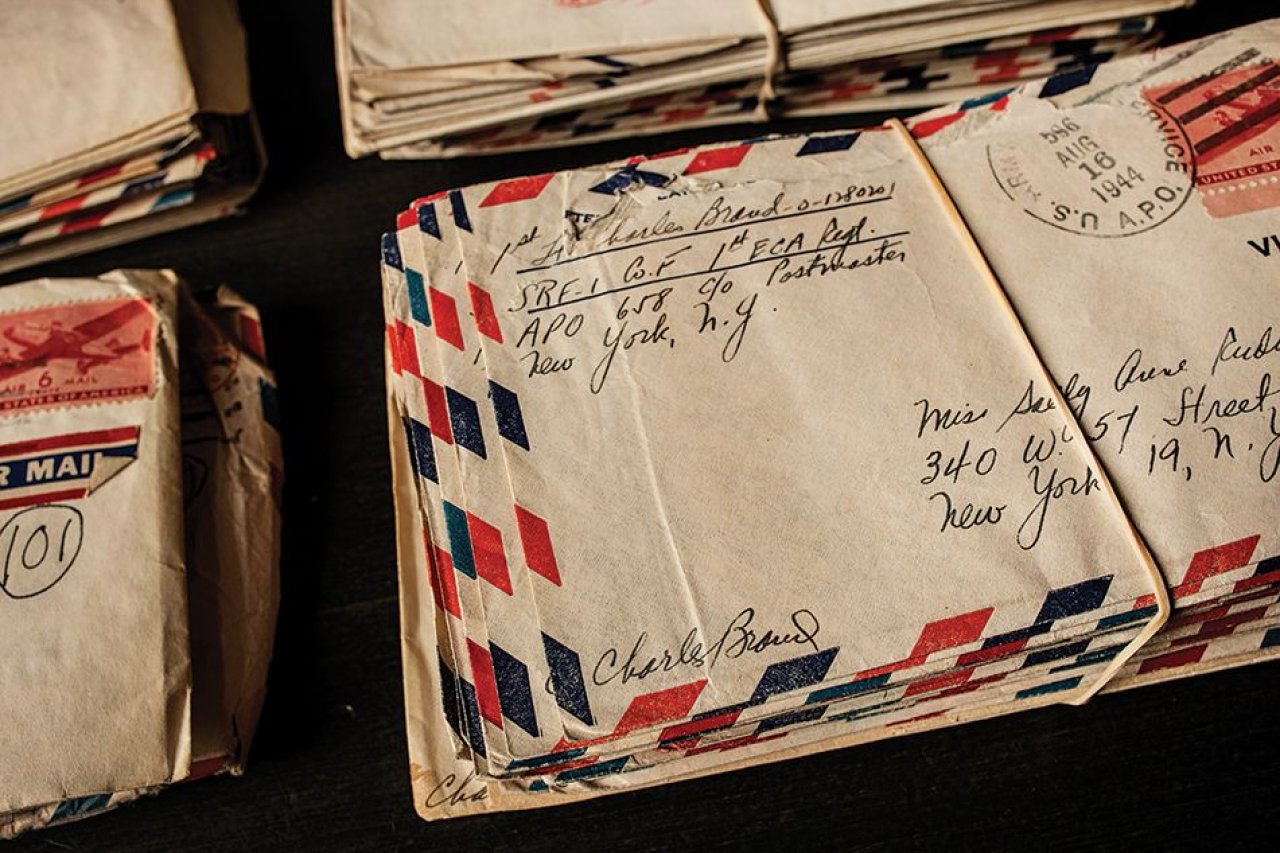

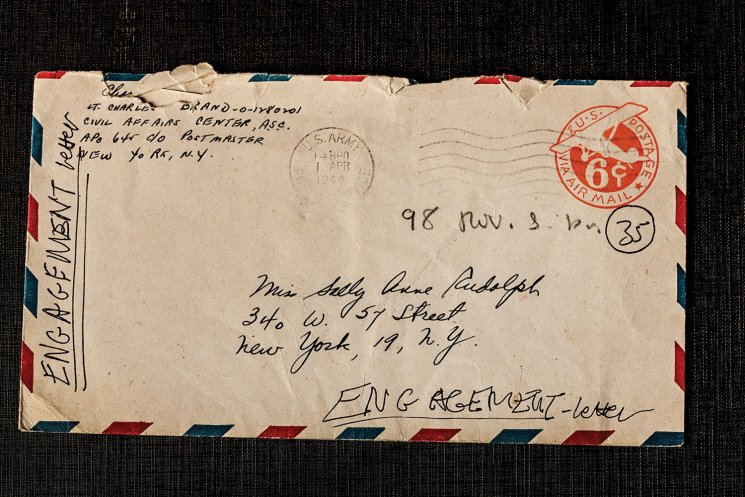

Caral explained that when her family first moved in, the house was bare except for a corner of the attic, where she found, in the dusty shadows, a blue hatbox with a gold braid around the edges. Inside, Caral found hundreds of letters, each one folded neatly inside an envelope, and on the front of each envelope, written in penmanship from a forgotten era, was "Miss Sally Anne Rudolph" and her address at the Parc Vendome.

Caral was 11 years old at the time, and she says that over the next few months, she read every letter in that hatbox in order, oftentimes ignoring her homework to find out what happened next in the love story between this woman named Sally and a man named Charlie. Caral was old enough to grasp the enormity of what she had discovered, but too young to understand why the letters might have been left behind or how to go about finding their owner. And so the letters sat in that attic for decades—until Caral's mother decided to sell the house.

"I had to clean out all of my stuff from my childhood, and I knew that I had to take them. I have no idea why that was so important to me, but it was," recalls Caral, who was in her 30s when her family moved. "I just couldn't leave them."

For the next three decades, Charlie's letters moved with her, but she never read them again. She didn't even tell her husband about them. She kept them close for reasons she can't quite explain. "The letters informed how I thought about longing and absence," she says. "They were also like an unfinished circle. I didn't have any idea how it was going to close—if in fact it would. Because there are circles that don't close."

One spring evening in 2012, Caral went out to dinner with friends. A few of them were older, in their late 80s and early 90s, and during the ride home, they started discussing how rare it was for Jewish women of their generation to have attended Ivy League graduations. One woman casually mentioned that her husband had gone to Cornell, and so had her dear friend Sally Drachman.

"Sally Drachman!" exclaimed Caral, who knew, even as a young girl, that the "Sally Rudolph" on the letters was the "Sally Drachman" who had sold her family their house. "Is she still around?" Caral wondered. When she learned that my grandmother had died a few months earlier, she asked, "Do you know how to get in touch with her children?"

A few weeks after that first phone call, Caral and my mother set up a time to get together. At Caral's house in White Plains, they sat at the picnic table in the backyard, surrounded by trees and flowering bushes and honeybees. My mother says she was numb with anticipation. The chasm between herself and her father had grown so vast that she almost couldn't believe what was about to happen. And then it was happening: Caral placed a few of the letters in her hands, and then a few more, and then she took out a large brown box filled with Charlie's letters. "I was in disbelief and thrilled and just so happy," Ginny says.

"Returning the letters brings a wonderful sense of satisfaction," Caral told me. "It's like a big jigsaw puzzle and you've got the last piece and it's finally complete—the way it should be."

'Darling, What More Can I Do?'

The discovery of Charlie's letters fed a once-insatiable curiosity about a revered family relic we never imagined we would see, touch and read. But it created another beguiling mystery: Why did my grandmother always say she had burned them?

That secret will forever remain untold.

And my family is content to leave it at that, in part because of the incredible gift Caral gave us. Charlie mailed Sally almost 600 letters over two and a half years during World War II. We don't know the exact number he sent, but we do know that she received at least 583 because, in the upper-right corner of each envelope, Sally numbered the letters in the order she received them, writing a "1" or "27" or "501" and then drawing a circle around it. The letters rarely arrived in the order Charlie sent them, thanks to the unpredictability of the mail in wartime, and so Sally's #27 may have been Charlie's #31. All too aware of this lag time, Charlie often quoted from Sally's letters when he wrote his own, and so while we don't have hers, we at least have a sense of what she said.

The scant details my grandmother had shared with us about the letters exploded to life when we started reading them: Charlie was an artful writer, tender, funny and serious—so much like the father my mother remembers in the sliver of memories she has of him. His classic penmanship, in ebony ink, seems to climb across each page at a 45-degree angle, the articulated slope of his lowercase "Rs" and the wide, closed loops on his lowercase "Gs," "Fs" and "Ys." In the beginning, he wrote on personalized stationery, the words "Lieutenant Charles Brand" stamped across the top of each page in bold, blue letters. Later, as the war stretched on and paper grew scarce, he used whatever was available: the Goldsmith Brothers paper Sally mailed him, or single sheets of found paper, as thin as two onion skins, his neat script pushing to the edges of each page, as if he was desperate to fit just a few more words to Sally on every sheet.

Charlie wrote Sally from his desk, from the battlefield and in his tent; even when he suffered from dysentery; even as bombs exploded above his head during a German attack, when he would scribble quickly from his hiding place beneath his cot; even when rain was seeping into his tent. Each day, he wrote to "Dearest Sal," "Darling," "Sweetest Darling" and "Dearest wonderful darling."

Sometimes, weeks would go by without a letter from Sally, and during these periods he often felt overcome by a need he couldn't possibly mitigate. "It's only when I don't receive mail that I realize how dependent I've become on your letters—just like a dope fiend. I'm left with a restless, brooding impatient craving, which I have no means of satisfying. That must be love," he wrote on June 5, 1944, the day before D-Day. Once, Charlie received five of Sally's letters at the same time, but instead of ripping them open immediately, he savored them, opening one letter a day for five days. As he said in the 97th letter Sally received, dated June 19, 1944, "I suddenly realized that if there were no 'you' to come home to, I wouldn't care whether I even came back or not."

Letter #49: April 29, 1944

When I got here [his Army post in England], tired, sunburned—I found—guess what? A letter from you containing that beautiful picture of you. Honestly, I could look at it all day long. There's a fragile quality to your loveliness that reminds me of the Gibson girl…. I got a glassene container for your picture and it's in my wallet. But couldn't I please have a large one for my room—please. A picture like that shouldn't be hiding in a wallet….

Letter #54 - May 4, 1944

Darling, what more can I do to tell you or show you that I love you? I love everything about you—the way you talk, and the way you laugh, and the way you flutter your eyes, and the way you wear décolleté, and the way you get so delightfully happy when you have a drink or two—and the way you write foolish little things in your letters, and then cross them out so you can still read them.… It's close to two in the morning, and I just came in from a night exercise—I'm all in physically, but I knew I couldn't sleep if I didn't write to you.

Letter #412: May 8, 1945

Today is a great day!! I got five letters from you. It's also V-E day.

Letter #500: August 4, 1945

Today started out in a pretty chilly manner—cold, raw—and then I got your July 23 letter—that's where you write, 'But you know, darling, as far as I'm concerned, letters don't satisfy me completely the way they used to. I guess we're victims of a four-letter word spelled time—it has a way of playing funny tricks, like making us slip away from each other after every-so-often.'

Letter #501: August 5, 1945

I'm so lonely, and blue, and dejected, and discouraged tonight—I hardly know what to do.… Darling, we could be having such a wonderful life—I think that as two people, we would be entirely wrapped up in each other—if life would only give us a chance!

Sally and Charlie really were "victims of a four-letter word spelled time." But now, 60 years after his death, that four-letter word has offered up a remarkable, unforeseen gift to my family. During the summer of 2012, my mother sat in her study reading all 583 of Charlie's letters, tears often rolling down her cheeks, a 65-year-old woman meeting the father she never really got to know, looking into the heart and mind of the man with whom her mother fell in love.