It was the week when the world's attitudes towards Russia's leader tipped from wary distrust into frank hostility.

Just six months ago Putin's international standing was at an all-time high as he presided over the Sochi Olympics and released imprisoned oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky and the Pussy Riot group. But it began its precipitous descent with Russia's occupation of Crimea – and now, Putin's name and reputation have become inextricably linked to the tragedy of MH17. This is his Lockerbie moment.

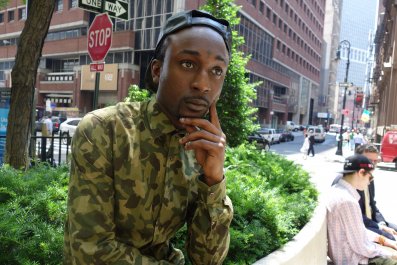

"Politics is about control of the imaginary – and [MH17] plane has become symbolic of something deeper," says Mark Galeotti of New York University. "It is becoming very difficult not to regard Putin's Russia as essentially an aggressive, subversive and destabilising nation after this."

It didn't have to be like this. Unlike Muammar Gadaffi, whose agents knowingly blew up Pan Am flight 103 over the Scottish town of Lockerbie in 1988, killing 243 people, Putin didn't order separatist militiamen near Donetsk to murder civilians. The evidence points to a tragic mistake by ill-trained and ill-disciplined militias to whom Russia rashly supplied deadly surface to air missiles. But the Kremlin didn't have to own this disaster. Putin could have disowned the Donetsk rebel group responsible, agreed to cooperate with international investigators, call world leaders to share their shock and commitment to bring the guilty to justice.

Instead, he did the opposite. In the days after the tragedy the Kremlin obfuscated the facts, blamed Kiev and facilitated the Donetsk separatists' hasty cover-up operations – from attempting to hide bodies that had tell-tale shrapnel wounds to hurriedly evacuating the BUK rocket launcher back across the border (a not-so-secret operation snapped by the camera phones of local residents and Kiev's spies). Putin himself appeared on national television – twice – vaguely blaming the whole incident on Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko for not making peace with the rebels, a convoluted version of a child's "he made me do it" argument. As a result of Putin's KGB-trained instinct to deny everything, the tragedy of MH17 is, in the eyes of much of the world, now seen as Putin's doing.

"For the Western public, Putin has come to occupy the same place as Muammar Gaddafi or Saddam Hussein," says Russian commentator Oleg Kashin, "He's become a kind of Doctor Evil who shoots down planes."

And its not just the public. Western leaders – especially UK Prime Minister David Cameron and his newly-appointed cabinet – have been lining up to blast Putin in terms hitherto used for the likes of Bashar al-Assad and Gaddafi. UK Defence Secretary Michael Fallon accused Putin of "sponsoring terrorism" and told him bluntly to "get out of Ukraine". His colleague, Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond, warned that "Russia risks becoming a pariah state if it does not behave properly". Cameron himself wrote in The Sunday Times that it was time for the West to "fundamentally change our approach" to Russia.

Even Germany's Angela Merkel, whose country is both Russia's biggest business partner and most dependent on Gazprom's oil, called Putin to urge him to use his influence to rein in pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine.

Before MH17, Putin's reputation was, for much of the West, still a matter of debate. For liberals who thought Russia could do much better, he was an autocrat who killed free speech and the Godfather of a pyramid of thieving bureaucrats who had bled Russia dry, killed small businesses and robbed her of an economic future. But for plenty of others – our esteemed colleagues over at Time, for instance, who dubbed Putin their Person of the Year in 2007 – he was a strong leader who rebuilt Russia from its post-Soviet collapse. Social conservatives like former US presidential hopeful Patrick Buchanan admired his stand against gays and Western liberalism, as did European rightwing leaders like France's Marine Le Pen and Britain's Nigel Farage – who in May named Putin as his most admired international leader .

His handling of the Syrian crisis was, in Farage's view, "brilliant". Now, that legion of what the Germans call Putin-versteher – literally Putin-understanders – are notable by their silence.

"Putin apologists are finding it harder to hold their head up, or to be held as credible people," says Galeotti.

There's plenty of opprobrium to go around. Hollywood and the fashion world already turned against the Kremlin in the aftermath of his laws criminalising gay propaganda earlier this year.

But now even Putin's personal friends in showbiz are feeling the heat: 80s action star Steven Segal has found himself disinvited from an event in Estonia for his pro-Putin views.

Putin affects a tough, independent stance. But everything he's done in his 14 years in power has been about building up Russia – and Russia's image in the eyes of the world. From the lavish G8 summit in St Petersburg in 2006 (unlikely to be repeated as Russia was kicked out of the club of leading democratic nations earlier this year), to the $50 billion Sochi Olympics to the 2018 football world cup, Putin has lavished billions on raising Russia's profile.

He's funded institutes in Paris and Washington to boost Russia's influence on policy-making circles, and sponsored no-expense-spared annual conferences for foreign Russia experts from around the world in order to convince academics and commentators of the wisdom of the Kremlin's line.

MH17 – or rather, the Kremlin's handing of its aftermath, has ruined years of careful soft-power building at a stroke. For someone as status-obsessed as Putin, that must hurt.

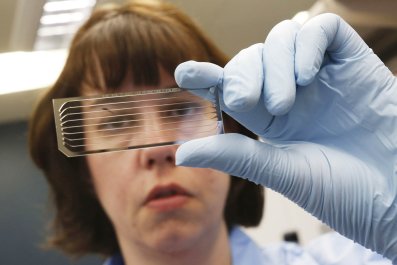

Unfortunately for Russia, public-relations disasters on this scale have real-world consequences. Just hours before MH17 was blown out of the sky, the US announced a new round of economic sanctions, this time targeting Russian oil companies' ability to raise financing on international markets.

After MH17, pressure has grown exponentially to tighten sanctions even more – a move which could bring Russia's economy to its knees in short order.

"The threat of sanctions against entire sectors of the economy is now very real and there are serious grounds for business to be afraid," Putin's first prime minister Mikhail Kasyanov told Bloomberg after the crash. "If there are sanctions against the entire financial sector, the economy will collapse in six months."

Realistically, though, there's no way that Europe can economically disengage from Russia – especially as the continent relies on the state-owned gas giant Gazprom for 25% of its energy needs. If only for pragmatic reasons, Europe will have to continue to deal with Putin. But long-term, its clear that MH17 will accelerate the search of non-Russian energy sources and harden opposition to Gazprom super projects like the South Stream pipeline from Russia to Central Europe.

But the most important short term consequence will be to crystallise a virtual iron curtain between Europe and Russia.

"There will be a much clearer sense of a borderline and the need to defend that border – from the Baltics to Ukraine," says Galeotti. In practical terms, that means that Europe will have to help Ukraine defeat pro-Russian rebels. "The explosion of the [MH17] missile propelled Kiev into the bosom of Europe. The best way to show Putin that aggression doesn't pay will be to support Poroshenko."

On the ground, it's also likely that the pro-Russian rebels' MH17 debacle will hasten their defeat. Kiev will be emboldened to pile in and finish them off – and with the world's eyes on the conflict zone, it will be much harder for Russia to continue to supply the kind of heavy weaponry such as planes and rocket systems that the rebels need to make a real tactical difference.

That in turn puts Russia in a trap of its own making. "The popular view [of the Donetsk separatists] is that Putin has let a genie out of its bottle which will eventually eat him," writes Kashin. When they are eventually defeated by Ukrainian forces, "Russian volunteers will come back from Donbass and knock on the doors of the Kremlin itself." Yet if Putin continues to support the rebels he faces worse international sanctions.

For most of his reign, Putin has been lucky. Early in his tenure oil jumped from $19 a barrel to $100 and stayed there. Chechen rebels turned on each other and brought their longstanding insurgency to a bloody end. Political opponents realised it was far better to join the Kremlin gravy train rather that fight it. But now his luck has run out, and he's floundering.

"Bad things happen" – as former Ukrainian Leonid Kuchma feebly responded when his forces accidentally shot down a Russian civilian airliner in 2001. They do. But Putin has allowed himself to become a hostage to bad stuff happening, which is just bad politics. Cover-ups rarely work , as the US found in the aftermath of abuses at Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad, for instance, or the shooting down of an Iranian civilian airliner over the Persian Gulf in 1988, just five months before Lockerbie, the smartest way to deal with such disasters is to accept, apologise, punish the guilty.

This year Putin gained Crimea – but also irrevocably lost Ukraine, which is far more strategically important.

And after his mishandling of MH17, he's blundered into losing the last shreds of international respect too. That was an unnecessary mistake which will cost him – and Russia – dearly.