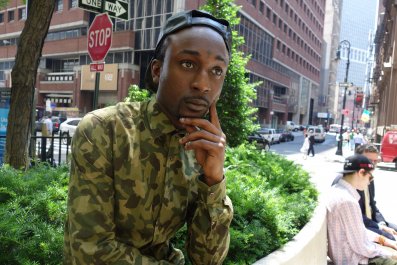

Thinner than average, with serious, shadowed eyes, Kevin Anderson, 36, has worked as a filmmaker for over 10 years. He's traveled throughout Europe and the Americas producing web and sports videos, news packages and documentary shorts. In his infancy, he was diagnosed with a rare genetic disease, phenylketonuria (commonly referred to as PKU), where the body cannot properly break down protein. Throughout his life, he has taken medicine and followed a special low-protein diet, but other than these restrictions he enjoys a healthy life.

Recently, though, he "stumbled across this video that showed people with undiagnosed PKU." While he had often heard stories about what would happen if he had never treated his condition, "I'd never seen pictures of it, I'd never encountered it myself, so it just wasn't quite real to me," he says. "And when I watched that video.… " He trails off, choking up, pausing until the heartbreak passes. "It just captured me. I had the sudden realization I would have become mentally retarded; I would have been in an institution if it hadn't been for newborn screening."

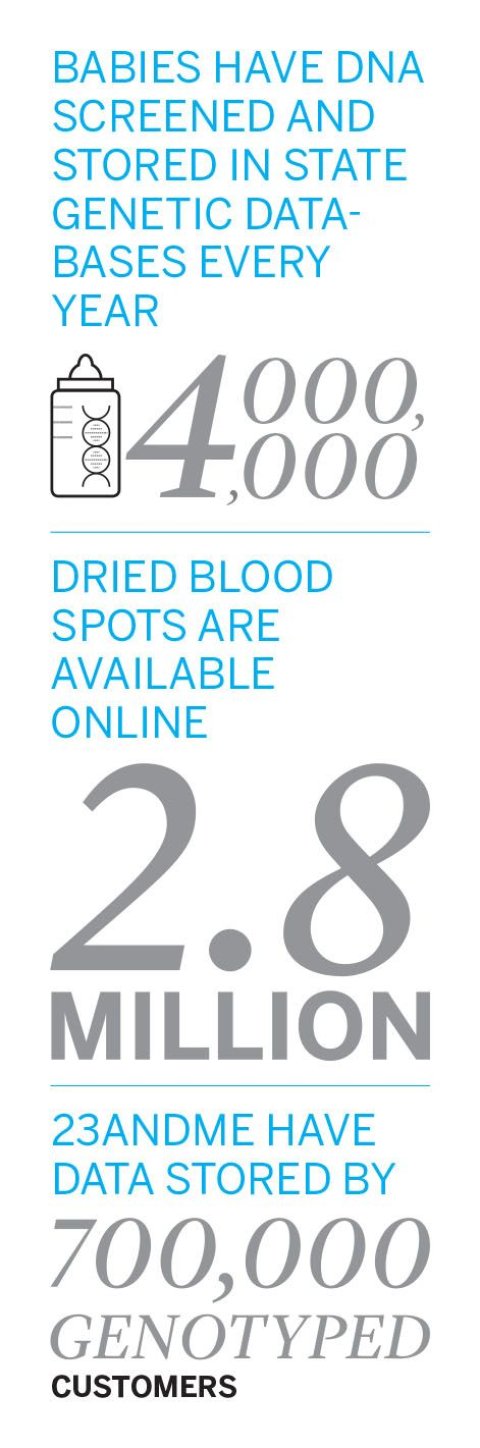

Every year, approximately 4 million newborns in the U.S. are screened for congenital disorders, and about 12,500 of these infants are diagnosed with an inherited condition. Many of these disorders (like PKU) can be effectively treated when caught early, allowing an infant to grow and develop normally. By every account, newborn screening is one of modernity's biggest medical success stories—yet most of us are not familiar with this compelling tale or even know that we most likely have been screened.

That's the good news. The bad news is that we also may not be aware that many states have created biobanks funded by genetic material left over from our screening tests, and, even more surprising, our specimens may be used for purposes we do not fully understand or for which we have not granted informed consent.

Blood Spots

Massachusetts began the original newborn screening program back in 1963 with a test for PKU. Though few babies were found to have the condition, the benefit of an early diagnosis was so great that other states soon instituted screening programs. Once they'd adopted the practice, states expanded their scope and began testing for more conditions. Ten years ago, 46 states were screening for just six conditions; now all 50 states and the District of Columbia routinely screen newborns for at least 30 genetic conditions, with some states testing for nearly twice that number.

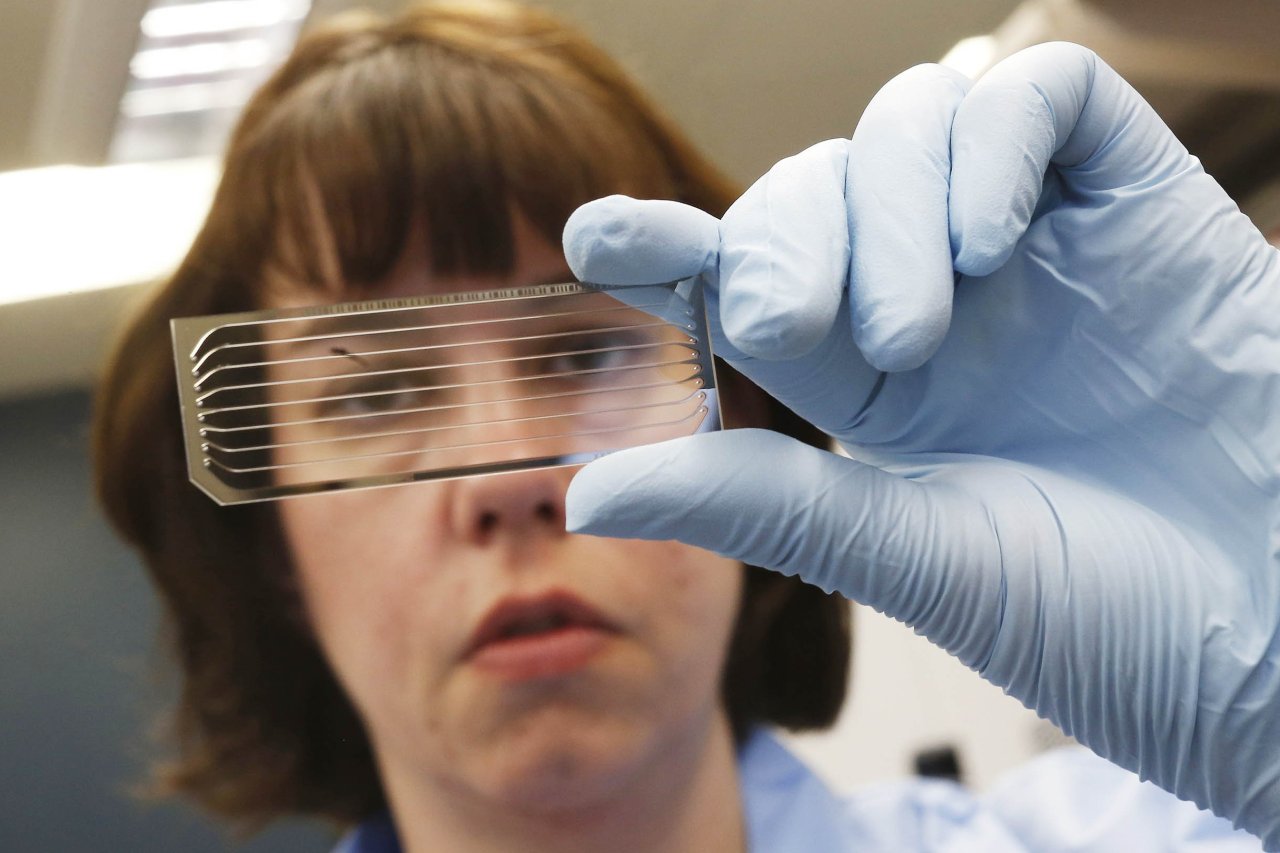

Though each state runs its own program, they all begin by collecting a blood spot from the heel of a newborn infant. The sample is analyzed; results are returned. Commonly, the screening program is first mentioned when a mother has checked into the hospital for delivery, and, generally, the programs are mandatory under state law.

That this information comes so late in the game is a "long-standing issue and a controversy to a certain extent in the newborn screening field," says Dr. Jeffrey Botkin of the Secretary's Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children, which advises the Department of Health and Human Services on newborn screening. In the 1960s when the program was first developed, "the feeling was, the advantages for newborn screening were so compelling, it was appropriate or acceptable to have states simply mandate screening," he says. Now 43 states allow parents to decline the screening process based on religious beliefs or philosophical reasons. Rarely, though, is that option exercised. Some believe the reason is that most parents only hear about the program in the hectic period after a mother in labor enters the hospital.

"These newborn screening DNA databases make a complete mockery of informed consent," Jeremy Gruber, president of the Council for Responsible Genetics, tells Newsweek. "What people also don't know…is that this is the one test that is not done by the hospital or a third party on behalf of the hospital.… It is done by the state department of public health."

In most states, blood spots are transferred to long-term-storage banks run by state departments of health, where they are retained for at least a couple of years. But in 12 states, samples are kept in a biobank for 21 years or longer. That's because, increasingly, health departments are using—and sharing—the genetic information for research and analysis. This practice has accelerated since 2009, when the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded a contract to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) to establish a Newborn Screening Translational Research Network and develop a national repository of newborn DNA "stored by state newborn screening programs and other resources." Meanwhile California, Iowa, Michigan and New York already participate in a virtual repository, which allows researchers to access data—and in some cases the stored infant blood spots themselves—for their investigations.

This expansion of the newborn screening programs will continue to create new opportunities for big research ventures. As DNA sequencing becomes cheaper and more accessible, many predict whole genome sequencing will replace the current blood spot tests. According to ACMG Executive Director Michael S. Watson, the NIH has already awarded research grants to explore the feasibility of integrating whole genome sequencing into newborn screening.

Monetizing the Human Genome

It has been more than a decade since the human genome was first sequenced, and every week, it seems, there's new research identifying a mutation to predict some dread disease. It is now understood, for example, that variations of the APoE gene may increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease and that the BRCA gene mutation may double the risk of breast cancer.

In many cases, though, it's still unclear how one genetic mutation might affect a person's health. Scientists will need lots and lots of DNA samples to translate the wealth of information found in any one genome—it is only by comparison that they can understand how, when and which genes matter, separate from the environment. Current efforts at genetic analysis are plagued by a lot of noise and uncertainty.

For instance, 23andMe, a consumer genetics company, will genotype your DNA and provide you with ancestry-related reports and raw data. Previously, 23andMe's reports included odds ratios for certain medical conditions. But in November 2013, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited the company from continuing to sell health reports, as they could not be "analytically or clinically validated." (The FDA's approval process for these reports is ongoing.)

In reality, a health report may just be the most enticing carrot 23andMe was able to dream up in order to get your DNA in its computers. As noted by the authors of an article in The New England Journal of Medicine, "23andMe has...suggested that its longer-range goal is to collect a massive biobank of genetic information that can be used and sold for medical research and could also lead to patentable discoveries." This characterization is not denied by 23andMe, which tells Newsweek, "The primary mission of our company is to accelerate genetic discovery."

The real money, then, isn't selling you a health analysis; it's in using and selling your data for biomedical research.

It's not much different from how Google, Yahoo and Facebook give us search engines, email and social networking for free, only to sell all the information they gather to anyone wishing to market products to us. 23andMe has already conducted research funded by the NIH and collaborated with academic and industry partners. The company offers customers who buy personal genetic reports the option to participate in its wider research program. Currently, 23andMe stores data from more than 700,000 genotyped customers, and of these, more than 80 percent have not only opted into the research program but have also actively answered survey questions.

"The way information becomes really valuable is when we can start to look at genetic information and also understand phenotypic data," explains a company representative. Research looks something like this: After first isolating all their customers who have stated on a survey that they have a particular allergy—say, a cat allergy—a researcher might run a query to see if these customers share some genetic mutation, and with further analysis find out where those variants are located in the DNA. "Those are the things we want to explore," 23andMe says. "But we can only do that if you answer questions." Participation in biomedical research, then, really has two parts: consenting to use of your genetic data and providing your personal information to enhance the value of that data.

The company's privacy policy states it cannot share individual-level data with third parties without a customer's explicit permission. Consent only enables company researchers "to look at the de-identified genetic data in the aggregate," 23andMe says.

The Illusion of Anonymous Information

The state screening programs and the Newborn Screening Translational Research Network also de-identify newborn baby blood spots before loaning them out to researchers, but so far truly anonymizing DNA has proved impossible.

"Right now we don't know a way to guarantee anonymity from the technical aspect," says Yaniv Ehrlich, a computational biologist at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Famously, Ehrlich and his colleagues published a paper showing how they discovered the (supposedly hidden) identities of participants in genetic research studies by cross-referencing their data with publicly available information. A clever academic stunt, sure, but one that also revealed an uncomfortable truth and made many people question the possibility of privacy in the genomic era.

Some protections regarding genetic privacy do exist. The Genetic Information and Non-Discrimination Act (GINA), which became law in 2008, prohibits health insurance companies from using genetic information to make eligibility, coverage or premium-setting decisions. The law also prevents employers from including genetic data in their decisions about hiring, firing and promotions. However, GINA has gaps. For instance, the law does not apply to companies with fewer than 15 employees or the U.S. military. And it also does not cover long-term care insurance, life insurance or disability insurance; for instance, having discovered you have the BRCA gene that raises your risk for breast cancer, a company can legally deny you a life insurance policy.

Botkin argues "there's no motivation" for anyone to re-identify DNA and cross-reference it with public sources. "Why would anyone want to take the time and effort?" he says, adding, that so far "there are no examples of cases in which bio-specimens have been used in an unethical manner leading to individual harm."

Watson offers a different perspective on the matter. "It just amazes me what people will put into social network and media about themselves and then be worried about the privacy of the exact same information in another context," he says. "They don't appreciate how easy it is to link across these things." He and his colleagues have built barriers into the Newborn Screening Translational Research Network to prevent anyone from doing "this type of linkage" across databases.

Nevertheless, your DNA is a treasure trove of personal information, including your eye and hair color, paternity and health. Gruber likens it to a file cabinet containing your most secret documents, except with DNA it's more as if you are walking around with these documents and "anyone with the proper tools can now open your filing cabinet and find out about you," he says. The fact is, you shed DNA daily, in countless public places, and though you probably instinctively feel your DNA and sequenced genome is yours, you have no real ownership rights—especially once your DNA has been entered into a biobank.

Who Owns Your DNA?

Science magazine drew a very pointed analogy between genetic data banks and money banks in an article published earlier this year. As a bank account holder, you get a receipt when you deposit money. Later, you can access your account, and even terminate your relationship with the bank if you choose. "When we make a deposit to a data bank or biorepository, in contrast, putting our data or specimen into the hands of researchers or clinicians, we lose track of it," the authors write, further noting how "a deposit to a research or clinical repository is a one-way transaction in which we give up most of our agency and control."

Currently, the legal right to retain and use dried blood spots is determined by each state. While Oklahoma prohibits the use of dried blood spots for public health purposes, including research, without express parental consent, four other states declare the spots state property. Though rules are clear, Pediatricsreported, some states "may be acting outside the scope of their legal authority."

Arguably, this was the case in 2008, when five families sued both the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) and Texas A&M University for using stored blood spots for undisclosed research purposes without parental permission. Previously, Texas had destroyed samples soon after newborn screening, but the state changed its rules in 2002 without notifying parents and began donating stored samples to researchers. In the lawsuit, the Texas Civil Rights Project claimed using blood spots in this way went beyond the purposes of the newborn screening program and violated parents' rights under the Fourth Amendment, which protects against "unreasonable searches and seizures" by the government. (Texas A&M declined to comment.) The case was settled out of court, with the DSHS required, as part of the agreement, to list on its website all the research projects to which blood spots had been sent.

It came out, then, that the DSHS had loaned blood spots to (and been "appropriately reimbursed" by) pharmaceutical companies, while also lending 800 blood spots to a lab run by the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology to help get its new forensic database up and running. The 800 spots were used to establish general reference points of variation among different ethnic groups. A representative explained that the DSHS provided de-identified blood spots "because we believed it was an important research project, and the information we agreed to provide in no way could be linked to a particular person."

Nevertheless, once again the Texas Civil Rights Project filed a lawsuit, this time claiming the DSHS acted unlawfully and with deception when it sold, traded and distributed infant blood samples collected without consent between 2003 and 2009. The judge dismissed the case when none of the families named in the lawsuit were found to have unknowingly contributed to the pathology lab, says James Harrington, the lawyer who represented the families.

However, as a consequence of all the publicity, Texas destroyed millions of samples still stored in its biobank and enacted a new law in 2012 for its newborn screening program. "Now they ask people if they want to opt in, and they have to disclose if they're giving it to someone else, a pharmaceutical company, whatever," Harrington says.

Other states may soon be grappling with some of these same issues. Recently, Indiana learned how its Department of Health has stored blood samples from babies born since 1991 for possible use in medical research, all without parental permission.

Botkin says that people are "generally stunned" to learn the states are saving infant blood spots left over from the screen tests. And yet, when explanations are offered, the use of the blood spots clarified, the research oversight mechanisms explained, people are reassured, and the "vast majority" are supportive of state programs retaining and using specimens.

But maybe they shouldn't be. Currently, there are private commercial data banks, including those run by health care companies; biobanks under the auspices of the NIH, academic and private research institutions; and the FBI's Combined DNA Index System, routinely used for law enforcement purposes. Gruber says as genetic biobanks "become more widespread and the uses for DNA become more common…we're going to start to see more and more bleed-over of these databases." Your child's DNA, then, might easily move out of the state newborn databases and into research programs where it might be used for purposes you never intended, or even imagined.

Correction, July 28th, 2014: An earlier version of this article stated that the FDA sent a warning letter too 23andMe in December, 2013. It was actually sent in November of 2013.