Michael Vickers's ranch 113 kilometres north of the US–Mexico border in Brooks County, Texas, is near a Border Patrol checkpoint. Undocumented migrants trek through the harsh brushland onto his property to avoid capture. An electric fence encloses the nearly 1,000 acres: at 220 volts, says Vickers, a local veterinarian and avid hunter, "it won't kill them but it will make them wet their pants".

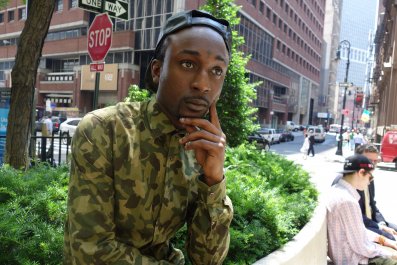

In 2006, Vickers and his wife Linda founded the Texas Border Volunteers, which now has some 300 recruits, who dress in fatigues and patrol private ranches in South Texas, using night-vision goggles and thermal imaging to track people in the dark. When they spot migrants they alert the Border Patrol. Former volunteers say the Vickerses did not allow them to provide first aid to migrants in distress or get closer than 10m. If a migrant was severely dehydrated, they were allowed to throw a bottle of water from that distance.

In her home, Linda dispenses a glass of strawberry, cucumber and mint-infused water, moving swiftly around the kitchen in her workout shorts, beige vest and calf-high cowboy boots. In a nearby hallway, a plaque hangs on the wall: "2012 Super Star Award Presented to the B.E.S.T. Team – 119 Reported Illegal Aliens, 101 Border Patrol Apprehensions". The plaque honours Linda's dogs, Blitz, Elsa, Schatten and Tinkerbell, three of them German Shepherds, who have been trained to sniff out migrants and to whom she speaks lovingly in basic German. "You can't hide from that nose," says Linda.

Linda, chief of staff for the Texas Border Volunteers, says she frequently sees undocumented migrants near the house. But she is not afraid. She is always armed with a .45 Long Colt – the kind of gun used to shoot ducks, her husband says. Her job, she says, brings her enormous satisfaction. "It makes you feel good when Border Patrol loads up a group that you've reported," she says.

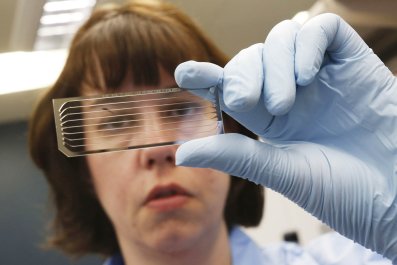

Brooks County garnered national attention in June after the remains of dozens of unidentified migrants were discovered buried at a local cemetery in milk crates and plastic bags. The county has the highest number of migrant deaths in Texas – 129 in 2012, 87 in 2013, and 41 this year so far, with many more expected during the scorching summer months. It is home to one of Border Patrol's busiest checkpoints. "In a sense, what we have is two borders," says Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith, coordinator of the University of Arizona's Binational Migration Institute. "We have one real border and then the border that has been set up by checkpoints."

President Barack Obama is under growing political pressure over a recent flood of child migrants from Central America, driven by rumours that his administration is more welcoming than past ones. Obama has asked Congress for $3.7 billion in emergency funds to help deal with the crisis, while Texas Governor Rick Perry has asked for National Guard troops to be sent to the border. One of Obama's top campaign promises was to pass a comprehensive immigration reform bill, but his efforts have so far produced very little. While Congress is deadlocked, with conservative Republicans rejecting anything but a tough crackdown on people crossing illegally into the US, Americans in border states and beyond are becoming increasingly polarised.

Texas is especially divided. Demographically it is developing as a more Hispanic state, opening up the prospect of Democrats making gains there if they can present themselves as more sympathetic to the concerns of immigrants. At the same time, residents such as the Vickerses are dealing first-hand with the problems caused by the influx of undocumented immigrants.

The migrants who make it as far as Brooks County tend to be adults, since minors who cross the border will often give themselves up to US authorities, trusting that they will not immediately be deported. Ranchers in Brooks County complain of property damage and trash left behind by the migrants, referred to more often than not as "illegals" or "wetbacks".

One day in early July, two men and two women from Guatemala who looked to be in their late teens were spotted and reported to Border Patrol. Their eyes were sunken, their skin scorched by the relentless sun that had worn them down as they walked for three days in 100-degree heat. When the agents arrived, the four looked resigned, walking over and sitting down in the small triangle of shade offered by the Border Patrol SUV.

Down the road, a woman sauntered near the entrance of a ranch, her military green T-shirt hugging her plump curves and blending into the background. BJ, as the 53-year-old requested to be called, manages several large ranches in Brooks County, population 7,237. She said she had seen the migrants walking by on the highway and notified Border Patrol.

"I will do everything in my power to send them back," she says, sitting down at a wooden picnic table near the house. Ranchers like BJ see themselves as the first line of defence against migrants. Before calling "the boys", as she refers to the Border Patrol agents who make up the vast majority of her social circle, BJ says she goes on a "manhunt".

"It's a cat-and-mouse game," she says with a grin, driving through ranch trails. She starts by looking for footprints – they are most noticeable on the sand tracks she has set up next to the trails which she smooths by dragging tires. When she sees a fresh set, she speeds through the trails, finds the migrants, chases after them until they tire out, corners them and then yells, "Pa'bajo!" – Spanish for "down".

What if they resist? She smiles and says that is one question too many. Her Heckler & Koch P2000 pistol rests in the cup holder next to her right knee. "You can't tell me this isn't fun," she says, chewing dipping tobacco and spitting its juice out into an empty plastic water bottle, "more fun than shopping and looking at sights." As she came up to a yellow road sign that read "Caution", she pointed out the figures of running people she had drawn on it to make her friends laugh.

From October to May this year, 323,675 people have been apprehended along the southwest border, a 15% increase as compared to the fiscal year 2013, according to the US Border Patrol. More than 52,000 of these are unaccompanied minors from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, fleeing widespread drug-related violence in the region and drawn by rumours of amnesty in the US.

Overwhelmed, Border Patrol agents along the Rio Grande Valley have been handing some of these migrants a bus ticket to their final destination along with an immigration court citation. But for those who continue on their way north via US 281, the longest continuous highway in the country, the journey through southern Texas can be more treacherous than the border itself.

Some 16km north of the Vickers ranch is Falfurrias, Texas, the largest city in Brooks County, home to the South Texas Human Rights Center. It is run almost single-handedly by Eduardo Canales, a 66-year-old who has raised some $12,000 in private donations since last August.

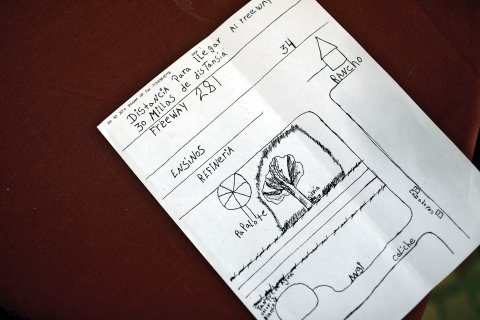

Canales is hunched over a simple black-and-white map he received via fax from a man whose sister did not survive the journey. US 281 is shown on the top, rudimentary sketches of a ranch, windmill, water tank and hunter's stations below it. In the middle, just above carefully drawn barbed wire, a tree. Next to it, a stick figure with the name, Silvia.

"To get a map like that, it's very rare," says Canales, marvelling at its detail. Silvia's brother had convinced one of the people who had been travelling with her before the group left her behind to draw it and then sent it to Canales.

Canales made a few calls to the sheriff's office, trying to assemble a team to find Silvia's remains. But everyone was waiting for Border Patrol to get permission to enter the ranch identified in the map. Most ranchers have given Border Control a key or code to their gates, but almost everyone involved in rescues and apprehensions abides by a "ranch etiquette" and calls the property owner before they enter.

Looking defeated, Canales sat slumped on his office chair. "We have to go through so many hoops to save a life," he says. His office contains a stack of blue plastic barrels with "Agua," painted on them in white. One of his current projects is convincing ranchers to put these water stations on their property. The stations are simple and mobile, the barrels filled with gallon jugs of water that migrants can stealthily pick out and take with them.

It has been a struggle: among others, BJ and the Vickerses have declined to put water stations on their ranches, saying that that would make it too convenient for migrants. In any case, says Vickers, the windmills provide a water source which is safe for cattle, and therefore for migrants. Some ranchers have acquiesced. County Judge Raul M Ramirez is one of them. He is familiar with the despair that death brings to the families of deceased migrants. Ramirez is often called out to pronounce migrants dead.

Kass Hernandez, one of the youngest ranch owners in Brooks, allowed Canales to put two water stations on his property. Hernandez is perpetually angry about the property damage and trash that migrants leave behind – he walks a few feet next to the fence, picking up sweaters, aspirin bottles and water jugs, visibly upset. But, "we put water stations because it is the humane thing to do," he says, surveying the cut barbed wire.

Hernandez has placed several ladders against the fence in the hopes that migrants will stop cutting it but says he still has sustained around $80,000 worth of damage.

When he sees several migrants together, he calls Border Patrol. "It's like a dog taking a crap on your front lawn," he says of the groups. But he says he feels compassion for stragglers, the ones that are too weak to keep up or too sick to keep going. If one comes knocking at his door, Hernandez says, he invites the person in, sharing whatever he is having for dinner, and letting them make a phone call to loved ones back home. He appreciates the company, says Hernandez, but never lets his guard down. He pulls out an Uzi and a .380 pistol from behind the kitchen cabinets and an assault rifle from a closet and lays them on the kitchen island.

Most residents here have found common ground on one issue: the need to convince Washington to designate Brooks County a border county, a move that would help secure federal resources destined for border security. It costs the county around $2,250 to handle each migrant death, and such costs have put an added strain on a local economy already hit by dwindling oil and gas revenues. Last year, the county cut health benefits and pay for its employees.

"We have a humanitarian crisis but we also have a humanitarian cost," says Urbino Martinez, chief deputy of the Brooks County Sheriff Office. He estimates that between 300 and 500 migrants go through the Brooks County brushland on any given day.

What the county needs, according to Martinez, is "more action and less talking. Forget the blue coats or the red coats or the independents." As Washington stalls on the immigration issue, Brooks County pays a heavy price, he adds. Five years ago, Martinez adds, his office had 10 full-time deputies; now he has four.

Back at the Vickers ranch, Linda's dogs waded in one of the windmill water pools, clumps of algae floating on its reddish surface.

As dusk set over the expansive brush, Vickers drove his all-terrain vehicle in silence through the zigzagging trails. Then, suddenly, he stopped and reached down for his binoculars. He held them up to his squinting eyes for several seconds, a look of admiration on his face. A deer stared back in surprise and then, in a flash, pranced off into the brush.