Back in the 1980s, I was working in a bookstore across from a movie theater in San Francisco, arguing with a bunch of other marginally employed English lit graduates. When things got slow—when tourists weren't buying stacks of postcards and the latest Ludlum novel—it was easy to start a debate by talking about movie critics. Not the movies themselves, mind you, but the people who reviewed them. Sarris versus Kael, for instance—an oversimplified debate about the relative merits of The Village Voice's Andrew Sarris (he of the "auteur theory" that held a director was as responsible for a film as an author was of his book) and the California provocateur Pauline Kael (who championed the importance of collaborators and found Sarris rather stuffy and square). For most moviegoers who came in, killing time before the next screening, it was angels-on-the-head-of-a-pin stuff that had nothing to do with the possibly cathartic but more often disappointing experience of seeing things blow up and then made right in under 120 minutes.

And for those who made the mistake of asking us how many stars a given movie had, or whether Siskel and Ebert had given it their signature thumbs up or down, we had no time. Take your remaindered cat calendar and let us go back to pretending we're French.

In light of a new documentary about Roger Ebert (Life Itself, in theaters and on demand), the days when people cared about critics, any critics, seem halcyon indeed. And the loss of Ebert and his longtime adversary and critical partner, Gene Siskel, is not the problem. "The reality is that when Siskel and Ebert were on TV, film was a part of the cultural conversation in a very different way," says Stephanie Zacharek, who reviews films for the Voice today. "It was like everybody talked about a film and it would be around for a couple of weeks. If you didn't see Kramer vs. Kramer the week it opened, you'd see it two weeks later, you'd go to a dinner party and talk about it. Things would just linger a little bit longer."

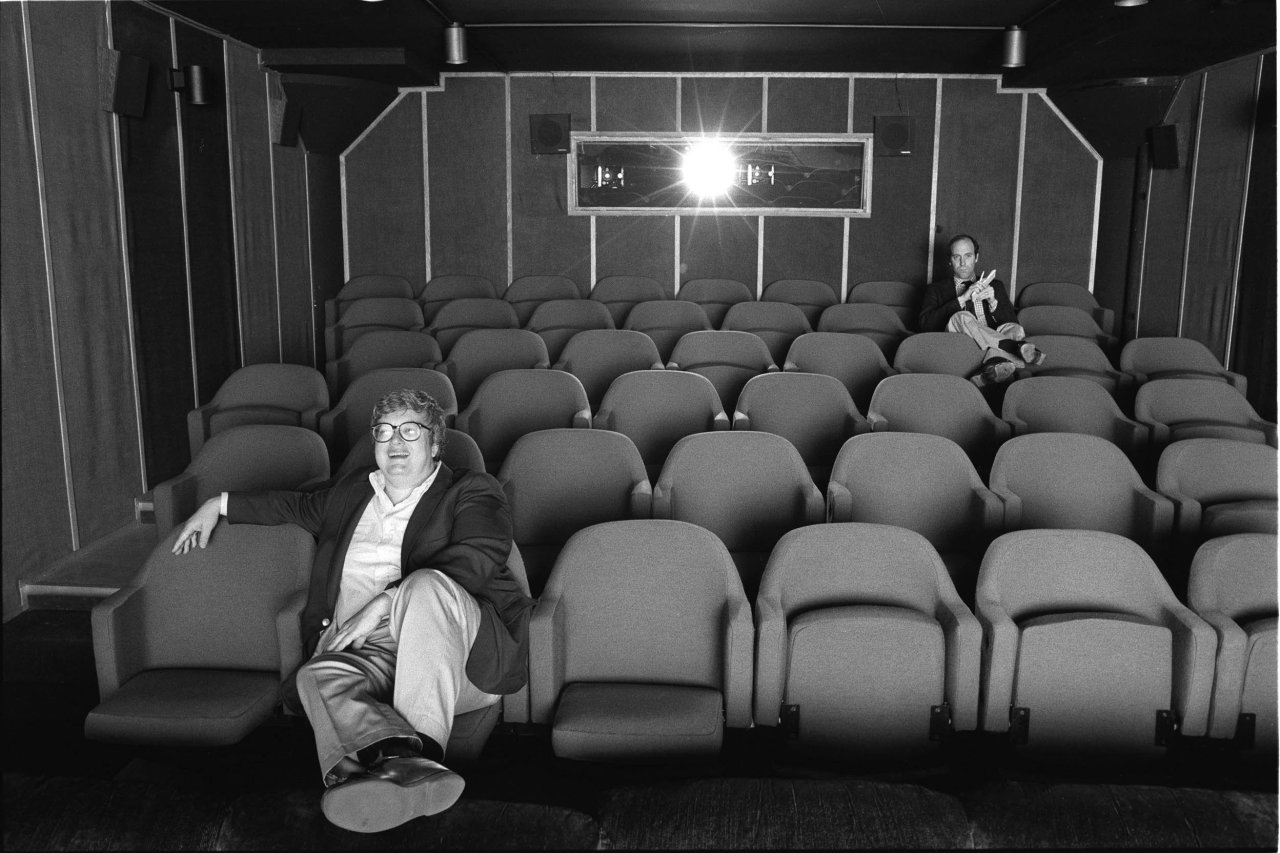

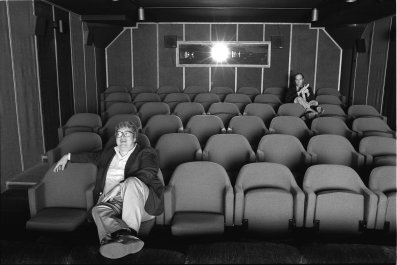

If snobs like us hated Siskel and Ebert (whose show, under various titles—Sneak Previews, At the Movies—ran on public television and then in syndication for over 20 years), it was because it made film appreciation too simple, we'd say—too black-and-white, good-or-bad, up-or-down. "This was not Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael," The New York Times's A.O. Scott says of their debates in the documentary, and he means that as a compliment. He calls Ebert "the definitive mainstream film critic," and as someone assigned with the unenviable task of telling millions of Times readers whether they should waste money on a babysitter, Scott may have inherited that mantle (as opposed to the paper's more unabashedly intellectual and generally amusing Manohla Dargis).

Ebert, who died of complications due to cancer in 2013 at the age of 70, was the product of the print age. He began working on his local paper at the age of 15, ran the student newspaper at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and was writing for the Chicago Sun-Times in the 1960s as American film began to get interesting again. "Pitilessly cruel" and "astonishingly beautiful" was how he characterized Bonnie and Clyde (1967)—a film that became a bellwether for critics. Kael, who was writing for The New Yorker by then, offended some of the magazine's readers with her enthusiasm for the movie's lyrical violence, and Newsweek's Joe Morgenstern famously panned the flick—and then changed his mind and came back to write a second appreciative review a week later.

"Roger could knock out a full movie review in 30 minutes," an admiring colleague says in Life Itself, and it's that facility that made some more long-winded critics of the time suspicious. How could he be any good if it's that easy? they wondered (funny how no one said that about James Agee), but Ebert had the last laugh when he became the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize, in 1975.

That speed and fluency left him time to do other things (quitting drinking in 1979 did too, and he would later publicly admit to his alcoholism)—including encouraging young writers. I was covering the media for Salon, sometimes writing about movie criticism, when I got my first email from Ebert, and he continued to ping me over the years, even offering to help me find a job when I was laid off (provided I wanted to work in Chicago). I later learned he did that for a lot of people—championed their work, encouraged them to keep going—as the Internet made critics more and more superfluous.

"There's some talk inLife Itself about how Roger 'democratized' criticism, and I take a little issue with that," says Glenn Kenny, the former Premiere critic who now writes for Ebert's site. "I think he'd be the last to agree with the digital Panglosses who rejoice in the Internet's 'everyone's a critic' frontier. But Roger was a great appreciator of critics, good critics with strong individual voices. I actually read Roger after I'd seen him on television; in the wilds of New Jersey, where I grew up, access to the Chicago Sun-Times was scarce. But once I did get around to reading him, his work affected me by example, the example being his strong, consistent, entirely individual voice."

Ebert used the platform of his reviews and later the show to champion new directors. "I believe I would not have a career if not for these guys," says Errol Morris, whose pet cemetery documentaryGates of Heaven (1978) was given the spotlight by Siskel and Ebert. Martin Scorsese, an executive producer of Life Itself, recalls Ebert's excitement for his first feature, Who's That Knocking on My Door (a.k.a. I Call First, 1967)—and the spanking he received for The Hustler sequel The Color of Money (1986). He claims that a retrospective of his films the duo gave him when he was at a low point in the 1980s revived his career, and Life Itself director Steve James (Hoop Dreams) lists Ebert as a benefactor. Who has that much influence today?

An early adapter to the web, Ebert wrote reviews that are probably more widely read now than they were in his lifetime. RogerEbert.com is a showcase for his reviews and books, going back to 1967. It was like a monument in advance, painstakingly built by the critic, his wife Chaz (the not-so-secret hero of the film) and the digital entrepreneur Josh Golden. As cancer claimed his throat and lower jaw, "my blog became my voice," and as he came to speak with the aid of a computer, so his site (which also hosts the voices of dozens of critics and film reporters) became an extension of the man. Time critic Richard Corliss, who famously attacked the Siskel & Ebert show, and the tyranny of the thumbs, in a 1990 Film Comment essay, came to be an admirer.

"His voice was stilled, but he's talking more than ever," he says.