The Gaza Strip, one of the most densely populated places in the world, is a dreadful, sorrowful place. Even when it is not the subject of a full-frontal Israeli assault, it is a sea of desperation for its 1.7 million residents, half of whom are children.

The toll of the current war has already been horrific. According to UNICEF, 59 Palestinian children—43 boys and 16 girls—were killed in the first nine days of the conflict, before the Israeli ground assault began. Most were under the age of 12.

"That means an average of four children a day," says Bruce Grant, the chief child protection officer at UNICEF in Gaza. "It means for every two militants killed, three Palestinian children are killed. It means the kids are paying a deadly price."

Eleven more children were killed on the night the Israeli ground assault began, including a 5-month-old baby. "When you look at the number of children killed and injured, and their houses destroyed. When you add that up," says Grant, "it's roughly 58,000 children who are going to be in need of urgent psychosocial support."

These children need to return to some form of normality as soon as possible, Grant says, because they have either lost a sibling, their home was bombed, or they are displaced.

While children—even those under wartime conditions—are usually more resilient than adults, Grant says, Gaza wars are damaging them on a long-term basis: This is the third major violent conflict in Gaza in six years.

"This is the third time [children] have gone through such violence," he says. "How do you bounce back from that? How do children find their own path back from recovery?"

The parents of nearly all these children also grew up as refugees or as displaced people, so they will sustain the cost of what psychologists call "generational trauma"—meaning they will absorb their parents' and their grandparents' misery as well as their own.

Life inside the Gaza Strip is hellish even when there is no war. Aside from immobility—no way out and no way in—there is, on average, 12 hours of power cuts a day. In the first nine days of the present conflict there were 20 hours of blackouts.

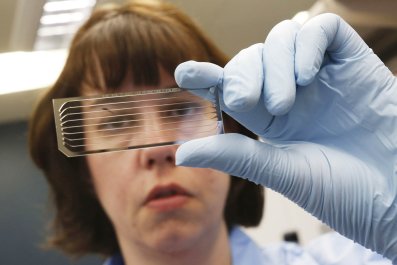

Even before the current fighting began, over 57 percent of the Gaza population was suffering from "food insecurity"—U.N.-speak for not having enough to eat. Gaza has 41 percent unemployment and 80 percent of the population are refugees. Nearly 95 percent of the water is not fit for human consumption. Sewage spills into the sea.

There is a certain smell in Gaza that is unbearable. There is a lack of public space, a lack of any kind of security and safety; and most of all the people suffer from an overwhelming feeling that the future will be no better.

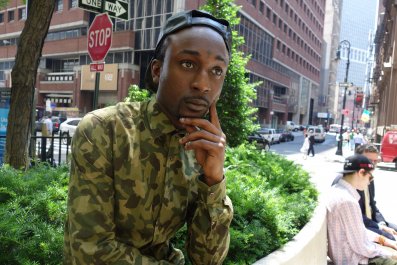

"I speak three languages and taught myself French as well, but what am I going to do with it? I can't get out of Gaza," says Mohammad, 24, who was working for Western journalists and asked that his surname not be reported for fear of recrimination. "Do you believe, I have never been beyond the Erez checkpoint? My contact with the outside world is reading the news on the Internet—when there is electricity."

Schools in Gaza are currently on summer holiday, but they are being used to house those fleeing the bombing. If the conflict does not end by September, there will be no space for teaching children.

Evidence that Gaza is in a state of total war was revealed by United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) that announced that rockets had been found in one of their U.N.-sponsored schools, "meaning that people are using U.N. spaces for weapons," said Sami Mshasha, an UNRWA official. "It's an utter disregard for the neutrality of schools."

Palestinians spend most of their days cowering at home from the falling shells or in shelters. The chronically ill—especially those with kidney dialysis—cannot make it to hospitals which are already overcrowded with the wounded. Children are kept indoors.

A UNICEF official, Catherine Weiber, says children are suffering from lack of sleep, are unable to eat and are "babbling to their parents—they are unable to interact. A lot of them won't let their parents out of their sight.

"They feel, If I let my parents go, they may never come back."

"We are hearing a lot of reports that even kids inside those shelters, who ran there to be safe, are having nightmares and unable to sleep," says Mshasha. "They are also listening to the sound of bombs constantly.…Now we will have another generation suffering."

One incident brought the plight of children caught in the crossfire to the fore: Seven children, all related to a fisherman from the Bakr family, went to the beach near the Al Deira hotel to play soccer. Four were killed by Israeli missiles. The first missile exploded, killing one of the boys. A second hit three other member of the group who were running away.

Those who were injured made it to a hotel where foreign journalists were watching in horror. Hamad Bakr, 13, was treated with shrapnel in his chest; his cousin Motasem, 11, was injured in his head and legs; and Mohammad Abu Watfah, 21, was hit by shrapnel in his stomach.

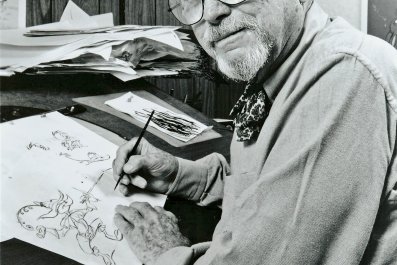

More than 20 years ago, at the end of the first Palestinian intifada or uprising (which lasted from 1987 to 1990), I worked on a project with the Israeli-British photographer Judah Passow and the Palestinian Gazan psychiatrist Eyad al-Surraj. Al-Surraj, a respected Gazan who ran the Gaza Mental Health Center, was a consultant to the Palestinian delegation at the Camp David 2000 Summit and a recipient of the Physicians for Human Rights Awards. (He passed away in 2013.)

We first tried to identify children who were suffering most from the Israeli occupation. When those children drew pictures at school, it was always of soldiers, guns, tanks and planes dropping bombs.

Passow and I went back 10 years later, during the second intifada, from 2000 to 2005, armed with the children's portraits in an attempt to find the same children and understand what had happened to them. Our results were depressing. Some of the children were dead, some imprisoned; a few lucky ones had gotten out of Gaza.

While, at the time of this writing, no Israeli children have been killed or injured in the current conflict, that does not mean that Israeli children are not suffering, too. Jonny Cline, an Israeli who runs the Israel side of UNICEF, says "You cannot compare suffering with suffering. If we did not have the Iron Dome defense, I am not sure how many Israeli children would be killed."

Cline says his own children have to run to a bomb shelter with only 90 seconds warning, and as a result they are not sleeping well, are not eating well and "are not themselves."

"As an Israeli my heart goes out to innocent Palestinian civilians," Cline says. "Because knowing what we suffer, I just cannot imagine what they suffer."