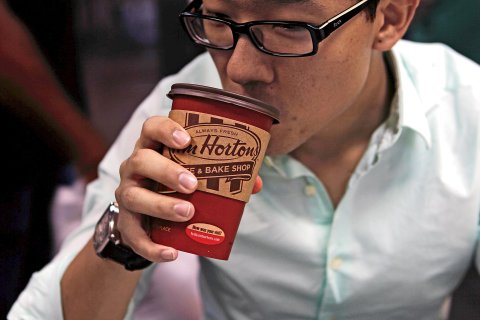

You and your wallet have a big stake in huge tax-dodging deals being crafted by big American companies, like Burger King merging with Tim Hortons, the Canadian coffee and doughnut chain.

Burger King is looking to swap the 35 percent corporate tax rate in the U.S. for Canada's 15 percent rate, even though its working headquarters will remain in Miami. The little people—the millions of us who pay our taxes week to week—will pick up some of the tax burden Burger King and other multinationals shirk through these so-called inversions, in which they move their headquarters, on paper, to escape taxes while continuing to enjoy all the benefits of doing business in America.

It's just one of several ways multinationals don't pay their fair share, and they get away with it because the federal government encourages such behavior. If Congress taxed you the way it taxes multinational corporations, you would have a much fatter wallet. If you were Apple, General Electric, Google or Microsoft, taxes would not be a burden at all. Instead, taxes would help you prosper.

How can a tax burden become a boon? Simple. Congress lets multinationals earn profits today but pay their taxes by-and-by. In effect, Uncle Sam is loaning these companies all that money they do not immediately turn over as taxes. And all of these loans come with the same attractive interest rate: zero.

Imagine how your bank statement would look if, instead of having taxes taken out of your weekly paycheck, Congress let you keep that dough in return for your promise to pay your taxes years or decades from now—and sometimes, never.

That's the extraordinary deal Congress gives many big American companies now sitting on hundreds of billions of dollars of what are, essentially, interest-free loans. Apple and GE owe at least $36 billion in taxes on profits being held tax-free offshore, Microsoft nearly $27 billion and Pfizer $24 billion, according to Citizens for Tax Justice, a nonprofit organization respected for the integrity of its numbers even by groups that dislike its progressive perspective.

The big companies get such "interest-free loans" in myriad ways, but most of them involve delaying the payment of taxes. Delay is a modern philosopher's stone, but instead of turning lead into gold, this tax alchemy makes the black ink of profits look red when examined by Internal Revenue Service auditors.

One technique is for American multinationals to pay their offshore subsidiaries royalties for the use of patents, logos and manufacturing techniques. This converts profits earned in the U.S. into tax-deductible expenses. You could do the same thing by moving a dollar from your left pocket to your right, but with one crucial difference—you won't get to deduct that dollar. But big companies do.

The use of offshore tax havens to convert profits into expenses stems from a 1986 change to Section 531 of the tax code. Starting in 1909, Congress imposed a 15 percent penalty on corporate cash-hoarding. That was supposed to encourage companies to reinvest and pay salaries and dividends, rather than weaken the economy by stuffing profits into the corporate equivalent of the proverbial mattress.

The 1986 amendment said companies could hold unlimited amounts of cash, provided it was in offshore accounts. Today at least 362 of the Fortune 500 companies have more than 7,800 tax haven subsidiaries, many stuffed with cash, according to a tiny nonprofit research organization, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Its detailed analysis of company disclosure statements found that in the five-year period from 2008 through 2012, no taxes were paid by 25 of 288 big American companies. Those 25 got cash back—refunds—from Uncle Sam on their tax bills. The immensely profitable Verizon earned more than $30 billion in profits over those five years, but instead of paying taxes, it collected income tax refunds of more than a half-billion dollars, which works out to a tax rate of minus 1.8 percent. Pepco, which counts on taxpayers to buy a big chunk of the electricity it sells in and around the nation's capital, dodged taxes so skillfully that it enjoyed a tax rate of minus 33 percent. Looked at another way, for each dollar of profit earned, Uncle Sam gave Pepco a grant of 33 cents.

How do these companies qualify for refunds? For starters, Congress lets companies reach back years to take advantage of deductions they could not take during unprofitable years, a benefit Congress has expanded in recent years. Most individuals are not allowed to do that.

Also driving down corporate taxes is a requirement that corporations keep two sets of books, one for shareholders and another for the IRS. Tax accounting lets companies depreciate, or write off, assets like computers, trucks and factories much faster than shareholder, or book, accounting. The difference creates a pool of interest-free profits that are supposed to be taxed in the future. This is why big utilities—Pacific Gas & Electric, Duke Energy, NiSource and Wisconsin Energy, among them—show negative income tax rates—they wrote off so much so fast that they could claim refunds for previous years' taxes.

You Versus Multinationals

Here's a quick overview of how very differently Congress taxes you and multinational companies.

For the vast majority of people with regular W-2 jobs, income taxes are taken out before you get your check. Congress does not trust you, so it demands its cut up front and requires your employer, bank and stockbroker to verify what they paid you.

But if you are a multinational, the government takes your word on how much you owe, subject only to the increasingly rare audits by the IRS. Top IRS auditors, paid about $150,000, each find on average $19 million of corporate taxes due each year, according to data the IRS discloses to Syracuse University researchers each month. Even though each auditor finds $126 in taxes owed for each dollar he or she earns in pay (a great return on investment), Congress has been steadily shrinking their ranks for more than two decades. It also hobbles auditors by allowing them to look only at issues the companies have been warned about, a practice similar to food, hospital and pet shop inspectors tipping businesses off that they are coming so they can clean up first.

For multinationals, the taxes on each year's profits do not come due immediately, but often years or decades later. If a company goes broke before the taxes come due, they might never be paid, as happened with Enron, which, subpoenaed documents show, regarded its tax department as a "profit center."

In effect, if you are a multinational corporation, the federal government turns your tax bill into an interest-free loan.

Not every company gets this deal. Mom-and-pop companies and purely domestic enterprises that do not require large capital investments for factories, trucks and other costly equipment generally have to pay their taxes annually.

Just imagine if each time you got a paycheck it came with a zero-interest loan from Uncle Sam.

Buffett's Whopper

For decades Warren Buffett has been borrowing interest-free money from Uncle Sam. Last year he had $57 billion of interest-free loans through his Berkshire Hathaway holding company. That was double the company's pretax profit of $28.8 billion in 2013, and about twice the total income taxes paid by the 68 million lowest-income taxpayers in the U.S.

Buffett's interest-free loans have been growing fast. Last year's loan balance was triple the $19.2 billion his company had borrowed interest-free in 2009. Buffett's cash stash is relevant because his company is financing the Burger King–Tim Hortons deal, putting up the money needed to buy out some Canadian shareholders. Buffett's partner in the deal is a Brazilian investment firm, 3G Capital, that already owns beer brands like Budweiser and Michelob, valued at $179 billion. Last year, Buffett and 3G bought H.J. Heinz, the ketchup and relish maker, for $28 billion.

In his "owner's manual" for Berkshire shareholders, Buffett boasts about using "low-cost, nonperilous" interest-free loans from the government that "allow us to safely own far more assets than our equity capital alone would permit." By using those interest-free loans from the federal government, 3G and Berkshire are rolling up a global fast-food and alcohol empire. Berkshire did not respond to a request for an interview.

Berkshire's return on equity—the ratio of profit relative to the value of the stake owned by investors—has run around 10 percent in recent years. That means investing the interest-free loans generously made available by Congress accounted for more than $5 billion of the company's profits last year.

One of Buffett's biggest operating companies, an electric utility called MidAmerican Energy Holdings, does not have to pay back its interest-free loans for 24 years. The length of such loans depends on a host of accounting and tax rules. A few years back, this same subsidiary revealed that it had one such loan for more than $600 million, only half of which would come due in 34 years.

To understand how valuable that advantage is, imagine you bought a house 34 years ago, in 1980, for $100,000. Ever since, you've been living in the house while making no mortgage payments because your loan is interest-free. Being smart about money, you decide every month to invest the amount you would have paid for your monthly mortgage payment—if you owed money to the bank. Back then, interest rates were so high your first month's payment would have been more than $1,000.

When 2014 arrives, you must pay half of the purchase price you agreed to in 1980. That's $50,000, but inflation has eroded the dollar, so the real cost to you is just $17,300. That's a very sweet deal, especially when you note that most home mortgages double in cost due to interest charges.

Coming up with the cash to make that $50,000 payment (that isn't even $50,000 anymore) is easy, even if your investments averaged just a modest 4 percent annual return. The magic of compound interest has swollen your account to $1.25 million thanks to those monthly investments. That's the equivalent of $432,000 back in 1980, when you bought the house, so you are way, way ahead on your $100,000 purchase, even after taking inflation into account.

No bank will give you this deal because it would almost instantly go bust, paying out many times in interest what it would collect to close out the loan. But Congress gives this deal to Buffett's company and many others all the time.

Here is where the deal turns very sour for small taxpayers. Even though companies delay paying their taxes, Congress spends as if all that money came in as quickly as the dough withheld from your paycheck. Then Congress lets companies use the tax money they did not pay to buy Treasury bonds, which pay interest. That's right—Congress pays companies to delay turning over their taxes, and it makes you pay the interest.

As our imaginary zero-interest 1980 mortgage deals illustrates, the interest compounds until it is worth far more than the tax, whose value is slowly but steadily eroded by inflation. In some scenarios, the government will pay $4 of interest for each dollar it ultimately collects in corporate taxes.

Now let's go back to those profits magically transformed into tax-deductible expenses and sent to overseas subsidiaries. The money is not really offshore, it is only in an account with a Cayman Islands or other tax haven address. The company can borrow the money back for short periods. A company with many offshore accounts can borrow from its Cayman Islands pocket today, its Irish pocket tomorrow and still delay paying its taxes.

Many companies, though, take a much simpler and safer approach when investing their untaxed profits. They buy U.S. Treasuries, those bonds the government sells because it spends more than it collects in taxes. In that way, the federal government pays companies to delay paying their taxes.

This is a classic heads-you-win-tails-I-lose economic plan: The government loans money to big companies interest-free, then borrows it back with interest.

Many of the big companies with untaxed profits offshore say they will bring the money back and create jobs if Congress declares a tax holiday or gives them an 85 percent discount on their deferred tax bills. Congress did just that in 2004 after advocates said it would create 660,000 new jobs. Didn't happen. Pfizer brought home the most, $37 billion, escaping $11 billion in taxes. Then Pfizer fired 41,000 workers.

There's another aspect to this gambit: High corporate tax rates benefit multinational corporations by increasing their profits. That is an astounding fact, so let's walk it down: The higher the tax-rate, the bigger your "interest-free loan." On $1 billion of profit at the current 35 percent tax rate, the interest-free loan is $350 million, but if Congress were to cut the tax rate to 25 percent, the size of your loan would shrink by $100 million.

The Doughnut Dodge

There's another key ploy that helps multinationals profit off their taxes. Edward Kleinbard, for decades one of the savviest Wall Street tax lawyers, says companies seek to earn profits in high-tax jurisdictions and then use accounting tricks and tax rules to siphon money to low- or no-tax jurisdictions.

Kleinbard, now a professor at the University of Southern California's Gould Law School, explains that a basic tenet of economics can be altered by tax rules in a way that encourages companies to operate in the highest-tax-rate country they can find. In a mature industry, like hamburgers or coffee and doughnuts, companies tend to earn the same after-tax profit margin. Any company that can earn even a tiny bit more than average profits will tend over time to vanquish the competition.

Imagine that the average fast-food industry after-tax profit is 5 percent. In one country, profits are taxed at 35 percent, in another 15 percent. To hit that average, a company in the high-tax country needs to earn nearly 8 percent pretax, while the low-tax country only needs to earn about 6 percent.

But what if tax rules let the company in the high-tax country siphon profits to the lower-tax country, where the 15 percent tax is imposed, or to a tax haven, where no tax is imposed.

Since the high-tax country operator pays no corporate income tax in this case, it earns not the worldwide average of 5 percent after profits, but nearly 8 percent. That much bigger profit margin means it can build financial muscle and use it to smack competitors.

This appears to be what Buffett is up to in the Burger King–Tim Hortons deal. That merger is part of a global consolidation of three mature industries—beverages, fast food and condiments. 3G Capital owns the world's largest beer company, ABInBev, whose brands include Budweiser and Michelob, and the largest nonfood retailer in Latin America, Lojas Americanas. In 2010, it expanded by purchasing Burger King for $4 billion. It says the chain is now worth $10 billion and will become much more valuable after the merger, thanks to better management and lower tax bills.

Last year's 3G deal for H.J. Heinz was financed by Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway holding company, which bulges with cash, thanks to that $57 billion borrowed interest-free from Uncle Sam.

Buffett, who has criticized the U.S. tax system's inequities, has figured out a new way to game the tax code. In this case, profits earned in America will be taxed in Canada, instantly raising Burger King's after-tax rate of return. All else being equal, the tax rules will give Burger King an advantage over McDonald's, Wendy's and all the other joints that now prefer the label "quick service" to "fast food."

Kleinbard says the ultimate goal of such international tax games is "stateless income," a fancy way of saying "earn profits without paying taxes." Because taxes are imposed by states—by governments—anyone who can earn profits in a high-tax country and then move them to a haven where no tax is owed should ravage the competition.

The Burger King–Tim Hortons merger is just one of many in which top tax lawyers working for multinational companies have figured out how to get closer to that corporate paradise of "stateless income." Fear that day—as multinationals duck their U.S. taxes, you get stuck with the bill.

Burger King made its mark in America with a slogan: Have it your way. When it comes to taxes, it looks like taxpayers may have a new slogan: Pay Burger King's way.