"Your casino loses money," Michael Corleone tells Moe Greene in The Godfather. "Maybe we can do better." Don Corleone's son should have met the organised crime groups currently operating in Europe. According to a pioneering EU-wide study, to be presented to the European Commission later this month, the Italian mafia and its Russian, Chinese, Georgian and motorcycle-borne rivals generate annual revenues of over €19bn on counterfeiting alone, and park their profits in legal enterprises.

"The way that organised crime groups make money is changing," explains Ernesto Savona, the director of the Transcrime research centre at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan and coordinator of the team behind the report. "Just like legal enterprises, organised criminal groups today can be large, mid-sized or small. A smaller group will, for example, make money on smuggling cigarettes, whereas a larger group has much more extensive activities. They mirror the real world."

The infiltration documented by Savona's team – which includes specialists from Italy's financial police, the Guardia di Finanze; France's AGRASC agency that handles confiscated assets; Ireland's Criminal Assets Bureau; Finland's Police University College; and universities in Italy, Spain, Britain and the Netherlands – is certain to cause eurocrats many sleepless nights. Organised crime groups, the report shows, don't just operate in Europe and launder their money here: they also invest it in business ranging from British clothing shops to Finnish nightclubs.

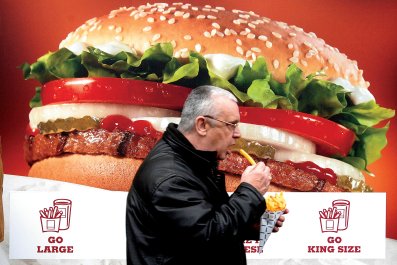

There are enormous amounts of money that need to be laundered and invested. According to the researchers' estimates, based on analyses of confiscated criminal assets, last year organised criminal groups earned €19bn on counterfeit goods, €6bn on heroin, €5bn on cocaine and cannabis, respectively, and €4bn on sexual exploitation, with a profit margin of over 30%. Once, Mafiosi – whether of the Italian, Russian, Chinese, Georgian or motorcycle variety – invest in legal companies, they generate lower gains. Still, they outperform Moe Greene. "They invest in legal businesses as a way of laundering money and of becoming clean entrepreneurs, but making a profit is a motive as well", notes Savona.

Britain now plays unwitting host to investment by Russian, Georgian and Chinese gangs in banking, restaurants, real estate, retail and sports and betting. The mafia, however, remains the criminal investment lord of the British Isles, with the Calabrian 'Ndrangheta syndicate investing in real estate, the Apulia-based mafia opting for casinos, sports and betting, and the Campania-based Camorra, in true Warren Buffett-style, parking its proceeds across a range of sectors, including grocery stores and construction.

In Finland, meanwhile, Russian motorcycle gangs invest in auto repair shops, cleaning companies, private security services and sex establishments. Chinese gangs opt for real estate and wholesale and retail trade in France; in the same country, Russian and Georgian groups prefer hotels and real estate. In Germany, the Camorra specialise in clothing shops, while Cosa Nostra prefers the construction business and 'Ndrangheta runs factories, restaurants (some 100 of them, according to Italian prosecutors), hotels and grocery stores. In its most recent report on organised crime, from 2012, Germany's BKA federal criminal police reports criminal proceeds of €580 million, a 70% increase over 2011. Due to the risk of defamation lawsuits, Savona's team can't publicly name companies suspected of having Mafiosi investors.

Russian, Georgian and Chinese gangs are brazen enough to invest in Italy, where the mafia has long parked its proceeds in commercial activities that now range from sports to agriculture and mining. (According to a previous Transcrime study, mafia revenues account for 1.7% of Italy's GDP.) The Chinese competitors opt for investments in clothing shops, money service businesses, retail, real estate and restaurants, while Russian gangs focus on agriculture and transport in addition to retail, a perennial criminal favourite. Indeed, because they don't possess a great deal of specialised business expertise, criminal gangs particularly like businesses such as shops and restaurants. "You don't need a lot of skills to open a pizzeria," notes Savona. Both 'Ndrangheta and Costa Nostra have, however, started investing in renewable energy, and in Finland Hells Angels & Co invest in IT services.

Indeed, squeaky-clean northern European countries (Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway join New Zealand as the world's five least corrupt countries in Transparency International's most recent ranking) now attract considerable gang investments. "Italian gangs don't invest much in Italy anymore due to the risk of detection," notes Savona. "Plus, the value of real estate is rising faster in, say, London and Stockholm than in Palermo [the home of Cosa Nostra]. As a result, they invest in countries like Sweden. They don't speak Swedish, but they don't have to. All they need is an accountant who'll help them invest their money. They don't kill anybody and lie low in general, so the police don't bother them."

In the Netherlands, criminal gang members speak neither Dutch nor English, observes Stan de Jong, co-author of the book De Italiaanse maffia in Nederland, "so they're very easy to spot, but, until recently, the police weren't paying attention." Thanks to its liberal drug legislation and excellent infrastructure, as well as harbours and Amsterdam's busy Schiphol airport, the Netherlands is an attractive destination for organised crime, says de Jong. Today Russian and Georgian crime syndicates give the mafia a run for their investment in the Netherlands, parking money in hotels, restaurants and real estate. Motorcycle gangs, for their part, opt for private security firms, hotels and restaurants.

No western European country escapes the investment largesse of organised criminal groups, which harms not just law-abiding entrepreneurs competing with Mafiosi-funded establishments, but private citizens as well. "Organised crime groups inflate every market they get into," says Kenneth Rijock, a Miami lawyer-turned-money launderer for drug traffickers. "For example, they buy apartments at above-market rates, pricing others out of the market." After serving a prison sentence for money laundering, Rijock built a new career as a financial crime consultant. (Europol declined an interview request.)

Much like any other private investor, crime syndicates either start and operate their own clean enterprises or invest on ones run by ordinary entrepreneurs. And the restaurateur or construction-firm-owner who accepts 'Ndrangheta or a Russian gang as an investor? He may be desperate or simply naive.

"Especially in financially difficult times one has to be careful," says Timo Vuori, an executive vice president at the Finland Chamber of Commerce. "You may have done business with a company for many years, and all of a sudden that business partner gets additional cash. That's something to pay attention to."

Savona, who is considered Europe's leading authority on organised crime, says: "A lot of businesses have had a hard time during the economic downturn. Then these people come and make a great offer. The entrepreneur may be a law-abiding citizen, but by accepting the investment he becomes a partial criminal."

The fundamental problem is this: the legal economy benefits from infusions of money, while criminal gangs need a place parks theirs. "Now law enforcement agencies are trying to stop the money from being laundered, which is exactly the right approach, but it's not enough," says Savona. He suggests creating Mafiosi heat maps that would allow police forces to focus their efforts. Amsterdam may find itself hotter than Palermo.