People who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can be tormented by memories of something terrible that resurface again and again. There is no widely agreed upon way to easily and quickly treat the syndrome, and some evidence suggests that the drugs currently approved to treat it—Zoloft and Paxil, for example—treat PTSD's symptoms rather than its root cause.

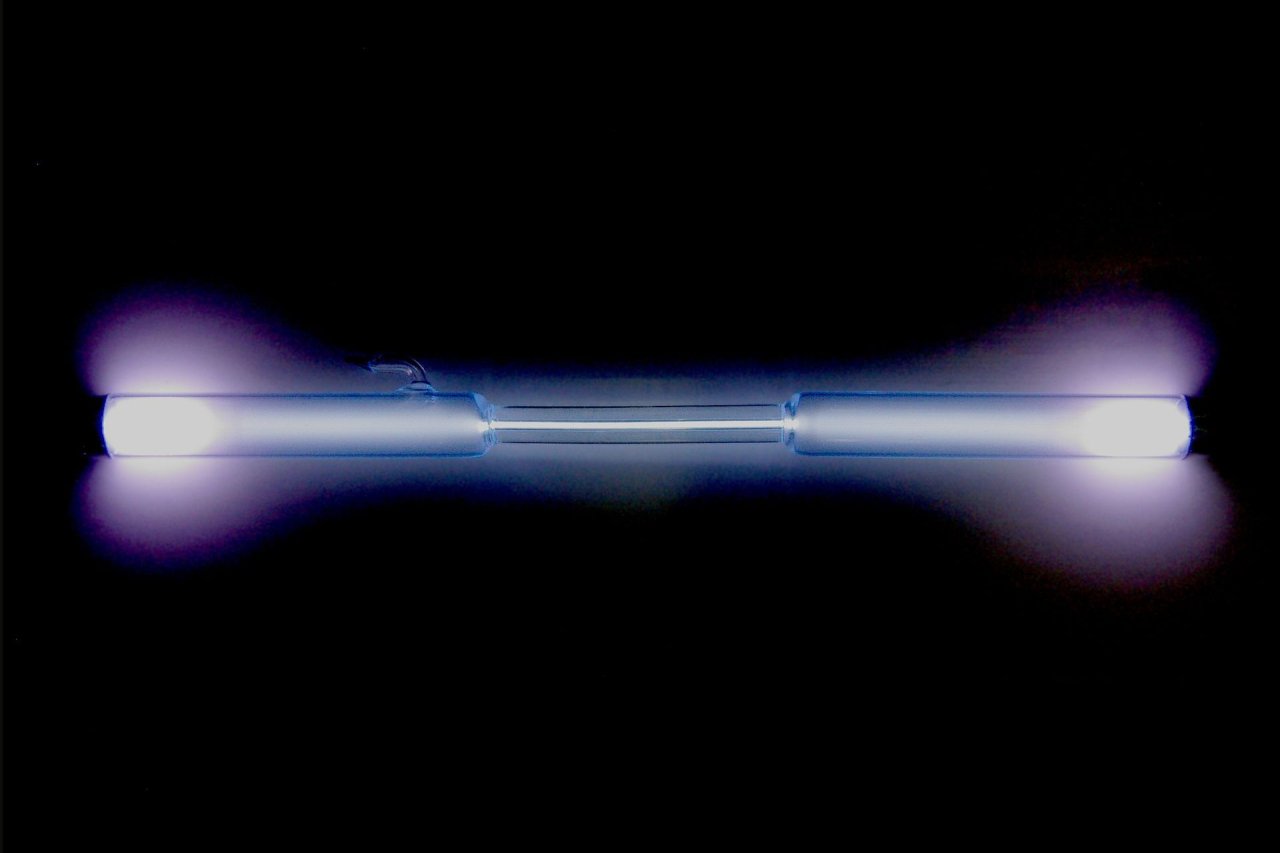

A new study published in PLOS ONE demonstrates that xenon, a noble gas already used in humans as an anesthetic, can disrupt the process in which the traumatic memories are re-encoded, and/or the fear that goes along with them, says Edward Meloni, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard University at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, and one of the study's co-authors. The results suggest it could be used as a tool to help people suffering from PTSD, he tells Newsweek.

When you recall an event, you often experience some of the same emotions you felt at the time, such as fear. For a brief while after the experience, the memory can also be changed or added to, in a process called reconsolidation. The theory is that xenon prevents a memory from being re-encoded, which may allow it—or its emotional significance—to begin to fade.

In the recent study, co-authored by Meloni, researchers played a musical tone before giving rats a small electric shock; the animals learned to become fearful when they heard the sound. But when those rats inhaled air made up of 25 percent xenon for an hour after hearing the sound, they became less fearful of the noise when it was played again, compared to rats not exposed to the gas. The authors say the study shows that xenon gas interferes with the re-encoding of the "fear memory or the emotional component of it."

"We really think we blocked this process of reconsolidation," Meloni says. To treat PTSD, xenon gas would be given to a soldier, say, after they recalled a traumatic memory in a psychiatrist's office, to hinder reconsolidation, and thereby help dampen that memory or its associated pain.

The researchers found that in mice, the gas works by interfering with a receptor in the brain, called an NMDA receptor, thought to be involved in the reconsolidation process. There's reason to believe xenon would work similarly in humans, said Wendy Suzuki, a neuroscientist at New York University who wasn't involved in the work. The researchers plan to test xenon's effect on memory reconsolidation in people within a year, although not yet on patients with PTSD.

"The exciting thing about this research is that it's using a substance that's already used [safely] in humans," Suzuki tells Newsweek.