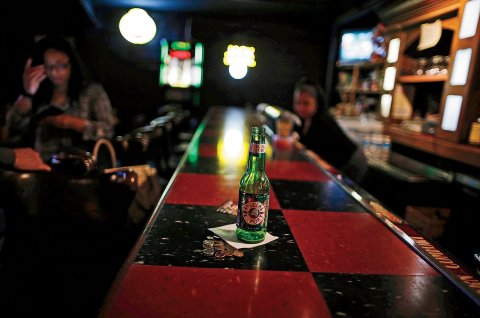

I don't really like dive bars, but I am always sad when one closes. I prefer to drink in a clean, well-lighted place where I don't have to watch Yankees highlights or listen to the discomfiting political ideas of ancient barflies. But many others like the dimness, and the sweating bottles of Budweiser, and talking sports with someone they don't know and never will, except for the duration of one boozy evening.

These pleasures, to be found in dive bars, used to be readily available on the street corners of New York and Chicago, in establishments that had an Irish name, or a Polish name, or maybe no name at all—just a neon sign announcing the presence of cheap booze in uncomplicated arrangements. No longer so. To watch the agonizing death of the dive bar is to know that a species integral to urban ecology is disappearing. Regardless of your affection or animosity for that species, its extinction says nothing good about the way we live.

You may, at this, point, ask an entirely reasonable question: What, exactly, is a dive bar, anyway? To which I will, in turn, supply an entirely honest answer: I have absolutely no idea. Unlike flora and fauna, watering holes do not abide by Linnaean taxonomy. Nevertheless, several negatives readily apply: This is not the place for the $18 kiwi-tini, nor for an Upper Peninsula artisanal ale lauded by the high culinary priests of Bon Appetit. The dive is not new, the dive is not fashionable, and the dive is not in the newspapers unless 1) it is closing, as dives often are, and 2) it is the setting of a crime, as dives also often are. The dive is not beautiful, and neither are the people within it. And that's how they like it, thank you very much.

"Cigarette burns on the Formica table tops, duct-tape suturing the vinyl booths and bar stools, and the wood of the bar is worn smooth by all the elbows leaning heavily on it over the years"—that's how Jeremiah Moss, the editor of the history blog Jeremiah's Vanishing New York, describes a dive. Seems right to just about anyone who's bellied up to the bygone Bar Timboo of Brooklyn or Divebar in Las Vegas, also no longer of this world. With a few variations, the above could also describe the Two Way Inn of Detroit, the Wharf Rat in Baltimore and the Lamplighter in San Diego. Every major American city has at least one web page devoted to its best dives. The best cities have several such pages and, accordingly, several such bars. (The Europeans, so tortured by time, have historic taverns, but not true dive bars, outside of the United Kingdom, though if there is a magnificently filthy watering hole in Bucharest I should know about, please do tell.)

But there are fewer and fewer of these places where a "beer back" won't do serious damage to a $20 bill and where you just might talk to a person who is not exactly of the same demographic as you are, who does not have a Twitter handle, who does not—funny thing!—have a good friend who went with you to Cornell. Where you will not have to hear a 10-minute lecture on the provenance of the nebbiolo, nor face pressing questions about what you'd like on your cheese plate.

All across the land, laments have been going up for dive bars in recent years, as beloved establishments pull their last pint, replaced by corporate outposts that are far more morbid than what they've replaced. This isn't a trend; it's an epidemic. Three dives closed in San Francisco last year (the Nite Cap, Pop's Bar and the Attic) in the hobo redoubt that was the Tenderloin and the once-working-class Mission District, leading one blogger to write that the "day when a serious barfly won't have a stool to sit on is (scarily) approaching."

And this spring, on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C., Remington's served its last drink. The place was lovingly described by the Washington City Paper as "an utterly non-updated country western gay spot with some of the worst carpet in the Southeast quadrant." It was, as many dives are, inconsequential yet necessary, a bulwark against the glacial sweep of gentrification. Or, as the City Paper acidly put it, "If you want to cram into a glossy box of cool people and sip a cocktail for the price of a dinner entree, there are plenty of places [in Washington, D.C.].… If you want to wear whatever the hell you want and chat with decent, friendly strangers over cheap beers, your options in my neighborhood are rapidly depleting."

New York's dives are no safer, with several of the city's best closing in the past couple of years: Milady's in SoHo, a final trace of true Manhattan in a neighborhood of dismaying inauthenticity; Jackie's 5th Amendment in Brooklyn's Park Slope, where you might have seen a wizened matron soothing her sorrows in the early morning, next to a bus driver just off his shift. "New York's dive bars are living up to their name lately," The New York Times quipped. "Because several of them are going down."

And in Chicago—another town with a blue-collar population renowned for a love of no-nonsense drinking—Marie's Rip Tide Lounge, a 60-year fixture in the Bucktown neighborhood, closed last summer despite great efforts to keep it alive. "This place has the heart and soul of this neighborhood, and it's the last place like it," said one patron at the dive, which had hosted celebrities like Vince Vaughn, Bill Murray and John Belushi.

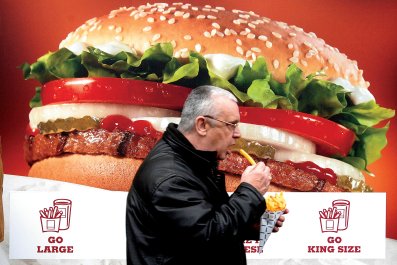

The reasons for the disappearance of dive bars can be found in Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century. No, seriously. The way we drink, where we drink, largely reflects how educated we are, how much money we have, whether we even have the leisure time for unhurried bibulous consumption. The death of the dive suggests that we don't drink together anymore, as a single nation yearning for a quick post-work respite or Saturday-afternoon escape. The rich can pay several hundred dollars for a single coveted shot of Pappy Van Winkle's Family Reserve; the poor, meanwhile, drink Cobra out of paper bags and Miller Lite in busted lawn chairs. The dive bar used to be for those in the middle, those who had a little money and a little time, not to mention a little curiosity about the human race: the mid-level bank manager, the cop, the teacher, the hopeful writer, the waitress. They dove together into the sloppy democracy of cheap beer.

I am not saying that Cheers is the closest we'll come to Plato's Republic…well, maybe I am saying that. When I think of the dive's demise, I am reminded of what The New Yorker's Joseph Mitchell wrote of McSorley's Old Ale House, which has many of the trappings of the dive but is too old and famous (Abraham Lincoln visted, according to local lore) to have become one. He wrote about the place in 1940, long before it became a Lonely Planet staple, not to mention a holding pen for Midwestern fratboys:

It is possible to relax in McSorley's. For one thing, it is dark and gloomy, and repose comes easy in a gloomy place. Also, there is a thick, musty smell that acts as a balm to jerky nerves; it is really a rich compound of the smells of pine sawdust, tap drippings, pipe tobacco, coal smoke, and onions. A Bellevue interne once said that for many mental disturbances the smell in McSorley's is more beneficial than psychoanalysis. It is an utterly democratic place. A mechanic in greasy overalls gets as much attention as an executive from Wanamaker's. The only customer the bartenders brag about is Police Inspector Matthew J. McGrath, who was a shot-and hammer-thrower in four Olympics and is called Mighty Matt.

If that sort of thing strikes you as overly romantic, then consider the practical implications of the dive's demise: These bars are canaries in the real estate gold mine. Once they go, more upscale establishments will inevitably follow. Earlier this summer, for example, Kenn's Broome Street Bar—once an artists' hangout, later a New York tourist destination—announced it would vacate the SoHo corner it had occupied for four decades. The place wasn't a dive, but it wasn't serving duck sashimi, either. Its new owner promises a "fabulous" restaurant. Perhaps he will manage to attract the Kardashians, as he surely hopes.

Right around the same time that the death of Kenn's was grimly announced, famed restaurateur Danny Meyer revealed that his flagship Union Square Cafe will have to leave its long-standing location because the neighborhood got too nice: The bums left, the rents climbed, the bankers came, the rents climbed even higher.

"It is sad that the more 'successful' a neighborhood becomes, the more it gradually takes on a recognizable, common look, as the same banks, drugstore chains and national brands move in," Meyer wrote in a Times op-ed. "Be honest: Would you rather have one more bank branch in your neighborhood, or another independent restaurant?"

Moss, the Vanishing New York editor, thinks that, soon enough, the dive bar will be gone entirely from American cities that have welcomed—and benefited from—gentrification. "The new New York is sanitized and safe," he told me. "Curated and fussed over, with an emphasis on financial status. It's the opposite of everything divey. The new New Yorkers skeeve everything that reminds them of aging and death. They want a constantly re-lifted face-lift."

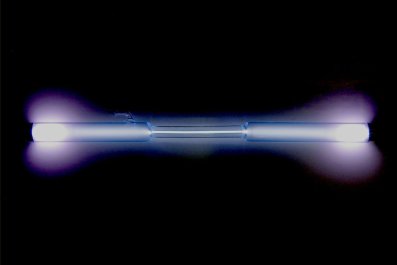

On a recent afternoon, I went to the Subway Inn, a dive bar on Manhattan's East Side that has been fighting to stay open. Geographically, it is not far from "one of the dives / On Fifty-second Street" where W.H. Auden sat, "Uncertain and afraid / As the clever hopes expire / Of a low dishonest decade." That dive—Dizzy's Club—is the setting of Auden's most famous poem, "September 1, 1939." The dim bar was, for him, a shadowy place to contemplate shadowy truths, a church pew that also happened to serve drinks.

The Subway Inn, preparing for the big sleep on the Thursday of my visit, does not appear to be full of either poets or penitents. The day is strangely clement, as if the weather gods have forgotten it is August. The bar, though, is full: a couple arguing loudly in Spanish; men sitting alone, gazing up at the truTV show playing on the screens above; a woman who looks languid and intriguing, full of some complex longing that makes her linger over a honey-colored beer.

The bar is as true a dive as could be, from the neon sign outside to the Christmas lights that outline the bar, the Budweiser adverts, the football helmets, the bottom-shelf booze. But there are touches of grace, too, including a picture of Marilyn Monroe, who supposedly used to visit with her then-husband Joe DiMaggio. No stars here today, though, just ordinary people who want a drink. Or maybe need one.

"What a bummer," I say to the bartender about the upcoming closure of the bar.

"Yeah, it sucks," he answers, for anything more eloquent would not be right for a place like this. It was "just a matter of time," he says, as of an old man simply awaiting death, no longer struggling against fate. Above us, from the faux-leather tiles of the ceiling, flutter Guinness pennants. They have been there since St. Patrick's Day.