Meat is a nasty business, filled with blood, guts and, yes, shit. While there's nothing in the U.S. today that matches the hellish conditions described in Upton Sinclair's The Jungle at the turn of the last century, there is no avoiding the fact that if we want to eat meat, we need to do things that are stomach-churning for the average person: kill things, cut them up, pack the pieces into containers and ship them out.

We've all done an excellent job of hiding this process from our daily lives. In the time we've moved out of the country and into cities and suburbs (in 1910, 72 percent of Americans lived in rural areas; in 2010, only 16 percent did), we've both literally and emotionally distanced ourselves from the provenance of our dinners. In her book on the history of meat production in the U.S., In Meat We Trust, Maureen Ogle notes that as early as 1870s, city dwellers were desperate to get the dirty business of the slaughterhouse off their cobblestone streets. And as cities became less industrialized and more "refined," the sight and smell of slaughter became even less tolerable.

So we drove meat production into the hinterlands, in the process encouraging the growth of massive meat conglomerates that did much more than simply process: They grew, slaughtered, processed, shipped and marketed. To keep up with demand, they used all the resources they could marshall to become ever more efficient at these tasks. In 2010, we consumed 34,156,000 metric tons of the stuff total. Per person, we average 270.7 pounds of meat per year, well above the world average of 102.5 pounds and second only to tiny Luxembourg.

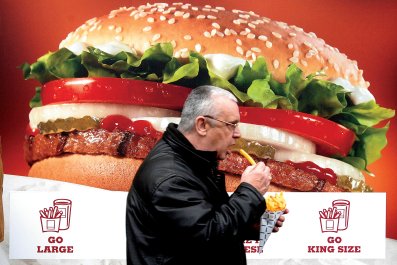

All the while, we demand that meat stay good and cheap. "Meat is the culinary equivalent of gasoline," writes Ogle, referring to the market's inability to bend at all with regard to cost. "When meat's price rises above a [vaguely defined] acceptable level, tempers flare and consumers blame rich farmers, richer corporations or government subsidy programs."

This has led to the rise of factory farms, which are farms in name only—they have more in common with an electronics manufacturer than what the average American thinks of when he or she hears that particular F-word. "A lot of people like bacon and hamburgers and turkey," says Michael Martin, director of communication at Cargill, the country's second-largest meat producer. "But the reality is that in order to get that product, we have to harvest animals and disassemble them. And people don't necessarily want to know all the details about how that's done."

Pink slime is one of those inconvenient little details. The much-maligned meat product was a masterful feat of food engineering—a means by which beef trimmings formerly tossed in the trash could be turned into hamburger patties. Because of its ability to deliver affordable ground beef efficiently to the masses, "lean finely textured beef," or LFTB (the industry term for the stuff), became a ubiquitous part of the industry landscape. And because the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) said there was no need to put LFTB on the label, the public never knew it existed—until we found out. Then, the outrage.

The story was all over the Internet—always with the inflammatory term pink slime, and often accompanied by a provocative image of what looks something like strawberry soft-serve being poured into a cardboard box. Media (traditional and social) reproduced the photo repeatedly, crying out that this was no way for meat to look; even more damning, many argued that LFTB wasn't beef at all but filler, maybe fit for dogs, but not much else. It later came out that the popular image was not of LFTB at all but a chicken-based product of unknown provenance. But the damage was done—the image is still being used incorrectly to illustrate pink slime today.

The hysteria spurred the kind of consumer outrage and grassroots "vote with your dollar" momentum of which Ralph Nader can only dream. But the reality is that pink slime is no more of a public health threat than most other pieces of animal flesh you can buy at your local A&P. That doesn't mean there was no good done here: The pink slime story exposed a deep rift between the U.S. meat industry and the public, characterized by mistrust and deceit. The public realized it had been treated like children, told to trust that what was given to it was for the best. And in many ways we were innocent as toddlers: We didn't have the tools to ask the questions that needed asking. Now we do, and the questions, of which there are legion, may be best summed up in one: What else might they be hiding?

Beef Products, Inc.'s downfall began just days before New Year's 2010, when The New York Times published a report by Michael Moss on hamburger and food safety (which would eventually earn him a Pulitzer Prize) in which the term pink slime was first put into print. Moss's article told America that LFTB was omnipresent: in the burgers served at fast-food chains like McDonald's and Burger King, in public school lunches and in the meat aisle of grocery chains like Kroger's, Safeway and Sam's Club. By some estimates, BPI's LFTB could be found in some 70 percent of our nation's hamburger meat.

The company reached these heights by cornering a market it essentially created. BPI's founder and CEO, Eldon Roth, now 72, built his fortune by solving a decades-old problem: After you break down a cow into the cuts of meat we all know and love (filet mignon, short ribs, sirloin), you're left with mostly bone and fat, with pieces of muscle protein still attached here and there. For years, it was too expensive to have someone hand-cut those bits of meat out of the fat, so they'd pretty much go to waste, tossed into the rendering barrel to become some "value-added" product (in industry parlance) like pet food.

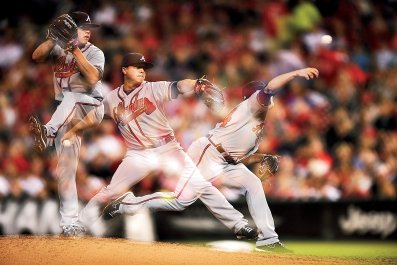

In the early 1990s, BPI developed a way to separate that lean protein from the fat. Here's the simple version: You trim off all the fat from the bone, grind it up, put it in a big steel pot, warm it up to 100 degrees Fahrenheit, then spin it in a centrifuge. The fat stays up top; the heavier protein sinks to the bottom.

In 1993, BPI submitted its process to the USDA for safety approval, and it was rubber-stamped. Over the next decade, the company saw an explosion in growth, because it turned out LFTB was a godsend. It was the right place, right time: in the middle of what might be called the "fat revolution"—a shift in dietary habits launched in 1977 with Senator George McGovern's landmark "Dietary Goals for the United States," that urged Americans to eschew all forms of cholesterol and fat. Fatty cuts of meat were to be avoided—pork became "the other white meat" in an effort to adjust to this new world order—and leaner burgers were a good way for a red-blooded American man to align his appetites with his health concerns.

LFTB, high in protein, could be added to fatty ground beef to bring down the protein-fat ratio. And in the 1990s, a tool to get, say, an 80-20 shipment of ground beef to 90-10 was a huge competitive advantage. Others—primarily Cargill (which calls its version "finely textured beef")—would get in the game, but BPI had a massive lead.

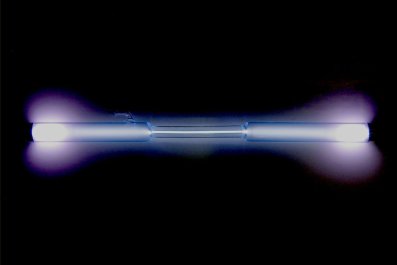

After the Jack in the Box E. coli 0157:H7 outbreak in 1993 (which had nothing to do with BPI), the company went to work on a system to ensure its meat was untainted. Eventually, it added a processing step that treats the LFTB with an ammonium hydroxide gas and then flash-freezes it. Ammonium hydroxide gas had already been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and was classified as a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) substance, and studies commissioned by BPI found that, by temporarily raising the pH of the meat to higher-than-normal levels, it could kill pathogens, including disease-causing bacteria like E. coli. The company submitted its process to the USDA and was granted approval in 2001.

BPI's decision to test for bacteria was, again, ahead of trend; the USDA didn't begin testing hamburger meat sold to the general public for pathogens until 2007.

In his 2009 report, Moss claimed he had some new facts that showed LFTB wasn't as safe a product as the industry—and industry regulators—had made it out to be. Between 2005 and 2009, he reported, school lunch program testing had found E. coli three times and Salmonella 48 times in BPI's meat (testing also showed that ground beef containing LFTB was four times more likely to contain Salmonella). He also cited a 2002 internal email sent by Gerald Zirnstein, a USDA microbiologist and investigator at the time, in which Zirnstein called LFTB "pink slime."

The dominoes began to fall.

On April 12, 2011, ABC aired an episode of Jamie Oliver's Food Revolution on which Oliver walked a studio audience (many of whom looked on the verge of emptying their stomachs) through a rudimentary version of BPI's process. It was more theater than science: Oliver took a bunch of primal beef cuts, put them in a laundry drying machine, dumped liquid ammonia on them, and then put them through a meat grinder and called the result "pink slime."

In early 2012, McDonald's and other consumer brands announced they would no longer use LFTB in their hamburgers. On March 6, 2012, Bettina Siegel, a former lawyer and founder of The Lunch Tray, a blog focused on childhood nutrition, started a Change.org petition calling for the USDA to stop the use of LFTB in ground beef destined for school food. "Consumers vote with their dollars and corporations listen," Siegel tells Newsweek, "but almost 20 million kids eat school lunch every day solely because they're economically dependent upon school meals. Those kids have no voice and no choice about what they're served."

Her petition title? "Tell USDA to STOP Using Pink Slime in School Food!"

A day later, ABC's World News With Diane Sawyer began a multipart investigation into LFTB, with Sawyer and investigative reporter Jim Avila continually calling the product "pink slime" and "filler." Zirnstein, the former USDA investigator cited in the Times story, came on ABC to call the stuff "an economic fraud" and a "cheap substitute" on-air. As the ABC series progressed, the USDA was bombarded by media and public requests for information on pink slime. At first, no one seemed to know how to respond—employee emails (acquired under a Freedom of Information Act Request) show internal division about the safety of LFTB. Some expressed surprise and disgust:

"The thing that gets me is why do we learn about products like this through the news media and not from the agency?" wrote one meat inspector (whose name was redacted—as were most).

"I don't agree with allowing LFTB (lean finely textured beef), a.k.a. pink slime, to be called beef," wrote another inspector. "It's a cost cutter, plain and simple.… it should be on the label as it is and not called beef."

But others were much more positive. "I always found it to be a strange process, but I'd still eat the beef," wrote one inspector. "Pink slime is not an adulterant," said another employee of the USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). "It is a meat product, and all packaged meat pretty much has it and has had it for years. The only issue now is that someone saw it and reacted unfavorably. The slime is actually meat that is processed more than ordinary meat like ground beef."

As the days passed, their tone moves from confusion and concern to frustration to cynical humor. In one email chain about an upcoming company retreat, one FSIS employee asked another "Can you bring some pink slime with you?" In another email chain a couple of district supervisors had an emoticon-laden exchange in which they joked, "Personally I've always been partial to green slime myself!" and "I understand that can also be used for fuel?"

While the regulator debated internally, consumer-facing beef purveyors had no choice but to respond, and fast. Burger King, Kroger, Safeway and Wal-Mart were among many others that made announcements in mid-March that they would no longer carry any products containing LFTB. By March 15, Seigel's petition had 200,000 signatures, and the USDA announced that starting in the fall of 2012, school districts would be given the choice of purchasing beef with LFTB or beef without (which cost 3 cents more per pound).

In the meanwhile, sales dropped precipitously. BPI had to first suspend operations and then eventually close three processing plants, in Waterloo, Iowa; Amarillo, Texas; and Garden City, Kansas.

Today, BPI is embroiled in a lawsuit filed against ABC and its reporters, claiming defamation and product and food disparagement. BPI claims to be losing more than $20 million in revenue every month because of the bad press. Its CEO, Roth, has disappeared from the public eye and has been described by associates as "heartbroken."

LFTB was and is, by scientific standards, 100 percent pure beef.

"From a scientist's perspective, beef is beef is beef," says Robert Gravani, a professor of food science at Cornell University. "[LFTB] is not a filler, and it's not anything else."

It's also safe. When contacted by Newsweek, BPI would not comment on allegations by The New York Times and ABC, citing its ongoing litigation with ABC. However, despite the concerns raised by Moss, Newsweek was unable to find a single confirmed incidence of food-borne illness linked to LFTB. There was a recent Minnesota case where a 62-year-old man with Down syndrome, Robert Danell, died from complications related to E. coli. The attorney representing Danell's family, Bill Marler, filed a complaint claiming that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), FSIS and local health inspector evidence clearly connects the tainted beef to BPI, Tyson Fresh Meats and JBS Swift. But the results of that case have been sealed by the Stearns County Court, so it's unclear what may have come out during the trial.

Testing done in the past few years by the USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service (which, despite its name, is the division responsible for monitoring the "product quality" of the public school lunch program) show that the E. coli and Salmonella numbers Moss originally cited are not particularly extraordinary. In just 2012, for example, one ground beef provider had 44 incidences of Salmonella (compared with 48 over a four-year period for BPI). In 2013, another vendor's meat tested positive for E. coli five times (compared with three over four years for BPI).

Of course, in both cases, the data are cherry-picked. The reality, as Ferg Clydesdale, a food scientist at the University of Massachusetts's Department of Food Science Center for Foods for Health and Wellness, points out, is that all uncooked ground beef carries with it some risk—that the health risks are "inherent to the product." When you chop up meat you are creating tons of surface area that can be exposed to pathogens. "Whether you make it from a 'good' cut of beef or a less 'good' cut of beef is irrelevant," Clydesdale says.

"There is no way to guarantee absolute safety in anything in life, whether that's food or driving a car or riding an airplane or walking down the street," adds Clydesdale. "That's one thing people just don't like to accept."

Barbara Kowalcyk is food safety advocate who founded the Center for Foodborne Illness Research and Prevention in 2006, five years after the death of her son Kevin from complications of an E. coli infection. Kowalcyk agrees with Clydesdale and believes that the pink slime media event was "very unfortunate. This is a company that invested a huge amount of money into food safety. I've been to the plant, I've toured it, and it's amazing the amount of money they were spending to make sure that this product is as safe as it could be."

The pristine, laboratory nature of BPI's facilities, though, is exactly what rankled the media and the masses. Where many others in the meat production chain hid their factory-like ways behind the imagery and rhetoric of the good old-fashioned family farm (just visit the meat aisle of any grocery story; the packaging invariably shows green pastures, red barns, pitchfork-laden farmhands, etc.) BPI never made that effort, mostly because its corporate customers didn't care. Its name alone shows the work it put into consumer marketing; its Wikipedia page opens with the italicized line "This article is about a company called Beef Products. For meat that comes from cattle, see beef." BPI is the anti-farm, an engineering experiment that made, without frills, a scientifically proven beef product. Which worked, until that evocative and alarming phrase pink slime was thrown at them, and they had nothing to throw back.

The public, very suddenly, was forced to confront a cognitive dissonance of its own making: People want a meat industry that is scientifically safe and efficient but also want it to feel natural and homespun. When that paradox collapsed on itself, the only way we could react was outrage. How could you keep this from us? was the underlying question. Why were the regulators and the industry allowed to make a decision about what the public should or shouldn't know about their food supply?

The answer was, in large part, Because you asked us to.

Of course, the meat industry is far from innocent. For as much as the public's distaste for animal slaughter has encouraged a "don't ask, don't tell" policy, processing plants have fought just as hard to shade themselves from the light of the public. There are the happy-cow-happy-farm rhetorical flourishes that create a false image, of course, but much more sinister has been the passing of what have become known as "veggie libel laws" across the country. These laws, on the books in 13 states, make it easy for food producers to sue critics for libel, and claim punitive damages—and make it a huge risk for reporters to even think about investigating Big Ag.

BPI filed its lawsuit in South Dakota, where libel laws allow it to claim total damages of $1.2 billion—triple the compensatory amount calculated at $400 million. If BPI wins, it will be one of the largest defamation claims ever. It would also tighten the muzzle on the press when it comes to the meat industry.

Legal experts, though, do not expect BPI to win. The closest precedent is probably the 1998 case in which Texas cattlemen sued Oprah Winfrey for defamation after the talk show host discussed mad cow disease on a 1996 episode. (At one point, she exclaimed that her guest's comments had "stopped me cold from eating another hamburger!") The suit did go all the way to trial, where Oprah won. Ultimately the Jury found that the opinions expressed on Oprah's show, though perhaps strongly stated, were based on truthful, established fact, and therefore were under the First Amendment.

"Free speech rocks," said Oprah after the verdict was handed down.

"ABC has all kinds of First Amendment protections to be able to discuss issues of public interest," says Edward Klaris, an adjunct faculty member at Columbia Law School, and legal counsel for Condé Nast. "I know that ABC will not want to settle this case, because there is a principle involved. They believe strongly that they should be able to report on these sorts of things, and to settle would be a compromise on their ideals. If they lose, they'll appeal."

There is a lot at stake, from the huge dollar amounts and financial security of an industry to the constitutional rights of the Fourth Estate to, most essentially, the safety of the public. In 2011, the CDC did a thorough analysis of food-borne illness and discovered that about 1 in 6 people (48 million) was made ill from food that year. Of those, 128,000 were hospitalized and 3,000 died.

Some experts believe there is no way for food to be both cheap and safe. But others think that goal is well within reach— if we could solve some of the problems that lie with our ability to monitor the supply. "We have a fragmented food safety oversight system that has evolved over the last 100 years and hasn't kept pace with our current production processes," says Kowalcyk. There are more than 15 agencies charged with oversight of food—a piecemeal and underfunded system that has led to poor communication.

"I think CDC, USDA and FDA do spend a lot of effort trying to talk to each other, but they probably don't do it as well as they should," says Kowalcyk. It gets worse, she adds, when you factor in the state-level health regulators, who often won't share data with the CDC because they (usually incorrectly) believe that doing so would violate the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act or would illegally publicize proprietary industry information. As a result, problems that should have been noticed earlier often go undetected until they become, undeniably, a crisis.

In 1999, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) argued that the federal food safety system needed a major revamp, writing that "it is unlikely that fundamental, long-lasting improvements in food safety will occur until food safety activities are consolidated under a single agency and the patchwork of food safety legislation is altered to make it uniform and risk-based."

Many food safety advocates feel that the single food safety agency solution is still the best option—although 15 years of fighting and nothing to show for it have left little room for optimism.

Kowalcyk believes a single agency likely won't emerge because it would require an unlikely restructuring of well-established congressional committees, so she suggests an alternative: an integrated information infrastructure that would let health officials nationwide use information better, quicker. "The goal is to get to zero food-borne illnesses," she says. "I know we're not going to get there, but that's the goal. I see food safety as a continuous improvement, but we can't have real-time monitoring without a system-wide commitment from all stakeholders to share data."

In 2011, President Barack Obama signed into law the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). Among other things, the law grants the FDA the power of mandatory recall, an authority the agency had sought for years. Unfortunately, the USDA remains limited to issuing public health alerts as a way to induce voluntary recalls of meat and poultry products. When the system works, it does so at a glacial pace.

About 19 months ago, there was a spate of Salmonella poisonings. The infections have continued, and to date, over 600 people have been made ill. The FSIS has been pointing to Foster Farms as the source of the illness, but agency officials say they have not had the evidence needed to legally ask it to recall products. Finally, on June 23, 2014, FSIS was notified of a Salmonella heidelberg illness connected directly to a Foster Farms chicken breast. The agency acted quickly, and on July 3, 2014, Foster Farms voluntarily recalled "an undetermined amount of chicken products" contaminated with Salmonella. However, these products were limited to three production dates this year: March 8, 10 and 11, only batches that the USDA and CDC could link directly to an illness. Meanwhile, additional Salmonella cases are being reported weekly, and food safety advocates, as well as U.S. Representatives Rosa DeLauro, D-Connecticut, and Louise Slaughter, D-New York (the only microbiologist in the House), have argued that all Foster Farms plants should be shut down.

But there is currently no authority that can take those types of measures—even in a public health emergency. In addition, the FSMA remains an unfunded mandate that many, including the GAO, believe does not go nearly far enough—in 2013, the GAO included revamping the food safety system on its "high-risk list."

The USDA is known to be a chronically underfunded and undermanned operation. Chris Fuller, a longtime meat processing professional, points out that if you process meat but don't slaughter any animals on-site, the USDA inspector only needs to come by once a day, for about a half hour, just to "check the paperwork and make sure it's all going properly." In contrast, an inspector has to be there every time an animal is killed. This, many say, is a prime example of a regulatory system that has been far outpaced by the industry it is monitoring. The focus on carcass-by-carcass visual inspection made sense in 1906, when the Federal Meat Inspection Act was passed, but in 2014, when a single hamburger might have meat from 75 different cows, it is no longer relevant.

The FSIS is trying to change with the times: The regulator recently proposed a new rule that would require retail outlets to keep records of the source and supplier of all materials used when mixing cuts of beef to make ground beef, for example. The FSIS is also in year 15 of a program to reduce the number of on-site inspectors at poultry processing plants by half, which it says improves safety by enabling inspectors to focus on food safety testing and not "quality assurance"—the visual inspection element, which would be put into the hands of the companies themselves. An FSIS report found that in pilot plants, Salmonella rates were 80 percent of those at non-pilot plants. The FSIS recently recommended full implementation of the program, which it says would save the cash-strapped regulator $90 million over the next three years but would also significantly speed up production lines, increasing the profit margin of the companies, all while presumably making the product safer. A similar pilot program is currently under way at pork processing plants.

But food safety advocates have expressed concern over the conflict of interest that may arise when companies police themselves—company employees may be less likely to stop the line because they are being paid by that company to keep production high. And for an already skeptical public, this appears to be letting the inmates run the asylum.

That scuffle is indicative of perhaps the most serious concern raised by many advocates of meat industry reform: The USDA can sometimes appear unsure whether its job is championing the sales of American meat, or keeping the American meat supply safe. Case in point: There are divisions of the USDA that buy and distribute huge quantities of meat (the National School Lunch Program) and that negotiate trade agreements with other countries for American beef (the Foreign Agricultural Service) and others that presumably make the hard choices to penalize poor-performing meat producers (the FSIS). Within the Agricultural Marketing Service division, a subdivision was recently formed called Food Safety and Commodity Specifications—a regulator within a marketer within a regulator. "In theory, you've got that separation within the USDA," says Jaydee Hanson, a senior policy analyst at the Center for Food Safety and Innovation. "In practice, it's pretty hard to be both the promoter and the safety inspector."

For many, the problem boils down to transparency. Everyone, from industry reps to food safety reform advocates to public servants, gave Newsweek the same advice: You should ask more questions about where your food comes from, what's in it, and why. The problem, though, is that it's in no one's best interest to answer.

One of the more striking notes of the ABC pink slime report was their statement that the USDA employee responsible for approving LFTB was Undersecretary Jo Ann Smith. Smith, after leaving public service, reportedly made about $1.2 million over 17 years serving on the board of directors of IBP Inc., which became Tyson Fresh Meats, and which has, for years, been one of BPI's principal suppliers of preprocessed meat.

There is no direct evidence to prove Smith approved LFTB. Both the USDA and BPI declined to comment on Smith's involvement (and Smith was unable to be reached for comment), although the USDA did state that in 2014, all decision letters written by the FSIS's Office of Policy and Program Development must be approved by the sitting undersecretary.

Oh, and pink slime is back. BPI has confirmed that in recent months, LFTB sales have been on the rise, although it will not give precise figures due the pending lawsuit. On August 11 2014, BPI announced it would reopen the Garden City, Kansas, location that had been closed down. Though BPI has officially endorsed the voluntary labeling of products containing LFTB, it does not package any consumer-facing goods, and so cannot control what appears on the outside of your shrink-wrapped hamburger meat. And though the USDA has endorsed voluntary labeling of LFTB, it has decided that it is not required. Worse, according to some industry insiders (who have asked to remain anonymous), other products—some less safe than their forebear—have rushed in to to fill the vacuum left by the fall of LFTB, and none of these will show up on the label either.