Rome on a late summer's day. It's hard not to wander around this hot and dusty city without thinking about cooling gelato. Italians are justifiably proud of their reputation, believing their ice cream parlours to be the best in the world.

Gelateria Alberto Pica is one of the oldest and best in Rome – and always packed. The terrace outside is crammed with dark plastic tables and chairs. My guide to this ice cream heaven was Elizabeth Minchilli, whose book, Eating Rome: Living the Good Life in the Eternal City, is soon to be published. We tasted an intriguing flavour made with rice, which I had never sampled before. It's made by soaking the rice in milk, then processing the mixture to break up the grains before sweetening and churning them to produce a creamy milk ice cream with crunchy bits of raw rice inside. Unexpected but quite delicious, and one of their specialities. It can be plain, or flavoured with cinnamon.

Rome also boasts the newcomer Carapina, originally from Florence, a modern, stylish parlour offering excellent gelati. They don't use rice, but manage to produce the same light texture.

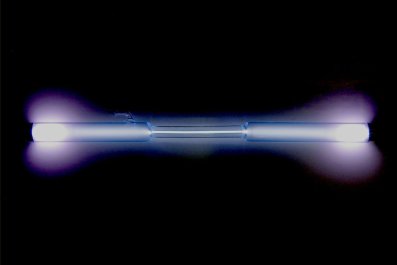

It's a common mistake to confuse ice cream with gelato. Gelato, which comes from the Latin gelatus and means "frozen" in Italian, is a specifically Italian way of making ice cream, using a low-fat milk base (anything between 3% to 5%) which is then flavoured with fruit, nuts or other ingredients. The base is often made without any stabiliser (used in ice cream to avoid ice crystals forming) and churned at low speed so that there is hardly any air incorporated. This helps keep the flavours intense.

Ice cream, however, is made with milk and/or cream, as the name indicates. As a result, it has a much higher fat content (up to 20%). It is almost always thickened with egg yolk although there is a trend now, at least in America, to thicken the base with other stabilisers such as corn starch, carrageenan (a natural seaweed extract) or guar gum (white powder extracted from guar beans). Ice cream is also churned faster to incorporate more air – some types may contain up to 50%.

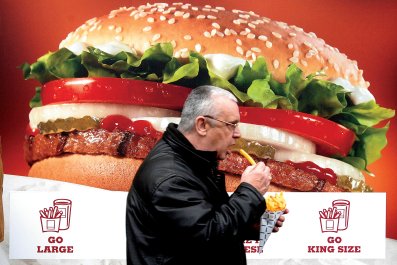

What seems like a straightforward, universal food turns out to vary widely from country to country then. Who would have thought that it had ethnic divides?

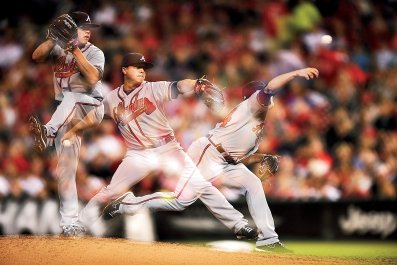

Both ice cream and gelato differ according to culture, region and method of preparation: French and American ice creams are almost always thickened with egg yolk, whereas Italians only use egg yolk for some gelati such as chocolate, vanilla and zabaglione. Otherwise the base is made without any stabiliser and because of this, it has to be churned freshly every couple of days or even on a daily basis. And when it comes to serving it, the server mashes the gelato against the walls of the container to break up the ice crystals before scooping.

It's a different story in the south. Below Rome, and in particular in Sicily, gelato is thickened with either wheat starch, cornstarch, or locust bean gum – the latter a little-known ingredient extracted from the seeds of carob trees that are native to the Mediterranean. Locust bean gum is the stabiliser used by the best Sicilian gelatieri like Antonio Cappadonia in Ceda on the western side of the island and Corrado Assenza, whose Caffe Sicilia in Noto on the eastern side is a place of pilgrimage for the sweet toothed.

Frozen desserts date back in history to the ancient Persians and Egyptians, the taste then spreading across the Middle East. They were brought to Sicily by the Arab traders who occupied the island in the 8th century and it is said that a Sicilian, Francesco Procopio Cuto, was responsible for introducing ice cream to France. Cuto is thought to have used salt and ice to create the required freezing conditions. He became the first to serve gelato in France in the late 17th century in his famous café Procope, frequented by such luminaries as Voltaire. Also according to the food historian Mary Taylor Simeti, author of Pomp and Sustenance: 25 centuries of Sicilian Food, it wasn't until the 17th century that the first description of ice cream was recorded in a poem titled "Il Candiero". Written by a Florentine, the verse describes an ice cream flavoured with jasmine and lemon made by "Il Siciliano". Jasmine granita or gelato is still a speciality of the island.

Across the Middle East and parts of the Mediterranean, ice cream is often made using a milk base thickened with salep, a fine greyish powder extracted from dried orchid bulbs, that is then flavoured with fruit, nuts or spices. Salep is little known outside Lebanon, Turkey, Syria, Iran and Greece but is quite unlike any other, with a dense chewy texture that prolongs the enjoyment.

Across India and Pakistan, the ice-cream-like kulfi is the most common frozen dessert. Thought to have originated in the Mughal Empire, pointing to its Persian origins, it is made differently from both ice cream and gelato. The milk base is boiled until it has evaporated by about half before being flavoured with cardamom, saffron, pistachio or mango.

Kulfi comes on a stick and is shaped like a long cone or else is frozen as a block and served cut into slices on a leaf. The texture is therefore creamy, but quite a different sensation from gelato or ice cream. It is often sold on the street by vendors known as kulfiwalas.

Throughout the world there is no real season for ice cream. We can eat it both during hot and cold months. In parts of Sicily, perhaps the birthplace of gelato, we have to wait until summer to enjoy it. That is, if we want the very best.