In the spring of 2009, a still-sunny President Barack Obama declared that he was bored with briefing books and, consequently, had begun Joseph O'Neill's novel Netherland in what little free time he had. This was auspicious news, and not only because his predecessor was best known for reading from The Pet Goat on 9/11 and for generally committing great violence upon the English language. By choosing O'Neill's novel, Obama was announcing that he was as worldly and sophisticated as many hoped and some feared.

The choice also hinted at refined literary tastes. Netherland, about a Dutch lawyer in Manhattan who takes up cricket in the wake of a split from his wife, is an elegy for a wounded, terrorized New York City, and also for the cosseted history-is-over world that had been, a novel that fluidly moves between the smoldering ruins of empire and the tenebrous chambers of the human heart. I was hardly the only reader who saw intimations of Fitzgerald, nor the only one who was spurred to watch many a mystifying cricket video on YouTube.

Much has gone sourly for the president since then, and I wonder if he will have time to read O'Neill's new novel, The Dog, his first since Netherland. If he doesn't get to it, what with all the Republican scuttlebutt and Mideast bloodshed, he won't have missed all that much. The novel, ONeill's fourth, succumbs to many of the pitfalls that have made the Obama presidency far more lackluster than it should have been: a tendency toward the dilatory, the inability to communicate concisely ("poor messaging," the kings of K Street call it) and a fatal lack of narrative.

The protagonist of The Dog is nameless, but might as well be a sibling of Hans van den Broek, Netherland's hero: Hans II, if you will. Hans does finance; Hans II is a lawyer. Hans is divorced; Hans II is separated from a long-term girlfriend; Hans is fully European; Hans II is half. Most tellingly, both narrate their own tales with voices urbane and lush, secret gardens in concrete jungles, voices full of plangent wisdom and dry humor and piercing observation. Netherland, at least, was full of You gotta read this lines. The Dog has them, too, though more rarely: "It may be that most lives add up, in the end, to the sum of the mistakes that cannot be corrected." To even venture such a pronouncement, in our age of tweeted little revelations, is an act of literary bravery. Too bad that such stuff isn't enough to make a great novel.

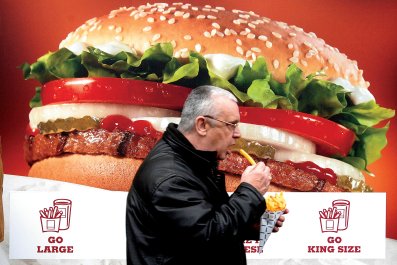

While Netherland is set in New York, where the Ireland-born O'Neill has long resided, The Dog takes place almost entirely in the tumescent desert city of Dubai, where Hans II has come to work for a Lebanese conglomerate, one of whose scions, Eddie, is an old friend. Hans II becomes a homme de confiance of the Batros Group, his daily travails largely involving deleting emails and rubber-stamping philanthropic requests.

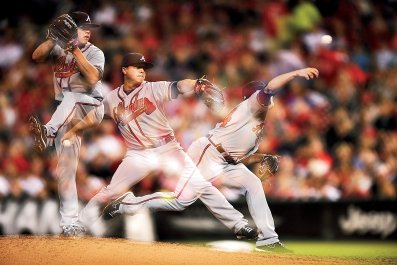

So far, I haven't alighted on a plot. That's because there really isn't one. Maybe it has to do with the search for a neighbor who may have drowned in a scuba diving accident but may also be hiding out with his second family. Maybe the plot lurks in the tension between Dubai's sleek sybaritism, never more than a text or email away, and Hans II's fruitless but irresistible dissections of why the long romance in New York failed. O'Neill, after all, does grief the way Bruegel did winter scenes. But in the Flemish paintings, there is always motion. Not so in The Dog.

Anyway, plot isn't everything, as anyone who admires The Great Gatsby knows. Netherland didn't have much of a plot, either, with Hans serving as a sort of understudy for a Brooklyn cricket "magnate." Many kinds of motion can propel a story, and it doesn't have to be of the On the Road variety. But something should happen, and it should happen to people the reader cares about. Aristotle laid out the basics in his Poetics; to transgress them successfully, as Henry Miller does in his Tropic novels, requires a ferocious escape velocity that O'Neill doesn't muster here.

The setting may have something to do with it. Actually, I suspect it has everything to do with it. In Netherland, O'Neill captured New York City as well as anyone since Tom Wolfe, and The Dog's brief sojourn there reminds you how acutely the author understands the twin engines of hubris and longing that power this city. But in Dubai, O'Neill resorts to an ironic Orientalism: He knows he is a Western observer in the East and is well aware of how fraught his position is, yet he will get as much pleasure out of that position as he can. Yes, Hans II is more nuanced in his observations than some of his fellow expats, who say things like "He's a good bloke, Sheikh Mo." But Hans II is too timid to really crack the glass facade of a place he calls "a counterattack on the natural." And so, for all of O'Neill's enviable linguistic mastery, The Dog never quite hits the bell of stranger-in-a-strange-land fiction, leaving the reader with a gracefully acerbic Fortune travelogue.

At one point, the nameless main character of this novel says that for all its growth, Dubai remains inchoate, so that you may find yourself driving on a road that suddenly ends: "Your journey fizzles out in a pile of sand." The same, sadly, is true of The Dog, a novel that is frequently beautiful but rarely goes anywhere.