An air force pilot walks into a store. The man behind the counter points at his uniform and asks: "Is that real, I mean do you ever get to fly in a war or something?" The pilot answers: "Yes, in fact I killed six Taliban in Pakistan this morning." The shopkeeper thinks it's a joke but it isn't.

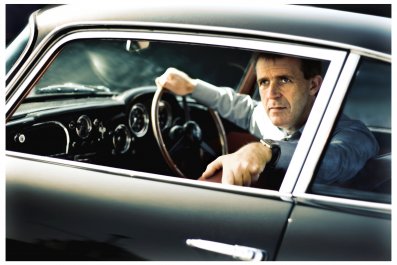

It is 2010 and America's secret drone campaign is at its height. Tom Egan (Ethan Hawke at his best) is a predator pilot. He works from a cubicle at an air force base near Las Vegas. The joystick in his hand controls an unmanned flying machine as it swoops through Waziristan.

While some of his colleagues have no qualms about remotely blasting Taliban warriors to bits ("warheads on foreheads," as one puts it), Tom is increasingly troubled. Sometimes there are civilians among the dead, women, old people and children. Tom, a former fighter pilot who risked his life in Iraq, can't help feeling both guilty and that he is a coward.

Worse than that, the horror of his job and his private life are uncomfortably juxtaposed. After his shifts in the cubicle, Tom steps into the Nevada sunshine and dashes to a suburban barbecue with his wife Molly (Mad Men's January Jones). It is a schizophrenic life that puts Tom's psyche off-kilter.

In creating this timely plot, Andrew Niccol, the writer and director of the film, will have drawn on former drone top gun Matt J Martin's account of America's "War on Terror".

In his book Predator: A Pilot's Story, Martin described civilians suddenly walking into the crosshairs. He watched, unable to stop the missile he had launched just a second ago.

There is another troubling dimension to this warfare: since no pilots need be put at risk, the bar for embarking on military conflicts has been lowered and large death tolls are more readily accepted.

Halfway through Good Kill, Niccol further ratchets up the tension. The CIA takes over the operation and orders Tom's team to kill people who merely act "suspiciously", for instance by attending the funeral of a warlord. Civilian casualties become the accepted norm: "Terrorists are known to use women and children as human shields. These combatants prove a grave enough threat to justify collateral damage," says a disembodied voice from the CIA's Langley headquarters. Tom squeezes the trigger even though he knows he is doing something morally wrong – killing hostages.

As uncomfortably realistic as the plot of Good Kill may be, Andrew Niccol decided to add a hopeful twist of humanity. Yet in the wake of a revolution in fully autonomous robotic warfare, that possibility, too, might soon disappear. In the near future, drones will become fully autonomous.

The incredible speed of their split-second manoeuvres in aerial combat will necessitate delegating the kill decision to an inbuilt software. While society is still struggling with the ethical implications of remotely piloted drones, this challenge to our moral compass may just be a war away.