In the history of confessing to strategic business blunders, Apple buying Beats Electronics might only be topped if Fidel Castro personally reopens the Havana Stock Exchange.

Society is shifting from owning music to renting it, and instead of driving that change, Apple has been stuck somewhere between missing the trend and denying that it's happening. Its reported $3.2 billion purchase of hip music service Beats smacks of an embarrassing effort to catch up.

At least one thing works in Apple's favor: No company has been able to make itself king of cloud-based subscription music. Spotify, Rhapsody, Google Music, Beats—none have truly nailed it. But somebody will, and before long, the cloud will be the dominant way people find and listen to music. The 99-cent downloaded song is about to turn into a blip on the time line of music technology—the 21st century's eight-track tape.

Just a decade ago, Apple put together the iTunes-iPod business model and defined the digital music market. For years after, Apple ruled the category the way Google rules search or Heinz rules ketchup, claiming almost 70 percent of the market and all of the gravitas. When mighty Microsoft tried to enter iTunes's territory in 2006, its Zune quickly turned into a punch line. (Funny or Die: 14 Things Nobody Has Ever Said About a Microsoft Zune. No. 1: "Oh, you have a Zune, too?")

But then Apple froze. It held on to a deep cultural bias in favor of 99-cent downloads, nurtured in part by its own success, and in part by the legacy of Steve Jobs, who pointedly said that subscription services "treat you like a criminal. We think subscriptions are the wrong path. We think people want to own their music."

Along with being wrong in the long run in this category, Apple failed to invest in its own kingdom. As a music player and store, iTunes has barely changed in 11 years. Ben Easton of New York nightclub Joe's Pub derided iTunes as "a spreadsheet with music." By last year, Apple's share of digital music had slipped to 63 percent and is expected to fall further. "It's a classic case of category neglect," says Al Ramadan of tech positioning firm Play Bigger Advisors. "They got a little fat, dumb and happy. They didn't create a blueprint beyond current products."

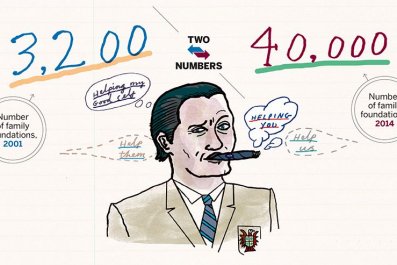

Granted, music subscription services have been around for a long time, with little impact. RealNetworks launched Rhapsody back in 2001. The public for the most part didn't get the idea of renting music. It was too big a leap from the age-old practice of buying records and then CDs. You always either paid for music and owned it, or you experienced it for free on the radio. Something in between seemed too weird. Owning certain albums, in fact, became part of your identity—you were the kind of person who owned a Clash album. The 99-cent download was the right intermediate step at the dawn of broadband Internet.

But in the past few years, important things changed. One was the explosion of smartphones and tablets. We started to have lots of gadgets that would play music. Synchronizing downloads got increasingly knotty.

At the same time, the cloud went mainstream, and we liked the idea that software, content and services were available anywhere, anytime, over ubiquitous wireless networks. Music in the cloud became easier to access and nearly as reliable as a song on a hard drive.

Finally, social networks made us want to share music and playlists with far-flung friends. Spotify, a latecomer to cloud music, latched on to that trend and exploited it. Apple never figured out how to make this work well with iTunes.

Oh, and here is a hard to ignore fact: Cloud music is cheaper. On some services, if you put up with ads, the music comes free. The combination of all this sets up cloud music to stomp on iTunes like Godzilla on a constitutional through Tokyo.

Cloud music is particularly appealing to anyone born after about 1985. "Consumers who didn't grow up with physical media don't value ownership so much as access," says Larry Downes, co-author of Big Bang Disruption, which describes exactly the squeeze Apple is facing. "For them, the cloud-based model works better."

Downloads are still a much bigger business than cloud music, but the shift is on. In 2013, revenues from downloads globally fell 2 percent, according to music industry group IFPI. Cloud services grew 51 percent and passed $1 billion in revenue. About 28 million people now pay for a music subscription, up from just 8 million in 2010.

You can see where this is going: cloud up; downloads down. In another five years, you're going to wonder why you have all those song files eating up your digital storage, much the way you questioned the wisdom of your bookshelf full of CDs a half-decade ago.

In 2020, Apple will still be king of the digital download, but that will be like congratulating Barnes & Noble because it's king of physical bookstores.

The question now is: Who is going to define and rule the cloud music category? The IFPI says there are around 450 cloud music services globally. We don't want that many choices. Most of us want one great music service—the best one, the one with all the best music, the one with the clout to get good music first, the one all our friends use so you can send them favorite songs and playlists, the one you can use in almost any country. That king doesn't yet exist.

Apple could do it, but not with its wimpy little me-too offerings like iRadio. That's why it needed to buy Beats or something like it. Apple is at its best when it defines a new market and installs itself as king: iPod, iTunes, iPhone, iPad. It can even come to a market late and do that. There were smartphones before the iPhone. But Apple has no history of buying its way into defining a market. This could be a first.

Consumers should hope someone—anyone—breaks through and defines and leads the cloud music category. Cloud music needs this the way social networking needed Facebook, streaming movies needed Netflix and e-books needed Amazon's Kindle. Then, for the first time since Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, the renting of music will finally push owning music into obsolescence.