Most people know less about their doctor than they do about their local barista or bartender. The world of medicine—from the pediatrician checking your child's breathing to the specialist researcher toiling away at a university lab—is guardedly private, hidden behind spotless white coats and inscrutable clipboards. But that's about to change.

Starting September 30, Jane and Joe Citizen will be able to search a government-run website and see all the consulting fees, stock options and trips to Key West given by pharmaceutical companies to primary care physicians, ob/gyns, dermatologists and other doctors. Referred to as the "Sunshine Act," this transparency clause in the Affordable Care Act allows the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to publicly post all payments and other valuables given by Big Pharma to physicians and teaching hospitals.

Some doctors can't hide their glee. "Conflicts of interest and financial relationships between drug companies are ubiquitous in almost every single aspect of medical practice and medical research and medical education in the U.S.," Eric Campbell of Massachusetts General Hospital tells Newsweek.

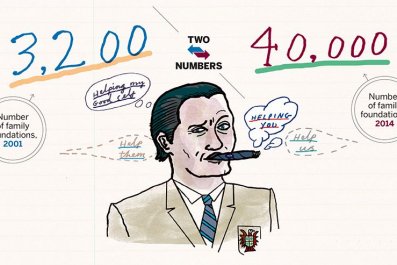

Campbell has been on the trail of potentially unethical behavior for some years. In 2004, he and his colleagues surveyed 140 institutions—125 medical schools and the 15 largest independent teaching hospitals in the U.S.—and discovered that 60 percent of department chairs had some form of personal relationship with the pharmaceutical industry. This included serving in a variety of positions: consultant, member of a scientific advisory board, paid speaker, officer or a member of the board of directors. At the institutional level, two-thirds of the departmental units were firmly obligated to the industry by way of research equipment, unrestricted funds, residency or fellowship training support, continuing medical education support and funding from intellectual property licensing.

"It's actually hard to find areas where people don't have a frequent and often very lucrative financial relationship," Campbell says.

How lucrative? One study, published in March 2014 in The Journal of American Medical Association, found that nearly 40 percent of the 50 largest pharmaceutical companies had academic medical center leaders sitting on their boards. The annual compensation for these directors is over a quarter of a million dollars, on average. "These individuals have a fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders as members of the board, and that's a very different relationship to a pharmaceutical company than just consulting," says Walid F. Gellad, an assistant professor at University of Pittsburgh's School of Medicine and author of the study.

Holding a leadership position at an academic medical center brings considerable influence over research, clinical and educational missions. And when one of these medical center leaders is also charged with providing stewardship for a profit-making business, it represents a substantial conflict of interest.

The issue is not the fact that conflicts exist—it is inevitable that doctors work closely with Big Pharma. The key, says Etta D. Pisano of the Medical University of South Carolina, is how to bring transparency to the process. The public, and individual patients specifically, should be able to know and understand a doctor's contacts and contracts with the industry—particularly those that edge toward the unethical.

Those unseen and improper affiliations may be rampant. Campbell cites the latest troubles of GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Britain's biggest drugmaker. In the summer of 2013, Chinese authorities accused GSK of bribing doctors and officials to the tune of $483 million. Earlier this month, GSK faced investigations for alleged bribery in both Poland and Iraq.

GSK isn't the only one. "If you look at the record of drug companies being in settlement with the federal government for doing some really bad things like breaking the law, bribing doctors, it's every major drug company in the last five years," says Campbell. "And many of them are repeat offenders."

The cautionary tale of Vioxx shows how the entanglement of Big Pharma and research can lead to a public health disaster. Vioxx was approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a painkiller in 1999. But soon after, reports came in that the drug had catastrophic side effects; according to FDA estimates, between 38,000 and 140,000 patients had heart attacks and strokes induced by Vioxx, and 30 to 40 percent of those people died.

After Merck recalled the popular drug in 2004, the Justice Department brought charges against Merck, alleging that it illegally promoted a misbranded drug while deceiving the government about its safety profile. Merck pleaded guilty to both criminal and civil charges, paying the government $950 million to resolve all of them. Additionally, Merck settled a class-action lawsuit, paying nearly $5 billion to consumer claimants. (As large a sum as that is, it didn't hurt the company's bottom line. Merck recorded more than $11 billion in sales of Vioxx from mid-1999 to September 2004, according to The Wall Street Journal.)

During the legal battles, it came out that some people charged with investigating the drug's safety during human trials may have known about the dangers of Vioxx soon after it reached the market. Dr. Michael Weinblatt of Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, chaired the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) of the Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research (VIGOR) study, a five-person committee responsible for monitoring the safetyof the VIGOR study and determining when it should end. During the time period allotted for the DSMB to perform its duties, adverse cardiovascular events were reported: twice as many patients taking Vioxx had heart problems or died, compared with the control patients on the well-documented nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac. The DSMB did not have direct power to keep Vioxx from the market, and in fact, Weinblatt insisted that Merck further investigate the higher cardiovascular risk. According to NPR, Merck responded with a proposal that they analyze any heart problems discovered by a cut-off date, one month before the planned trial end-date.

Weinblatt agreed to the plan. NPR reports that soon after, he signed a new consulting agreement that would pay him a maximum of $5,000 a day for 12 days over a 2-year period to sit on a Merck advisory board. Weinblatt says he ultimately received $20,000 in compensation for his work on the board.

Dr. Curt Furberg, a professor of public health at Wake Forest University, told NPR that "You can see it as a payback for being a loyal, supportive investigator. It just looks bad."

Because of the cut-off-date, three of the 20 heart attacks that occurred during the VIGOR study did not appear in the published paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, though the paper did reference a statistical increase in cardiac events in the Vioxx. Ultimately, Vioxx —appearing safer than it actually was — remained on the market.

"It was incumbent on the watchdog committee to stop the trial, to alert the responsible parties and the public," Dr. Eric Topol, a cardiologist currently serving as Director of the Scripps Translation Science Institute, told NPR.

At the time, Weinblatt held $72,975 of Merck stock, a fact which was publicly disclosed. In an email, Weinblatt tells Newsweek that this was, at the time, less than 2 percent of he and his wife's total investments. Winblatt also writes "the ownership of Merck stock did not influence my activities on the DMB. There is no direct evidence that Weinblatt was influenced by these stockholdings, or by the consulting contract he received after the end of the trial. But in 2006, concerns were raised by many of Weinblatt's contemporaries. Drummond Rennie, Deputy Editor of JAMA and professor at the University of California, San Francisco, told NPR: "That is more than enough money to influence somebody unconsciously, and perhaps even consciously. And that sum of money makes that person no longer independent. And if you're not independent, you shouldn't be on the DSMB." Social scientists have found that even what most people would consider small, ethically acceptable gifts can influence behavior, as can gifts given without explicit demands

Weinblatt defended himself to NPR, stating, "I deeply resent the suggestion that there was any conflict of interest between my brief service on the advisory board and my work as chair of [the safety committee for VIGOR]."

In his email to Newsweek, Weinblatt writes that "I do not agree with the opinion of 'outside experts' about the decision by the five members of the DSMB to not discontinue the study. Our decision was based on the data in the study and that this cardiac signal had not been previously seen in other randomized studies. It should be pointed out that this was an event based study and the study was extremely close to completion at the time of the DSMB review of the cardiac events."

Pharmaceutical companies have made handing out many small gifts an intrinsic part of their business. In 2012, the industry spent more than $27 billion on the promotion of its products. To market drugs, companies use a variety of methods, including what they call "detailing"—face-to-face promotional activities directed toward physicians as well as pharmacy directors. This may include taking doctors out for meals and giving them gifts in the form of medical textbooks.

Providing free samples to physicians is another part of routine company marketing costs. Doctors prefer to believe they are helping their poorer patients when they accept and pass along these free samples. Besides the obvious conflict of interest there, their patients ultimately end up paying higher overall prescription costs because doctors often feel compelled to prescribe the sampled drug rather than a less-expensive generic alternative. Pharmaceutical companies also host meetings and pay physicians substantial speaker fees to discuss the use of particular drugs.

"[There has been a] completely institutionalized form of payola—an underground economy in medicine—for years," Campbell says. "Doctors and institutions have benefited from many of these relationships for a long time…. They see absolutely nothing is wrong with them. Many of them see it as their right."

The best we can do, Pisano says, is get doctors to act as "honest brokers for the public" and develop a "framework by which [doctors] don't become essentially owned by" the drug companies. She has collaborated with physicians Robert N. Golden and Laura Schweitzer to formulate rules that would allow doctors to more ethically meet the challenge of working with the pharmaceutical industry. "I was sort of shocked when I went to look if there was anything in the literature about how one should structure their relationship with industry as one moves up the chain…and there was nothing there," she says. "So we wrote it."

Their policy suggestions are just that for now, and they will likely stay that way. Government regulators are loath to join the fray on this issue, and the Supreme Court has ruled that state laws banning pharmaceutical gifts are in violation of the First Amendment. As a result, every academic institution is left to develop and enforce its own policies. However, there is a good chance that the Sunshine Act could push administrators of academic medical centers to institute the recommendations of Pisano and her team, even if there's no law on the books to make them. After all, there will soon be plenty of the raw data needed by researchers (and journalists) to bring to light the sometimes sordid details of the relationship between the pharma lab and the doctor's office.

Perhaps more important, individuals could use that knowledge to make informed decisions about where to take their health care business. The data could even be integrated into doctor reviews and rating systems. Given the ability of tools like Yelp to make or break businesses, the Sunshine Act may help the market drive better practices: If the American public chooses ethical doctors more often, more doctors will act ethically.

A previous version of this article stated that Michael Weinblatt chaired the VIGOR study. He actually chaired the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) of the VIGOR study. The DSMB was responsible for monitoring the safety and outcome events, and for making periodic recommendations to the steering committee about whether to terminate or continue the study. It also incorrectly stated that Weinblatt chose not to investigate the problems uncovered in the VIGOR study. In fact, Weinblatt did ask for further investigation of the higher cardiovascular risk.