On London's Wigmore Street, a musical event of global proportions is taking place. When it ends next month, a minimum of $45 million will have changed hands. Buyers are bidding on the world's most exclusive instrument, a viola made by 17th century Italian master Antonio Stradivari.

That's around $28 million more than the previous record-holding instrument—a violin—fetched in a private transaction two years ago, and $29 million more than the previous auction record, held by a Stradivarius violin sold in 2011.

The three instruments are not the only ones performing well. According to research by London instrument dealer Florian Leonhard, for the past decade the average Stradivarius has seen its annual price increase by 10.9 percent, and some instruments have recorded up to 20 percent.

"Rare instruments are a steady investment with no dips," explains Tim Ingles, whose firm, Ingles & Hayday, is handling the auction in conjunction with Sotheby's. "In 2008, when people who owned stocks and property were panicking, Stradivarius owners were not. In fact, people realized that rare instruments are a safe investment."

Still, $45 million is a phenomenal leap from the previous record. That's because the MacDonald, as the instrument is called, is not just the Mona Lisa of musical instruments; it's also a viola.

"The huge majority of Stradivari instruments are violins, so buying one is not that difficult," explains Ingles. "You may just have to wait a couple of years." Some 650 of Stradivari's 1,100 string instruments survive, as do 150 of the 250 violins made by his equally famous contemporary, Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù.

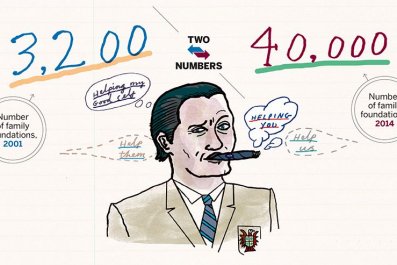

Unlike in the past, when foundations would usually buy instruments to make them available to musicians, today's buyers are often investors. "Nonmusicians collecting rare violins is nothing new," notes Leonhard, a leading authority on instrument values. "The difference is that now there are major collectors all over the world. Today, collecting instruments is a way of making your name, and it has made high-net-worth individuals interested in collecting."

One collector, Silicon Valley millionaire David Fulton, owns close to 20 instruments made by Stradivari and Guarneri. London banker Jonathan Moulds also owns several Stradivariuses and Guarneris, which he says have tripled in value over 15 years. Both Fulton and Moulds are accomplished amateur musicians, but Ingles' and Leonhard's clients also include hedge funds and individuals with little interest in music.

There are other advantages of the instrument business for investors of a certain sort. The trade is not only esoteric but unregulated. Because dealers usually also evaluate the instruments, there can be conflicts of interest.

Dealers like Ingles and Leonhard enjoy worldwide respect, but two years ago another leading dealer was sentenced to six years in prison for fraud. Vienna-based Dietmar Machold embezzled tens of millions of dollars by telling clients their rare violins were worth a modest sum, then sold them for a much larger amount, pocketing the difference.

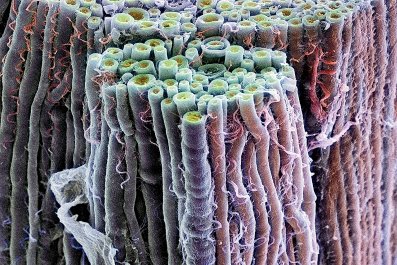

Adding to the mystery of a Stradivarius's or Guarneri's value is a scientific experiment earlier this year. In a blind test involving several Stradivariuses and modern instruments, a group of established violinists were asked to pick the violin whose sound they most liked. The majority chose a modern instrument. And when asked to identify a modern violin and a Stradivarius, the majority guessed incorrectly.

Yet such reports don't seem to deter buyers. Francesca Peterlongo, who heads a major musical foundation in Italy, says: "The reason that Stradivari and Guarneri are so expensive is not just that they're famous brands and that there are so few of them, but also that famous musicians have played them. Buyers want to be able to say, 'I have the violin Itzhak Perlman used to play.'"

But the rush is leaving musicians in a precarious situation. "The competition from private collectors and investors has pushed many musicians out of the market," notes Evan Rothstein, deputy head of strings at London's Guildhall School of Music. "Still, as important as the greatest instruments can be, the most talented artists will always manage to make their voice heard through their expressive creativity."

And some philanthropic-minded buyers actively help further players' careers by lending them instruments. It is not necessarily an altruistic gesture. If the borrower is famous, the instrument's value increases.

American cellist Joshua Roman, who plays a borrowed Stradivarius once used by the legendary cellist Jacqueline du Pré, has some sympathy for the buyers. "Even if they're willing to lend you an instrument, the insurance makes it very difficult," he says. "The insurance companies have very strict rules, for example requiring the instrument to have a burglar alarm and a fire alarm. And they get nervous if you travel with the instrument."

The Stradivari instruments' financial success is having a knock-on effect on less famous violins. Indeed, instruments may be the new Jackson Pollock, a trendy niche where enormously wealthy people can park their money and enhance their reputation in the process.

Yet Leonhard insists that is not what is happening with vintage instruments. "Artists like Pollock are fashion-driven. He drilled a hole in his paint cans, hung them from the ceiling and let them drip and called it art. The interest in such art can change quickly, but that's not the case with violins. A Stradivari is a solid piece that has existed for hundreds of years."

Still, the investor interest in instruments closely resembles that in visual art. In that comparison, the elaborate boxes of wood made in workshops in 17th and 18th century Cremona in northern Italy remain a bargain. Notes Ingles: "If you call the MacDonald the Mona Lisa of the instrument world, yes, then you can say that it's undervalued. But there's a bigger market for visual art than for instruments."