Most people think carefully before entering Syria, where one of the world's deadliest conflicts rages. Many will not enter at all; some war correspondents refuse to work there because of the risk of kidnapping.

Richard van As was unconcerned. "I was excited to come," he says. "I guess I was bored."

Van As is no danger-addicted war tourist. He traveled from his home in Johannesburg, South Africa, to establish labs that could fit victims of the fighting in Syria with low-cost prosthetic hands and arms he designed.

His flippant dismissal of the risks, however, is typical of a man that his former collaborator, Mick Ebeling, describes as "the most compassionate yet crazy guy you'll ever meet."

Van As's trip involved dodging shells and gunfire and passing through checkpoints manned by extremist militants, but he returned to Turkey with nothing worse than food poisoning. One evening, he sat at dinner next to a member of Al-Qaeda's Syrian wing, Jabhat al-Nusra. The following day, he discovered the fighter had been wearing an explosive suicide vest.

The new technology was installed in two existing surgical centers run by the National Syrian Project for Prosthetic Limbs (NSPPL). One is on the outskirts of the Turkish border town of Reyhanli, another a few miles away in Hazano, Syria, in the Idlib province—in the northern part of the country that is controlled by rebel forces opposed to Syrian President Bashar Assad. A private aid organization, Every Syrian, paid the $60,000 costs.

Prosthetics technology has been a very personal cause for van As since he himself lost four fingers in a carpentry accident in 2011. "When I cut off my fingers, I made it my business to know what's going on in there, gathered information, read and researched," he explains. He quickly discovered that prosthetics were incredibly expensive—tens of thousands of dollars—so he decided to engineer replacements for himself and others.

"I wasn't happy with the way people were treated and the cost. I wanted to help," he says. Working with U.S.-based designer Ivan Owen, he developed new fingers for himself, then built a hand and fingers for a 5-year-old boy.

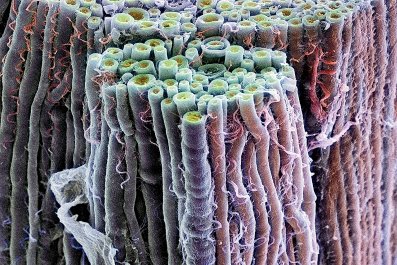

The project resulted in the launch in January 2012 of a company van As christened Robohand, which so far has made more than 200 mechanical fingers, hands and arms. The 3-D printers are used to create parts from the thermoplastic polylactide, which are combined with aluminum pieces. The prosthetics respond to user stimulus via movement of whichever joint—wrist, elbow or shoulder—the patient still possesses, and require no electronics.

Every Syrian's funding will allow NSPPL to make around 150 prosthetics that cost about $400 each. Manufacturing time will be around 10 hours per hand, says a member of Every Syrian who asked to be called "Abu Faisal" for the safety of his family still in Syria.

The hands are durable, too. It is too early to be sure of their lifespan, says van As, but those made when the company was founded are still going strong.

Van As operates Robohand on a semi-charitable basis so that those who cannot pay are essentially subsidized by those—such as customers in wealthy countries—who can. He also made the firm's designs available on an open source basis, so people with a printer can make their own. Other prosthetic manufacturers, he says, were not happy at his actions.

It is not hard to imagine van As infuriating people. He is impatient, brash, swears constantly, particularly when disparaging overly academic terminology and attitudes, and he smokes.

The devastation he witnessed in Syria affected him. "This war is senseless," he says, looking out into the Idlib hills from the Turkish side of the border. "It's brothers against brothers."

The toll wreaked on the country has been enormous. As many as 20,000 Syrians of all ages may have lost limbs, according to NSPPL board member Dr. Mahrous Alsoud.

The project at first decided to provide only legs to the limbless; they are far cheaper than high-tech prosthetic arms and more functional than low-priced but purely cosmetic upper limb replacements. But as word of the clinics spread, many who had lost hands or arms began making the expensive and risky journey in the hope of regaining limbs.

"We were hesitant to start [producing hand and arm prosthetics]," says Alsoud, "[but] we realized that Robohand could be a solution for a durable, affordable arm which could actually restore some function."

The project began when Faisal contacted van As via Facebook. "We asked if we could send someone to train with Richard, but he told us it was a waste of time and he'd come to Syria himself," Faisal recalls.

Van As has taken his technology across the world, working with aid organizations and commercial ventures. At the end of last year, Ebeling headed a mission to set up a Robohand clinic in South Sudan's Nuba Mountains to make prosthetics for victims of that civil war.

He was trained by van As and in turn taught eight young local men how to produce the limbs. They learned quickly, Ebeling says, a testament to what he describes as the "simplicity and brilliance" of the Robohand design. Filmmaker Adrian Belic, who also accompanied van As into Syria, documented the project.

The South Sudanese lab quickly began producing an arm a week, Ebeling says, and remains operational, despite a short hiatus in December when fighting flared up.

But Syria involves an entirely new level of risk. Van As's decision to go there himself was based not on politics but on need, he says. "If the regime had asked me to come, I'd go. And if Al-Qaeda called, I'd go too. Each side is shooting the other's legs and arms off. I don't care what race, creed or class you are, everyone has a right to be helped."

Perhaps predictably, things did not quite go according to plan. The 1,100 pounds of gear van As shipped to Turkey—including four 3-D printers and two solar panels—were soon snared in red tape, then impounded for weeks in customs in Adana Airport.

Van As brought some equipment with him when he traveled—a smaller printer and some materials—and took them to the Hazano clinic. There, he trained a prosthetic technician, Abdul Rahim, to make the first Robohand manufactured on Syrian soil.

The main equipment's shipment was still stuck in bureaucracy when the team got back to Turkey, so Every Syrian arranged for customs to drop the cargo in the "no man's land" on the Turkish-Syrian border. There, it was labeled as faulty to get past border guards, and NSPPL staff brought it back to the clinic bit by bit.

The first printer arrived at the Reyhanli clinic a few hours before van As left for South Africa, giving him just enough time to set up Robohand production. It should be fully operational soon. Rahim says he is confident he can make a hand by himself and teach others.

Despite the inevitable vagaries of war and import procedures, the effort in Syria is considered a success. Before he left for South Africa, van As, who had been constantly edgy and restless, suddenly relaxed. It had not been, he reflected, a bad week's work after all.