Mixed signals are coming out of the Muslim Middle East. Some experts believe the region is about to burst into a regionwide sectarian bloodbath, the likes of which we have not witnessed in centuries.

Yet the Persian Gulf's two powerhouses that have been at each other's throats for decades, Saudi Arabia and Iran, are trying to kiss and make up.

In a move that stunned analysts and made diplomats do a double take, the Saudi foreign minister, Prince Saud al-Faisal, has invited his Iranian counterpart, Mohammed Javad Zarif, to visit the Saudi capital, Riyadh. Zarif quickly accepted. But the Iranian foreign ministry said late last week that "preparations" are needed and that topics must be decided before a date for the visit can be announced.

The depth of animosity that pits Saudi Arabia, leader of the region's Sunnis, against Iran, the most powerful Shiite nation, is so deep that few in the region believe the meeting will lead to an agreement between them. Some even fear it may lead to an escalation of hostilities.

The Iranians, after all, cannot even accommodate the Saudi name for the body of water that separates the two countries. In 2010, Tehran announced it would deny access to its airspace to any airline that, even in an in-flight film, would sanction the words "Arabian Gulf" (as opposed to the Tehran-approved "Persian Gulf").

"There is very little of substance for these two to agree upon, except for platitudes about the need to improve security in the Gulf, and perhaps some token economic trade exchanges and pollution in the Gulf," says David Crist, a Middle East historian on leave from the U.S. Department of Defense.

The Saudi kingdom, Crist says, "is paranoid about the growth of Iranian influence. And the two are on the brink of a covert war." The danger, he adds, is "if their covert conflict escalates into a more open conflict. These talks may be a way of trying to head off that sort of escalation, [because] the entire region is on the brink of a sectarian conflict the likes [of which] we have not seen since the 17th century."

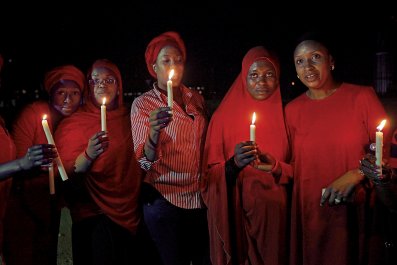

The civil war in Syria is a proxy battle of wills between the Sunni and Shiite factions of Islam. Similar battles rage in Bahrain, Yemen, Lebanon, Iraq and elsewhere. Riyadh and Tehran play major roles in pulling the sectarian strings behind these battles. In addition, Riyadh leads a regional front trying to block Iran's progress toward building its own nuclear weapons, while hinting that if Iran becomes a nuclear power, so will Saudi Arabia.

So far, the Saudis appear to be losing in Syria. Three years into the region's most deadly civil war, the Tehran-backed Syrian president, Bashar Assad, who leads the Alawite minority—a Shia offshoot—that has ruled Damascus for decades, is seen by many in the region as the victor.

Meanwhile, as talks between six world powers and Iran resumed last week in Vienna over Iran's nuclear program, Iran is widely seen as getting dangerously close to realizing its goal of becoming a nuclear power whenever it chooses and will use that new muscle to dominate the region.

"The Saudis are frustrated," an Arab diplomat who has recently returned from Riyadh told me, speaking on condition of anonymity. "They feel that their side is losing in Syria, and for them it's personal. They fought to get Assad out, and he's surviving. They also fear that Iran's nuclear stance will prevail. And they blame the Americans for all of this."

Saudi officials made public their disappointment over Washington's failure to intervene in Syria after President Barack Obama's "red line" over the use of chemical weapons was crossed by the Assad regime. They have also warned that similar firm positions on preventing Iran from becoming a nuclear power are also eroding fast. Obama's recent visit to Riyadh, according to several diplomatic sources, failed to ameliorate such suspicions.

In connecting directly with Iran, the Saudis are, perhaps, trying something new. "There have been talks about the desire to revive communication between the two countries, which was expressed by Iranian officials," al-Faisal said earlier this month. "Any time that [Zarif] sees fit to come, we are willing to receive him."

The move puzzled even Riyadh's best-connected citizens. Relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran are "now the worst they have been in 30 years," Abdul-Rahman al-Rashed wrote in the Saudi-backed, London-based newspaper Asharq al-Awsat. "I think Iran is not yet ready for any reconciliation," he added.

Al-Rashed, general manager of the Saudi-financed cable TV network Al-Arabiya, fretted that such talks may not bode well for Riyadh. "Saudi Arabia will be the weaker party at any potential negotiation table," he wrote. Negotiating will strengthen Iran's hawks and "send the wrong message to a number of Arab countries fighting Iranian proxies." They will also seal "American officials' conviction regarding the importance of cooperating with Iran," al-Rashed wrote.

The Saudi invitation came soon after major personnel changes were made at the top in Riyadh. Two relatively young princes, Muqrin bin Abdulaziz who was named second in line to the throne, and Mohammed bin Nayef, the interior minister, moved up, while longtime stalwarts of the kingdom were pushed aside.

Much more significant, however, may be the internal tensions across the Gulf in Tehran. There, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps is challenging President Hassan Rouhani and his allies over power, policy and the general direction of the country's Islamic revolution.

Menashe Amir, director of Israel Radio's Farsi service, which is widely listened to inside Iran, says the Rouhani camp insists on opening Iran to the outside world, believing the Islamic Republic will not last unless international sanctions are lifted and ties with Iran's neighbors are allowed to normalize. The hardline guards, meanwhile, fear the Islamic regime will collapse if Iran allows outside influences into the country.

Rouhani's mentor, former president Mohammad Khatami, "was a coward who declined to confront the guards," says Amir. "Rouhani, on the other hand, is taking them on. He may not have enough power to win, but at least he's bravely trying."

Ali Alfoneh, an Iran watcher at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies in Washington, D.C., notes that Rouhani's government has canceled funding for a number of civilian projects that in the past have been awarded to the guards. And the internal struggle, Alfoneh says, could affect negotiations with the Saudis because "the Revolutionary Guards have everything to lose if there is an agreement."

The guards strictly adhere to the writings of the revolution's founder, Ayatollah Khomeini, who vowed half a century ago to end the hold the royal Saud family has over the whole of the Arabian peninsula. Meanwhile, as Crist notes, the Saudis see Iran as the "head of the snake" that needs cutting.

Crist, now a visiting fellow at the Washington Institute, notes that this is not the first time the two countries have tried to improve relations. One attempt ended badly in 1996: While Iranian diplomats tried to negotiate with their counterparts in Riyadh, an Iranian-backed terrorist group in Saudi Arabia bombed the Khobar Towers complex, where American and other foreign troops were stationed.

Instead of heralding a new age of peace and understanding, the impending Saudi-Iranian powwow may trigger more violence. The Revolutionary Guards may decide once more to undermine the talks by mounting another savage attack on Saudi soil. Or, says Crist, the two sides may turn their proxy conflict into an all-out war, possibly in an unexpected place—like Iraq.