Just don't mention cheese sauce. Once the mainstay of school dinners, cauliflower is leaving the canteen to enjoy something of a makeover – even if you have to hold your nose at times. Not only is it appearing in all the most elegant restaurants, but it is also pushing broccoli out of the way to be lauded as a superfood.

Until recently, broccoli was the best known of the brassica superfoods, including cabbage and kale. Yet recent studies show that its fellow cruciferous, cauliflower, has just as much goodness as broccoli – and perhaps even more. It's richer in vitamins than other brassicas, with the orange variety having 25 times more vitamin A than the white. Yet white is good, too. Scientists who carried out experiments feeding white cauliflower to mice and rats believe that compounds released during digestion could potentially protect cells from DNA damage in human beings.

This alone is a good reason to have cauliflower on the menu, preparing it following traditional recipes or more innovative -- Mark Twain called the cauliflower a "cabbage with a college education" and it certainly lends itself to sophisticated treatment.

Regardless of its health benefits, it has always been part of my diet. And more so now that it is centre stage on menus from London to New York to San Francisco, either cut across in thick slices and served as a steak, or its florets crumbled to produce a gluten-free couscous, or ground very fine for a pizza base. These are only a few of the myriad new ways that chefs using to turn the cauliflower into a sexy vegetable.

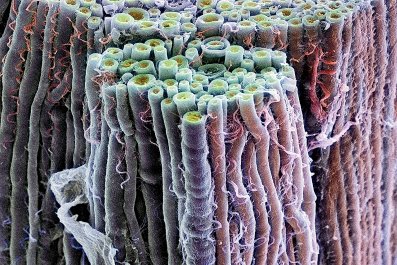

Not bad for a vegetable that's actually physically challenged. It is a variety of cabbage, where the normal development of flower and stalk is arrested, causing a proliferation of the immature flowering tissues that then accumulate into large masses. So it's a developmentally-arrested flower structure.

The white cauliflower is the most common. Farmers retain its milky colour by tying leaves over its head as it grows to hide it from the sun. According to Jane Grigson, the author of the classic Vegetable Book, its origins lie in the Arab world. She quotes John Evelyn as writing in 1699 that the best seeds came from Aleppo. Another theory is that cauliflower could have been introduced into Europe from Cyprus, as its French name, chou de Chypre, may indicate. In either case, it became known in Europe from the 16th century onwards-- for much of that time baked, boiled, or steamed. It was not until contemporary chefs began experimenting that its versatility was appreciated in the west.

Not so in the Mediterranean, Middle East and India. Palestinians for example, layer cauliflower and other vegetables with rice to produce one of their most iconic dishes, maqlubeh, in which rice and vegetables are turned out of the pan onto a platter in the shape of a cake. In Lebanon and Syria, the florets are fried until crisp and served with a tahini dip as part of a mezze spread; in Sicily the local green winter cauliflower is first boiled then cooked into a mush in olive oil with a little onion, anchovies, raisins and pine nuts and seasoned with saffron to produce a delectable thick sauce for pasta. I had the latter recently cooked for me at the height of the season by Mary Taylor Simeti, author of the magisterial volume, Pomp and Sustenance: Twenty-five Centuries of Sicilian Food. In her book she advises readers to eat it when in season. In the Sicilian climate, she says: "After Easter, both sermons and cauliflowers lose their flavour." She also cites a dish from Apicius, a collection of Roman recipes, calling for cauliflower "covered with boiled spelt (a variety of wheat) and pine nuts sprinkled with raisins," that could be the ancestor of her Sicilian classic.

Cauliflower is one of the most important winter vegetables in India, essential to both meat eaters and vegetarians, used in curries, soups and pickles and made into fritters or simply stir-fried in a spicy paste. It can also be grated and mixed with onions, fresh herbs and spices to make a Punjabi-style filling for paratha, (a flat bread cooked over a griddle). Given all this variety, I wonder why it took today's top chefs so long to start appreciating this humble vegetable and for farmers to begin growing the colourful hybrids that are now found in farmers markets.

Soon, I will be eating at Dan Barber's Blue Hill restaurant in New York City for the first time. One of the gurus of vegetable cooking, he has developed his version of cauliflower steak. He first 'milk-pickles' then cooks sous-vide (in vacuum conditions) before searing it. A rather complicated method. Similarly, the food scientist and author, Harold McGee, gives the following advice to prepare the ultimate cauliflower. He suggests pre-cooking it for 20 to 30 minutes in an oven pre-heated to 55-60C (130-140F) before boiling it so that it can develop a "persistent firmness" that will allow the cauliflower to survive "prolonged final cooking". I will follow McGee's advice from now on given that he is the pre-eminent among food scientists. I will also attempt to emulate Dan Barber in my kitchen.

Another less complicated option is to simply eat cauliflower raw. Slice the florets thinly using a mandolin and arrange them on a plate around a subtle Palestinian pumpkin dip. Then sprinkle with Aleppo pepper. Both dip and pepper add to the health benefits: pumpkin has very high levels of beta-cryptoxanthin, which is thought to reduce the risk of inflammatory diseases, while Aleppo pepper is said to be a rich source of vitamin A, fibres and anti-oxidants. Not only a dainty dish, but also healthy.