Updated | In the early hours of February 17, three teenagers from East London slipped out of their parents' homes and caught a flight to Istanbul. After arriving, they waited for 18 hours at a Turkish bus station before crossing the border into Syria. The Islamic State, better known as ISIS, had successfully lured them into a war zone.

The three teens aren't the first foreigners to join ISIS, and they won't be the last. According to recent estimates, roughly 20,000 foreigners have joined the conflict in Iraq and Syria. Of those, 3,400 are from the West, and many are young Muslims. Driving this recruitment effort is ISIS's slick social media campaign, which features selfies with cats and beheading videos, among other things. One of the teenagers, Shamima Begum, had even communicated with an ISIS recruiter online before leaving for Syria.

Over the past two years, tech companies and governments have tried to counter ISIS's digital strategy, with limited success, so one group is trying something new. It's called Affinis Labs, and it's an incubator for startups, founded by Shahed Amanullah, a former senior adviser for technology at the State Department, and Quintan Wiktorowicz, a former senior director for community partnerships at the White House's National Security Council. Their mission is to pull together Muslim entrepreneurs to build social networking tools that help reduce the allure of ISIS.

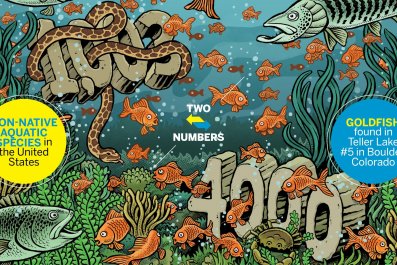

The incubator is currently working with eight businesses, including a Muslim dating site and a "Kickstarter for Muslims," to develop their ideas, get them off the ground and make them sustainable. The hope is to help Western Muslims find like-minded individuals instead of resorting to extremist groups for a sense of belonging. "All of these businesses peel away a tiny part of the problem," says Amanullah, "It may take a thousand businesses, which are a thousand different aspects of a person's identity, and collectively I think it can push back [ISIS]."

Extremism is one of the more immediate problems Affinis Labs is trying to combat. "Part of the reason [ISIS's campaign] is so effective is because it is organic. It's from the audience that it is going after," says Amanullah. "These young people understand youth frustration, they understand the fascination with violence, and they understand that the imagery and graphics that you see in Hollywood will attract these people."

To come up with new ideas, Affinis Labs holds hackathons all around the world, from Abu Dhabi to Australia. At each event, organizers pose a problem, such as how to make traditional Islamic scholarship relevant to the Twitter generation. Participants then have three to four days to come up with digital solutions. Affinis Labs provides money and assistance to support the best proposals.

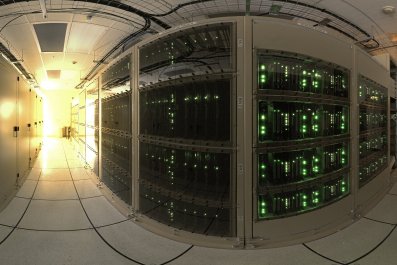

So far, the incubator is working on two ideas aimed at combating ISIS. The first is called One 2 One—an app to help identify people using extremist rhetoric and imagery on social media. The next step is for the app's creators to train a group of young Muslims (the ones who will download the app) on how to steer their peers away from extremism.

The second initiative is a website called "Come Back 2 Us." Its goal is to create a digital underground railroad for people who want to return home after joining ISIS. The site allows friends and family to post messages to those fighting abroad; the hope is that they'll trigger an emotional response and convince the recruits to leave. If the foreign fighters change their minds, they will be able to click a panic button and provide information that will then be sent to government contacts who can help them safely return.

The site is completely coded, but Affinis Labs has a few matters to resolve. The creators want to make sure ISIS and other groups don't target friends and families on the site. They also want guarantees from various governments that fighters who return after pressing the panic button won't automatically be locked up. Denmark is experimenting with rehabilitation programs for ISIS fighters who have decided to come home, while the Netherlands has either barred them from the country or forced them to wear tracking devices. The United States doesn't have a clear policy.

"We can't convince them to come back when they will just go to jail," says Amanullah. "And I don't think we need to consign them to death or lifetime in jail because they made a stupid mistake." If anything, groups of reformed fighters could be an asset, he argues—they could warn their peers about the dangers of joining radical groups.

While the founders of Affinis Labs view Westerners joining ISIS as an issue in and of itself, they also see it as symptomatic of a deeper problem: There are few well-known places online for young Western Muslims to meet and interact with people from similar backgrounds. "I think a big reason young Muslims are vulnerable [to recruitment]," Amanullah says, "is because no one is defining their identity for them.… On one side you have ISIS using these simple, slick messages, and on the other side you have clerics who stare into the camera and drone on for an hour. And one clearly resonates with young people, and one clearly doesn't."

Wajahat Ali knows this firsthand. The co-host of The Stream, a show on Al Jazeera America, used social media to kick-start his career and find a niche with a young Muslim audience, among other viewers. "The online space allows Muslim communities to bypass those institutions, both religious and cultural...that they feel do not represent them," he says. But without a dominant "Muslim Huffington Post" bringing Western Muslim diversity into the mainstream conversation, as Ali puts it, the community is often confronted with villainous or stereotypical portrayals of itself, which can be alienating.

"Having your identity and religion constantly investigated and interrogated would bog down any individual, isolate them, make them feel like 'this country will never accept me' and lead them towards this path of radicalization," he says. "But the overwhelming majority doesn't seek that out...or outright rejects it."

For now, both he and Amanullah say young Western Muslims in the post-9/11 world are still trying to find their place. And although the Internet isn't a panacea, it can be part of the solution. "We have a really talented group of people out there," says Amanullah. "I want to build a [Muslim online] community that has so much going for it, a person doesn't have to leave for some illusory utopia."