The number of migrants who perished in the early hours of last Sunday near the Italian island of Lampedusa in the Sicilian Channel may never be known. But then, precise figures on any aspect of the escalating European Union migration crisis have long proved impossible.

It is thought that the Italian Navy saved some 170,000 boat people in 2014 and brought them to Italy. It is also thought Italy's centre-Left government then lost all trace of 100,000 of them once inside Italy.

There have been persistent reports in Italy of police dumping coachloads of migrants at railway stations such as Milan and Rome in the hope that they will leave Italy.

No one should be surprised. Even if it were his intention, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi could never find space for all 170,000 – three times as many as the previous record in 2011 – let alone the 500,000 from Lybia alone expected to arrive this year. This figure is based on numbers of boat people so far this year, three times as high as in the same period in 2014.

There are a mere 66,000 beds in Italy's so-called "reception centres" (Centri di Accoglienza e Deportazione) scattered around the country, plus a further 13,000 places in temporary centres set up in disused government buildings and, increasingly, in hotels.

The only way for migrants to remain in Italy legally is to apply for political asylum, which means providing proof of name and country of origin. It takes at least six months to process these applications.

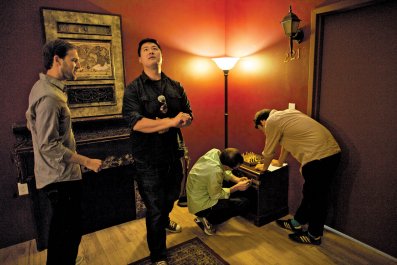

Everyone who isn't granted asylum is deported – in theory. But that is not what happens. Few of those handed deportation papers leave. They just disappear. And when those without papers refuse to tell the authorities their name and country of origin, Italy has no idea where to send them. Last year, approximately 40,000 deportation papers were issued but only some 5,000 migrants actually left Italy.

Migrants are allowed to stay in the reception centres for up to a year while their status is decided. Although surrounded by high security fences, these are not prisons and migrants are allowed out at certain times of day. They can also take courses in making ice cream and pizza – and in some cases learn to drive. It is easy to abscond for good whenever they choose and, in any event, they are allowed to leave once they have lodged an asylum request and been equipped with a document that gives them temporary permission to remain in Italy – though they are not allowed to work.

Fabrizio Gatti, a L'Espresso journalist who is an expert on the migrant issue, says: "Literally dozens of these foreigners are lost at all hours of the day and night. Rescued at sea and counted, once ashore they've just been left free to abscond." According to Andrea Maestri, a Ravenna-based asylum lawyer, the authorities actively collaborate in such absconding. "The police did this quite openly last year and no doubt they will do it again this year, too, in the summer when the wheel really flies off," says Maestri. "All you had to do was go to Milan station and watch the coaches pull up."

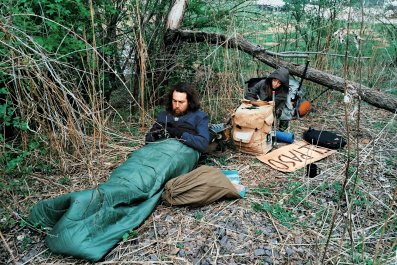

Many migrants do not want to apply for asylum in Italy, because the country's welfare system is virtually non-existent for people who have never had a job. Instead, they hope to move on to countries such as Britain and Germany where both work and welfare are easier to find.

It's easy to travel from Italy to France by train without passport or ticket checks. Many migrants camped out at Calais have confirmed they reached France via Libya and Italy.

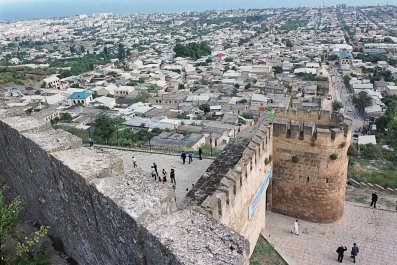

In the light of growing Italian anger at having to shoulder the lion's share of the burden of Europe's migrant crisis, the country's costly Mare Nostrum programme was replaced at the end of last year by Triton, an EU initiative, organised by its Border Agency, Frontex.

Italy launched Mare Nostrum after 366 migrants died in October 2013, when a single boat sank near the coast of Lampedusa. Its brief was to search for and rescue boat people right up to the Libyan coast and bring them to Italy.

This simply caused the numbers of migrants to escalate, according to critics, which included the EU Commission in Brussels and the British government.

Triton, on the other hand, is a European Union initiative whose brief is to police EU territorial waters across the Mediterranean.

The effect the change will have on migrant numbers and the number of deaths at sea remains to be seen. EU foreign ministers agree that the only long-term solution to the migrant crisis is to stop ships leaving from the coast of Africa in the first place.

But they also agree that, at present, this is unachievable.