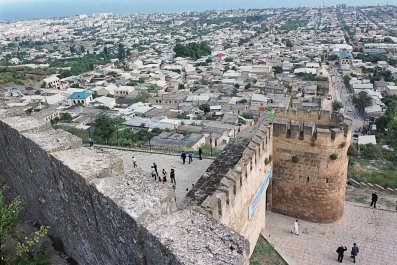

A century ago, on 24 April 1915, Ottoman authorities began to arrest hundreds of Armenian intellectuals. They were deported and most were later executed. The day is now commemorated worldwide as the start of the Armenian genocide, when hundreds of thousands – Armenians say 1.5 million – were driven into the desert to die or were murdered.

In Hungary, 16 April, Holocaust Remembrance Day, marks the start of the ghettoisation of Hungarian Jewry in 1944. Four hundred and thirty thousand Jews were deported from the ghettos to Auschwitz, where most were killed on arrival. On 17 April 1975, the Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, and began their programme of extermination.

The Bosnian war began on 5 April 1992, when Bosnian Serbs laid siege to the capital Sarajevo. Two years and a day later, on 6 April 1994, a plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down. The Rwandan genocide began that evening. In three months, Hutu extremists killed 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

"Twentieth-century genocides share striking similarities," says Khatchig Mouradian, co-ordinator of the Armenian Genocide Programme at Rutgers University. "The role of ideology, the use of propaganda, the methods used to annihilate differences and transfer assets to the dominant group, to name a few."

In Turkey the past remains hotly contested. Turkish officials strongly deny that a genocide took place. The Armenians, they say, were not slaughtered but deported because they sided with the Russians during the First World War. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the president, last year became the first Turkish leader to offer condolences to the Armenian community. But after Pope Francis referred to the deaths of the Armenians as "the first genocide of the 20th century", Turkey recalled its ambassador to the Vatican. A vote by the European Parliament to refer to the killings as "genocide" provoked similar fury.

Some argue that the Herero tribe suffered the first modern genocide. In 1904 some 65,000 Herero, in present-day Namibia, were slaughtered by German troops. The methodology was strikingly similar to that used in Armenia: the Herero were driven into the desert en masse and left to die. Survivors, and the mixed-race children of Herero rape victims, were studied by German scientists for their theories of eugenics. "The Nazis adopted the race research and experimentation that occurred in the Herero genocide," says Mouradian. "They looked at the late Ottoman empire's and early Turkish republic's methods of homogenisation and ethnic cleansing with profound admiration, learning much from it." A key lesson was the use of irregulars to carry out atrocities. Professor Taner Akcam, author of A Shameful Act, an authoritative study of the Armenian genocide, notes how Ottoman prisoners were released and then specially trained before being unleashed on Armenian civilians.

During the Holocaust the brutality of locally recruited auxiliaries in Nazi-occupied states shocked even the SS. For the Nazis, killing Jews was a military operation like any other. For their local allies, murder and humiliation was a pleasure, carried out with relish as they sought to prove their loyalty to the new racial order.

A similar pattern emerged in the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. Prisoners were released to form paramilitary groups which carried out many of the worst atrocities. The paramilitaries operated under a separate chain of command, reporting to the Ministry of Interior. "Hardened criminals were freed. They had to do some nasty stuff, but they could feel patriotic," says Tim Judah, author of The Serbs. "They could expunge their criminal past, get a free pass for looting and feel they were doing something good for the nation."

In Rwanda members of the Interahamwe, a Hutu paramilitary force, carried out the killings with clubs and machetes. The Shabiha militia, a former smuggling organisation, has been blamed for some of Syria's worst atrocities. It was set up with state support but operates at arms' length.

A line of blood runs through modern history: from the deserts of Namibia and Syria to Auschwitz, Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and now back to Syria. "The perpetrators," says Mouradian, "repeat history precisely because they have learnt from the past."