With his beautifully coiffed hair and gunslinger bravado, Rick Perry was once considered a strong contender for the 2016 Republican nomination. But these days, Perry, despite having improved his campaign style since 2012, has fallen off just about everyone's short list for president. So earlier this month, at an event in New Hampshire, he seemed peeved as he made the case for his candidacy. Having spent 14 years as governor of Texas, the 65-year-old chose to emphasize the biggest notch on his cowboy belt: experience. Taking thinly veiled shots at some of his younger rivals, Perry asked reporters, "Do you want to take a chance on someone who doesn't have an executive track record of being an executive?"

An Air Force veteran, Perry then went into this-is-your-pilot mode. "If you're flying from Boston to London, [do] you want to be flying with somebody who gives a heck of a good presentation on aerodynamics and why the airplane stays in the air, that has you on the edge of your seat with excitement because they're such a great speaker...but they got 150 hours of flying time?" Perry asked. "Or do you want to be with that grizzled, old, 20,000-hour captain who's taken that airplane back and forth thousands of times safely?"

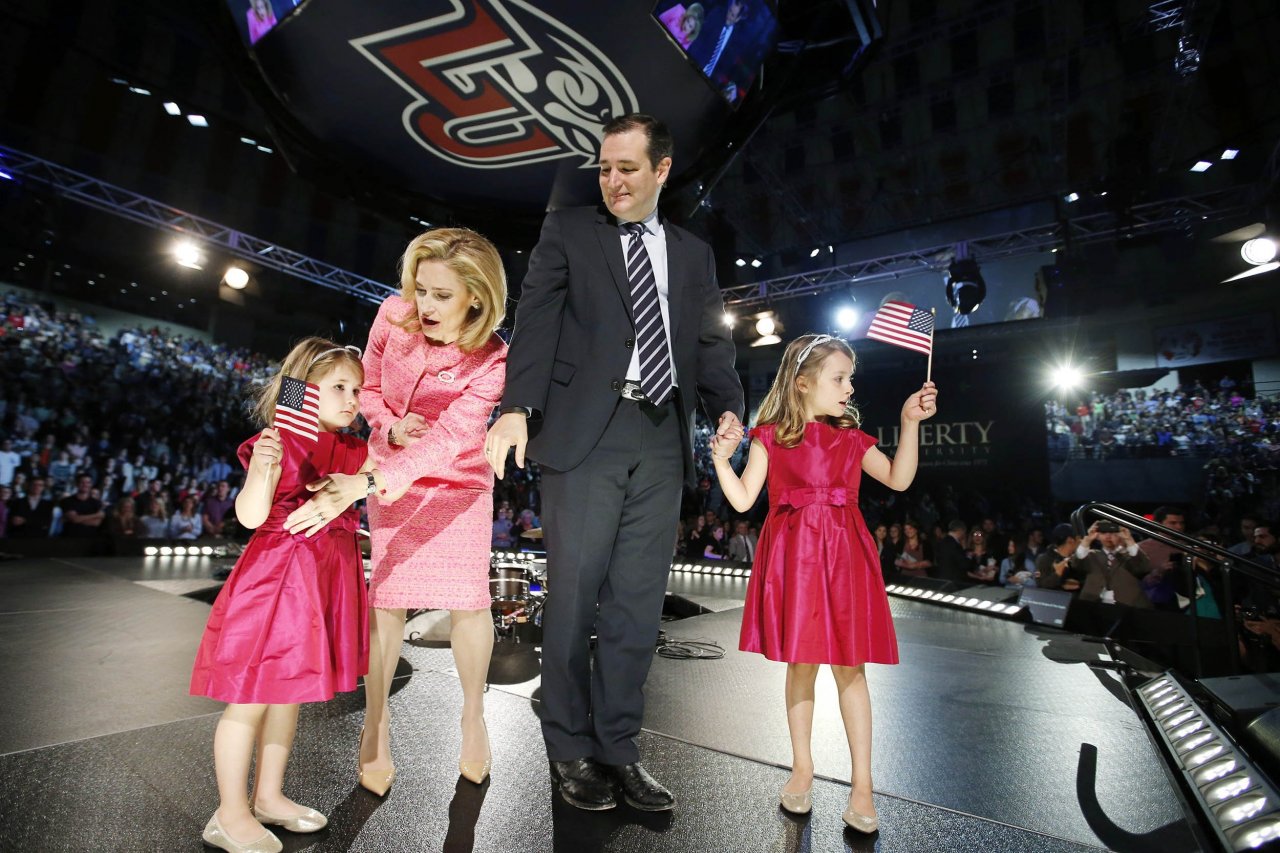

Even when they're grasping for zippy metaphors, few presidential candidates boast about being "old" or "grizzled." But when it comes to experience, the candidates work with what they've got. What's frustrating for Perry and some other seasoned politicians is the ascendance of three upstart, freshman senators—Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio and Rand Paul. All are running as party renegades, and all have a plausible path to the nomination.

With few exceptions, such as Bobby Kennedy in 1968, freshman senators tend to wait their turn before making a serious run for the White House. Lyndon Johnson spent 23 years making backroom deals in Congress before his brief, failed bid at the convention in 1960. Bob Dole logged 18 years in Congress before making a short-lived bid in 1980 and wasn't a serious contender until 1988. So why are we seeing so many first-term senators jumping into the race? Blame Barack Obama, who in 2008 leapfrogged his way to the Oval Office. At the time, Obama, a 47-year-old first-term senator, defined the experience gap. Compare his résumé to that of Joe Biden, who, for 16 years, idled in Congress before making his first presidential bid, in 1988.

Another major factor: the Tea Party. Since its emergence amid the economic wreckage of 2009, the right-leaning group has grown in numbers and influence, propelled by the belief that the Washington establishment is unfit to govern. Ever since, the fickle American public has been waffling between the feeling that all politicians suck and a desire to elect someone with a proven track record. "At one time, a Ted Cruz couldn't get the money or the party would keep him in check," says Samuel Popkin, a political scientist and former campaign consultant. This year, Popkin adds, "experience can tarnish," a candidate. Which means few in either party want to spend decades sitting in all those yawn-inducing subcommittee hearings.

BETTING ON A BEGINNER

Part of the reason American voters have been vacillating over experience in recent years is the nature of presidential politics. We're not a parliamentary system in which seasoned party leaders wait for their chance to become prime minister. Every candidate is free to define who they are, separate from their party. Sometimes the results are amusing. Post-Watergate, former Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter highlighted his outsider status but also tried to bolster his experience creds, claiming he governed "the largest state east of the Mississippi." (By that square-mile standard, we should elect Sarah Palin. Or any other Alaskan politician.)

This year, the leading candidates are Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton. Both have plenty of experience, but because of their ties to past presidents, and the baggage that comes with it, both have to find a way to tout their accomplishments without seeming as if they're from the Pleistocene era. In her introductory 2016 campaign video, released in April, Clinton made no mention of her career highlights and no reference to her experience as first lady, senator or secretary of state. Rubio, in his announcement speech, dubbed Clinton a candidate of "yesterday," and his call for generational change was widely seen as a dig against Bush.

In previous decades, the bar for experience tended to be much higher, as the public held politicians in higher esteem. Richard Nixon ran on experience in 1960, but his young opponent, John F. Kennedy, had spent 14 years in Congress—more than Cruz, Paul and Rubio combined. Candidates with no previous electoral experience, such as Herbert Hoover and Dwight Eisenhower, had achieved national fame for leading disaster-relief efforts and helping to win a world war, respectively. Woodrow Wilson's electoral experience consisted of just two years as governor of New Jersey, so he was the exception.

In general, voters put more weight on experience in good times and less weight on it in bad ones. In 2008, the Pew Research Center asked voters what word came to mind when they heard the name "Barack Obama." "Inexperienced" was the most common response. That should have been problematic for the young politician. But because of the economy's free fall, voters decided to gamble on a relative neophyte.

As Obama approaches the end of his second term, the economy has improved. But the barrier for entry is still low, especially on the Republican side, where the Tea Party anti-incumbent ethos is strong. Five years ago, Paul was an ophthalmologist in Kentucky. Cruz and Rubio had experience on the state level, but nothing approaching Obama's national profile. Both wound up knocking off favored, establishment candidates in their Republican primaries, then easily winning in the fall. It helped that the Tea Party frowned on Washington lifers and lauded citizen legislators. The lesson politicians took from the experience: Waiting is for suckers. With an electoral tableau of voters still feeling insecure, the newbies have a lot going for them.

BALLS OVER BILLS

The rise of these rookies is clearly frustrating to Washington stalwarts. Case in point: Rick Santorum, the former Republican senator from Pennsylvania. In the 1990s, Santorum was young man in a hurry, much like Rubio today. But compared with the three freshman candidates, Santorum is Daniel Webster, not because he's ancient—he's only five years older than Paul—but because he sees the Senate as a place where you work your way up and try to pass legislation. Asked about the freshmen senators making presidential bids, Santorum told Newsweek that being president shouldn't require "on the job training."

Unlike their predecessors, the three freshmen aren't running on their lack of experience, nor are they trying to inflate their congressional records. As the 2016 election approaches, the notion that "I-passed-HR 2134" seems increasingly quaint. Voters don't seem to care about bills, and in the scrum of Republican primaries, where an instigator can count on as much funding as a legislator, there's no benefit to relying on your record.

For Cruz, who two years ago stymied the Senate with a hopeless Obamacare filibuster, what makes him qualified is less about passing bills than about having the cojones to stand up to Congress, even if his principled stance was both costly and doomed. A self-styled "courageous conservative," he told Fox News that the best thing he's done in the Senate is "stopping bad things from happening." On the other hand, Rubio, a former state legislator, has been a more traditional senator. Paul has built some interesting coalitions across party lines. But all three are running as insurgents, not lawmakers.

Political scientists have long argued about what kind of experience makes a good president. They've looked at time in office as a predictor of success and haven't found much of a relationship. The venerable Abraham Lincoln had just one term in the House of Representatives. Richard Nixon's bloated résumé included the House, the Senate and the vice presidency, and he wound up turning the Oval Office into a criminal enterprise. Business experience doesn't seem to be a good indicator of a president's economic success. Look at agri-businessman Jimmy Carter or mining executive Herbert Hoover.

Which is why Perry's argument about experience—and Cruz's emphasis on his lack thereof—is perhaps less relevant than voters tend to think. As John F. Kennedy once put it, "There are no guarantees that if you take one road or another that you will be a successful president."