Kurt Vonnegut never warned me to wear sunscreen, but he did speak at my college graduation. He also had a house a town or two away from where I grew up. And one time in New York City, I spent hours talking to a girl I had met at a bar about Cat's Cradle. I wound up marrying her, and at our wedding, instead of Corinthians or one of the typical passages, we had an old friend read an excerpt from Vonnegut's Mother Night. So you could call me a fan.

You could even call me part of Vonnegut's karass. Coined by the author, it's a group of people linked in a cosmically significant manner, even if the connection isn't immediately apparent. Like when you wind up marrying someone you just ran into one night. Or when you write a letter to a famous author and spend the next 30 years trying to make a movie about him.

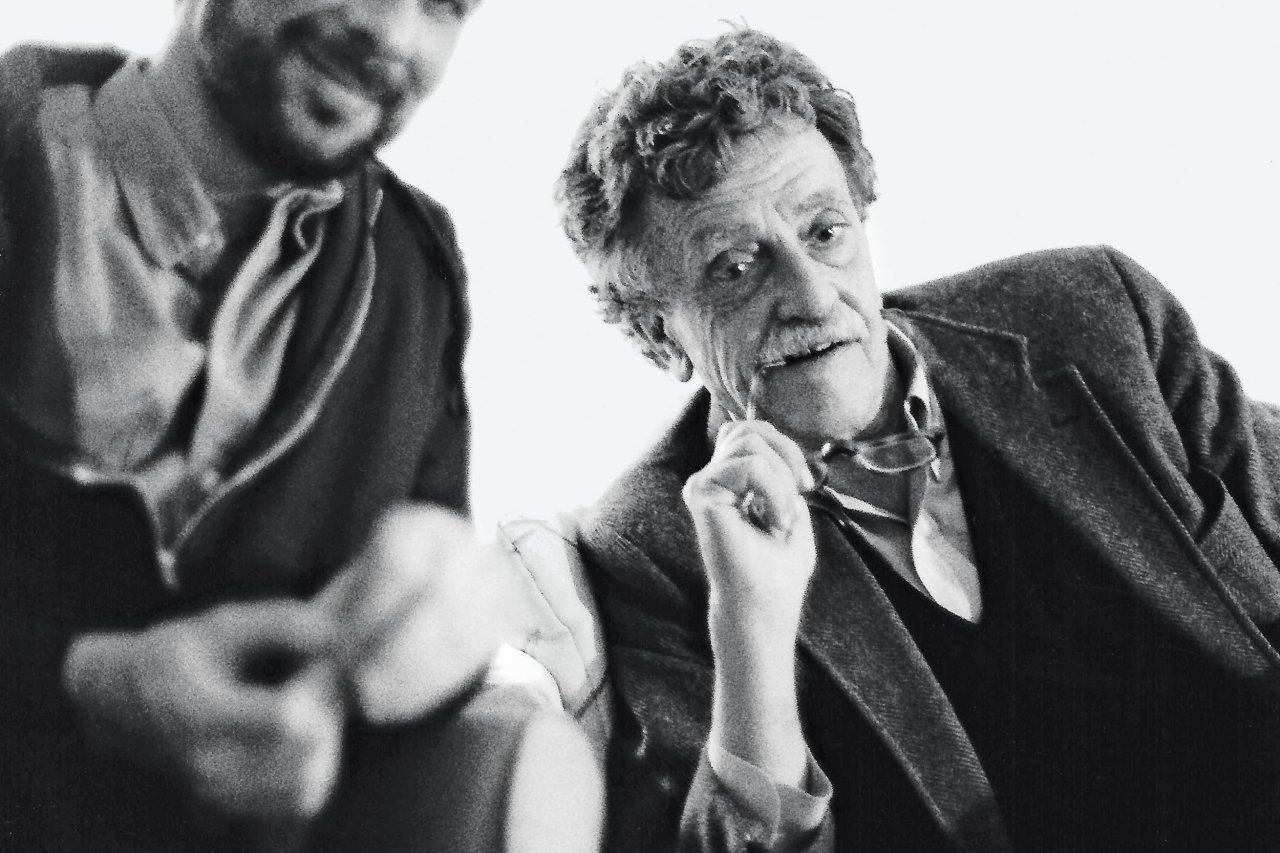

This last example is what happened to Robert Weide, an executive producer of Curb Your Enthusiasm who has directed and/or produced documentaries on the Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields, Lenny Bruce, Woody Allen and now—thanks to a Kickstarter campaign—Kurt Vonnegut.

Here's what happened: In 1982, after completing The Marx Brothers in a Nutshell for PBS, Weide wrote to Vonnegut. A big Marx Brothers fan himself, Vonnegut had seen the film and wrote Weide a friendly response. "He basically said, 'I'm an author. How you make a film about me I don't know, but you're welcome to try. Here's my phone number in New York,'" says Weide. "So that was quite a letter to get from my literary idol."

Weide soon flew to New York to meet his subject. "The great irony is in that initial letter I say that I'm sure I can arrange for financing immediately," says Weide. That was July 1982. "I thought it'd be a snap and I'd have a film ready [the] next year. Boy, it sure didn't turn out that way."

PBS gave Weide the seed money to do his first filming in 1988, with the idea that it would be an American Masters episode. But neither PBS nor Weide could come up with enough money to finish the project. "It just lingered, and I figured, I'll go out of pocket. I want to keep filming him. So I did, over the years, always figuring at some point I'd find the money."

Weide later got turned down for a grant that would have been enough money to complete the film. "They didn't take him seriously as an author," Weide says. "He falls into this weird midrange in that lowbrows consider him an intellectual, and intellectuals consider him a populist author, or too lowbrow."

Eventually, he was persuaded to turn to Kickstarter - despite being convinced that only celebrities could get their projects funded on the crowdsourcing site. Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time met its funding goal in mid-March, and Weide hopes to have the final film ready by the end of the year.

The documentary will go a long way toward filling out Vonnegut's "greatest generation" origin story, which is told by the man himself in footage shot during a trip to his childhood home in Indianapolis. Some of these scenes were even educational to Vonnegut's daughter, Nanette. "My father invited me to Indianapolis, and he didn't say anything about a documentary being filmed. I was kind of grumpy that I had to share my father with a camera crew," she says, "[But] it was pretty wonderful and intense for me.… He was in a zone…. And remembering his childhood very fondly, of course, before the war, before things got really dicey."

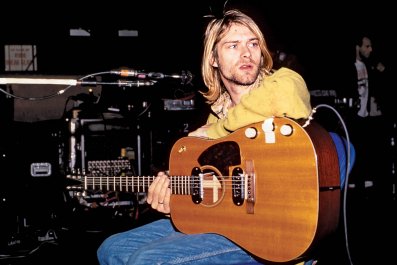

Vonnegut's experience in World War II is well-documented: He fought in the Battle of the Bulge, then was taken prisoner by the Germans and held in Dresden, where he witnessed the firebombing of the city by the Allies and was one of a handful of people to survive thanks to the dumb luck of being stashed underground in a meat locker. Witnessing what war does to people provided the raw material for Slaughterhouse-Five.

Initially, Vonnegut published novels that more often than not went unreviewed, paperbacks that were sold on revolving racks in drug stores and bus depots for 35 cents a pop. ("A remarkable and terrifying novel of how life might be for the space travelers of the future" warns the jacket copy on the lurid cover for the original edition of The Sirens of Titan.) The books didn't sell—at least not until the 1969 release of Slaughterhouse-Five, which made him world famous at the age of 47. That book's been blessed and burned, ballyhooed and banned.

A major theme in Vonnegut's work is the nature and passage of time, and because of Weide's funding problems, it's also a big theme in the film. "Unstuck in time" is a reference to Slaughterhouse-Five—thanks to a sort of time-traveling post-traumatic stress disorder, main character Billy Pilgrim experiences moments from his life in a nonlinear fashion. And so it goes with Weide, who started this project at age 22, when Vonnegut—whom he affectionately refers to as "the old man"—had just turned 60. "This year, I'll be four years short of the old man's age when I met him. And I'm still working on the same damn film! It's just crazy."

Jerome Klinkowitz, one of the first academic critics to seriously evaluate Vonnegut, sums up the author's appeal. "He sounds like an American, and he sounds like an American who you can trust...the same way that Mark Twain still sounds like an American...and we trust him."

And Vonnegut trusted Weide, who recalls that, "Whenever I'd say, 'If you're going to Indianapolis, why don't I go with you? We'll drive out together, and I'll do some filming there.' He was always up for that." But after decades went by without a backer, the film became a running joke between the two men, "It was 'the film that wouldn't die' or 'that wouldn't live,'" says Weide. "I was always filming him. But by that time, we were getting together just because were friends, with or without the film."

The eventual blurring of their personal and professional relationship led Weide to bring in filmmaker Don Argott (Rock School), as he felt he could no longer be objective about the dozens of hours of footage he shot from the '80s until Vonnegut's death in 2007. "[Weide] is like family," says Nanette. "What I feel with this documentary is just a depth of material that is staggering. He's got it exactly right. It just takes my breath away."

Vonnegut got to see some footage before he died, "so he knew that there was actually film in the cameras," says Weide. "We did have a screening of the rough-cut.... I sat next to him and heard his little reactions to the film, and a lot of things really touched him and made him wipe his eyes. So I had the pleasure of knowing that he saw this in some form."

Vonnegut remains as relevant as ever, even eight years after his death, largely because he understood the absurdity of humanity. What once seemed like very speculative fiction now seems like reportage. "I think he understood that the world was going to hell, so it all came down to what you did individually," says Weide. "He talks about saints. And to him, a saint is somebody who makes other people's lives easier in not just big ways but small ways. A smile or a thank-you or whatever."

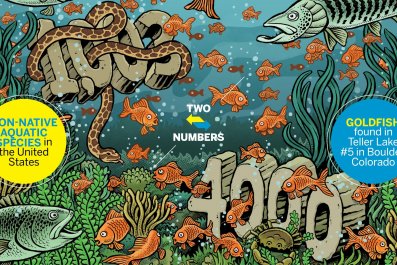

Like the 3,755 Kickstarter backers of Unstuck in Time, a karass to whom all Vonnegut fans owe a smile.