The Apple Watch's constant notifications are to concentration what a Cinnabon is to fitness. As popular reviewer Joanna Stern found out while field-testing an Apple Watch, the thing can leave you more distracted than a beagle in a squirrel sanctuary.

Early buyers are just beginning to strap on Apple's newest gadget, but ultimately this gizmo and its descendants will have an impact on society that goes far beyond our wrists: The Apple Watch will shrink attention spans like nothing before.

Holding people's attention in a busy media landscape is an old problem—Al Ries and Jack Trout called it out in their famous book Positioning in 1976. TV seemed hyper compared with print; the Internet felt like chaos to the TV generation; and now some of our big thinkers mince their brainy theses down to tweetstorms for cellphone screens. Some research shows that our average attention span has dropped from 12 seconds in 2000 to eight seconds today. While the intensity of bombardment is already crazy, smartwatches are going to take this to the next level of demand for our attention, since they will be on your body, all the time.

The chief trait of this new tool is that it shrinks your digital activities down into short bursts. Apple's watch puts these notifications in front of you either by flashing something on its face or vibrating on your skin. Interactions with the watch are expected to take no more than eight seconds—quick glances at calendar items or yes/no answers to texted questions. Depending on what you opt into, the watch could relentlessly interrupt whatever else is going on inside your head or in your life.

Such short attention spurts are not intrinsically bad, unless you're a grandfather who wants to grump that when you were a kid a night's entertainment consisted of reading the entirety of Atlas Shrugged by flashlight. And anyway, the trend is not going away. Complain as you may, but the bottom line is: Get used to it.

For the next year or so, the pricey and still-clunky Apple Watch will be conspicuously worn by the same types who a couple of years ago got labeled "Glassholes" for peering through their Google Glass lenses. But in time, as the technology evolves and prices drop, some version of a smartwatch will become a significant new tool that infiltrates our lives.

Evernote CEO Phil Libin argues that spasmodic interactions with the Apple Watch will actually be more in tune with how our brains work naturally. "Our ancestors weren't working on a document for six hours," he tells me. Instead, ancient humans' attention constantly flitted between finding something to eat and checking to see if something was about to eat them. Libin believes we'll be more productive if we can handle simple tasks in seconds on a watch. And he may be on to something: Studies show that people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are more creative. Other research, even going back to some Buddhist writings, says five to eight seconds is about the amount of time your brain can hold on to one particular thought.

Of course, somebody at some point has to concentrate long enough to design a skyscraper or write complex code—though even there, the trend is toward dividing big tasks into smaller ones and throwing them to Agile development teams. Fading are the days of attacking a major project like a great white shark hitting a seal. Now the approach has more in common with a school of piranha.

In both business and everyday life, we're about to see the most intensive demand ever on a limited supply of human attention.

The supply of attention can't keep up. Every human has only 24 hours of possible attention, give or take sleep, and YouTube uploads 300 hours of video every minute. As demand for our eyeballs spikes, the value of the supply goes through the roof. If you could buy stock in attention right now, it would be the best investment since Berkshire Hathaway in 1965.

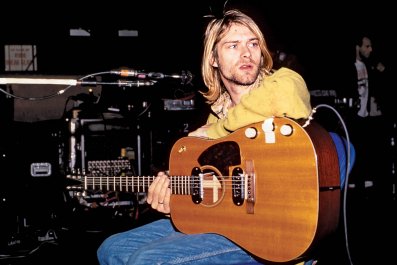

Anything that's really good at getting and holding our attention will become far more sought after—and far more valuable. Take, for instance, the Coachella music festival, which just sold around $80 million worth of tickets for two weekend performance sets in April. It is a veritable magnet for the mind, holding the attention of 100,000 attendees for three days at a time. The amount of attention Coachella controls is so valuable, nearly every band and brand is dying to be a part of it. "It almost matters too much," Flying Lotus, a producer and DJ, told The New York Times. "This is one of those festivals where the whole world is watching."

In the age of the smartwatch, Coachella's rare ability to attract attention will become even more remarkable—and more valuable to any entity that wants to make a deep impression. The same will apply to similar events, such as Bonaroo, and major sports events, both live and on television. Or how about Costco? No one can escape a Costco in less than an hour. Its ability to capture so much sustained suburban attention becomes a mega-asset in an age when so many digital retailers have to compete to get you to buy in eight seconds or less.

In a similar way, the value of face-to-face meetings will only rocket. It won't matter how good Skype and Google Hangouts get for video conversations. Meeting live is a serious investment of time and focus, and it will make more of an impression in this new age than it did in any old one.

An interesting question, though: What will a hyperactive smartwatch do to the live meeting? Laptops can stay in bags and phones can stay in pockets, but watches will be right out there on wrists. As early reviewers have found, glancing at a smartwatch is not a deft and unnoticed gesture. In fact, looking at a watch, even just to tell the time, sends a signal of boredom or agita. George W. Bush took a quick look at his watch during the 1992 presidential debate against Bill Clinton, and some say it cost him the election. It might become a sign of deep respect to show up to a lunch date with nothing on your wrist.