Wherever you are in the world you are unlikely to be that far from an art fair, biennale or local branch of your favourite super gallery. There are, however, certain lodestars,

the most effulgent of which is ArtBasel. For a week or so in June the Rhine-side city becomes art's epicentre.

The best art in Basel, however, is not necessarily seen during the frenzied few days of the fair but at other times of the year, as when I went in late March to the Fondation Beyeler to see the Gauguin show.

It is a brilliant, subtly curated exhibition, beginning with a self-portrait of the artist in weird Symbolist fancy dress and ending with another self-portrait executed in the year of his death, an old, syphilis-weathered face peering through small John Lennon spectacles, the showmanship and flamboyance of his younger years stripped away.

Gauguin's life is so huge that it does not obscure his art, but becomes it. As a child, Gauguin lived for some years in Peru. As a teenager he enrolled in the merchant navy. Later he seems to have enjoyed some success as a financier, enough at least to start collecting Impressionist paintings before deciding to become an artist himself. His life thereafter became picaresque: he travelled the world from the polar regions to Polynesia, worked with Van Gogh and made friends with (and on occasion fell out with) pretty much all the cultural leaders of the day, from Strindberg to Pissarro.

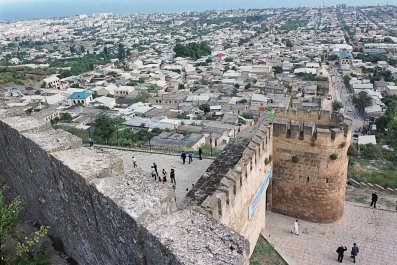

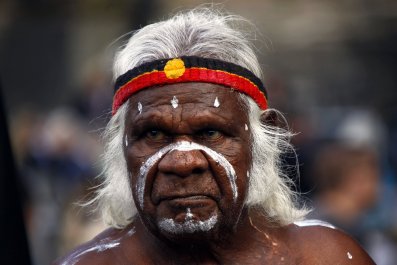

He seems to have spent his life looking for something that he never found. There is an almost Jungian aspect to his quest for a mystical universal human experience, which he thought he would discover among the primitive peoples of the South Pacific. Upon arrival, however, he found European colonialism had got there before him. The "purity" of a world uncontaminated by European notions of progress would remain tantalisingly just beyond his reach; yet in the works on show here it is almost possible to see him trying to paint this elusive idyll into existence.

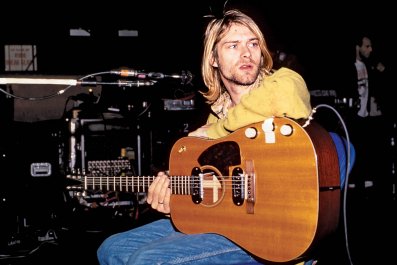

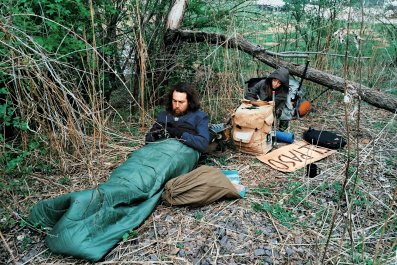

Part of Gauguin's stock-in-trade was his racketiness, which fed into the image of the rebellious, dissolute loner, something of a proto-hippy. There are frankly unappealing aspects of his character – viewed by today's standards, he would probably be prosecuted as a sex tourist preying on minors. He gorged himself on the exoticism of these ever more extreme environments, soaking his art in the colours and strangeness of his surroundings – and his capacity to shock was part of his commercial value.

The show dwells at length on the Polynesian paintings, of which the most remarkable is D'ou Venons nous? Que Sommes Nous? Ou Allons Nous? It does not answer any of those questions but it is a remarkable thing to look at, a giant work that transcends its depiction of the exotic. After its completion and believing it to be his best work, Gauguin attempted to take his own life by ingesting arsenic; he survived but his health never recovered.

It must have taken some persuading to get Boston's Museum of Fine Arts to send it. Not just Boston, there are loans from the Musée d'Orsay, the Pushkin, the Hermitage, Moma, the Thyssen and many others. No wonder the show took six years to put together. It is called the foundation's most involved project, but then the Museum's director, Sam Keller, has form in dazzling coups. Before running the Beyeler, he was ringmaster of the ArtBasel circus and, as the man who expanded the fair to Miami, is one of the leading art impresarios of our age; a reputation that this show will only burnish.