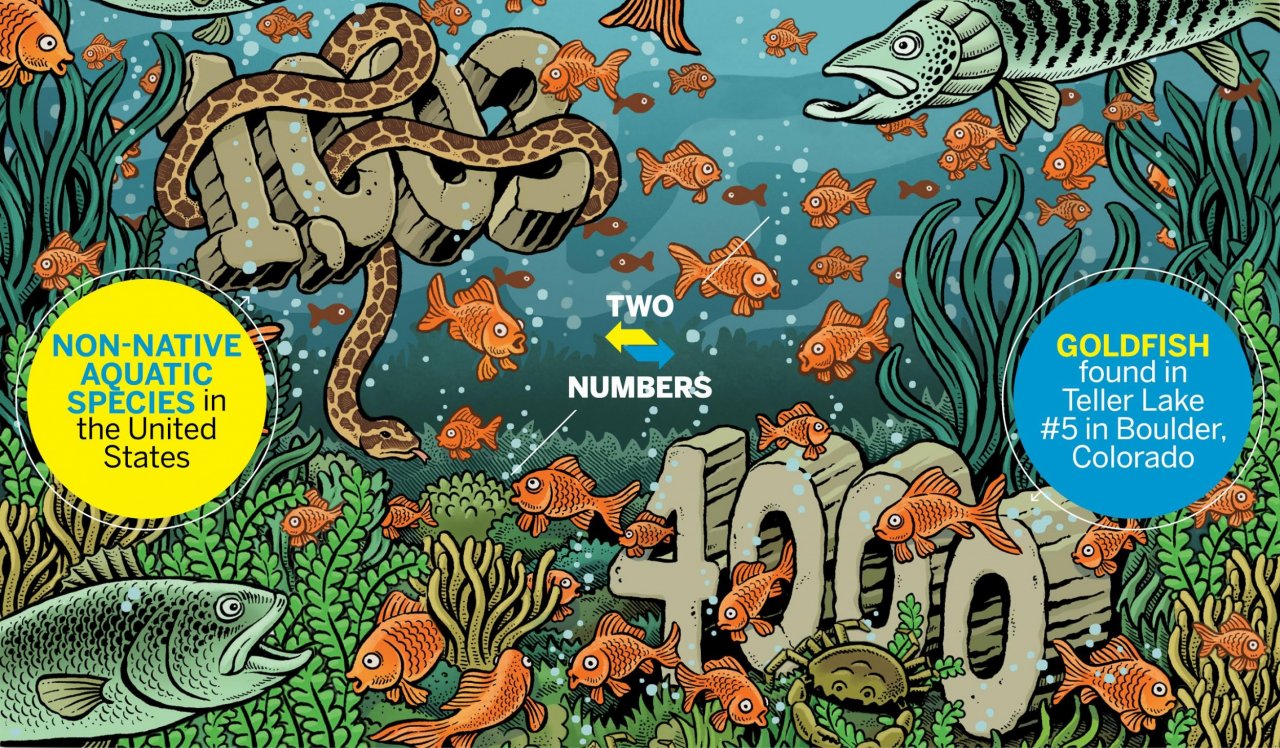

"Someone just didn't want their goldfish anymore. We don't think there was malice intended, but now we have 4,000 goldfish. And that's an issue," says Jennifer Churchill, public information officer for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, adding that Teller Lake No. 5, a 12-acre expanse of water near Boulder, was overrun with the county fair critters.

Aquarium dumping has led to several exotic aquatic species being introduced to ecosystems in which they don't belong—perhaps most notably the Burmese python in Florida's Everglades.

The United States Geological Survey has reported that 1,003 non-native aquatic species have been introduced into various bodies of water across the country. (Some of these species may have been eradicated, though it would be impossible to check every body of water to confirm, said Matt Cannister, a fish biologist.) Of that total, 688 are fish, with frogs, turtles, snakes, shrimp, crabs and mussels filling out the list.

It's not clear exactly how many of those 1,003 non-native species are considered invasive—defined by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) as species that harm the local economy or human health. The agency says it lacks the resources for such detailed research. Some known invasive species are zebra mussels, which can clog pipes and cost millions of dollars to remove, and European green crabs, which both outcompete New England soft-shell clams and prey on them. The soft-shells, a highly valuable seafood product, have withered as the green crabs have thrived.

Goldfish aren't wreaking havoc on human health or finances (yet)—but they are throwing off the delicate balance of an ecosystem. "Any species that ends up in an ecosystem in which it did not evolve, it doesn't have all the checks and balances that affect the creatures who occur there naturally," said Don Maclean, an FWS biologist. "This non-native animal, like a goldfish, might not get preyed on as much; diseases and parasites don't bother it as much. These are all qualities that help them reproduce faster and better. When that happens, the non-native species is eating more while the native species are struggling for food."

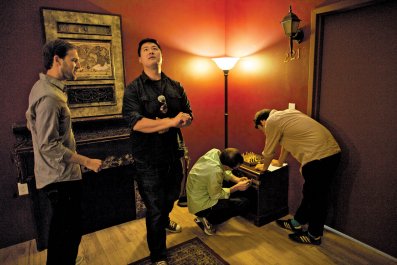

To rid Teller Lake No. 5 of the goldfish, Colorado Parks and Wildlife authorities are considering electrofishing, basically zapping all of the fish with a jolt of electricity. The stunned fish float to the surface and can be removed.

Churchill has received dozens of calls from locals asking if they can take the goldfish home as pets, but she believes that would set a bad precedent. Instead, Colorado Parks and Wildlife will donate the goldfish to a bird of prey rehabilitation center, where they will be eaten.