We're inventing the post-Mom economy, which—not to insult mothers or anything—should make us all happier and richer and finally bring us the leisurely future we were promised 50 years ago.

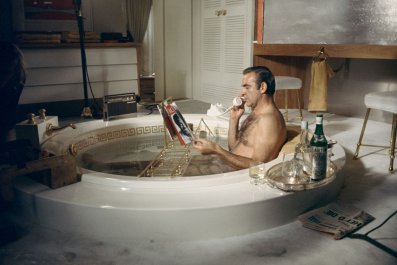

Give it another decade and we might not have anything to do outside of work except exercise at the gym or drink 3-D-printed bourbon at virtual-reality Star Wars bars.

At its core, the post-Mom economy means nobody will have to do his or her chores and everybody can do other people's chores. Platforms like TaskRabbit create a market matching odd jobs to job-doers. Early post-Mom companies include Washio, which helps you get your laundry done, and Dufl, which gets someone to pack your suitcase for you. Trunk Club is kind of a Garanimals for men—it helps fashion oafs pick out what to wear. These companies have all gotten tens of millions of dollars in venture investment.

Coder Aziz Shamim captured the basic ethos of the post-Mom economy in a much-retweeted tweet earlier this year: "OH: SF tech culture is focused on solving one problem: What is my mother no longer doing for me?" ("OH" is "overheard" in Tweetish.)

His comment was taken by many as an indictment of tech culture. We have big problems—global warming, poverty, runaway obesity—yet 20-something entrepreneurs expend their considerable talents on starting companies that mainly serve bratty 20-somethings with too much money. These entrepreneurs get advised to solve a problem in their own lives, and that problem often seems to be not having a parent nearby anymore.

But look at this through the long lens of labor-saving inventions. In the 1950s and 1960s, electricity and mechanization met up with a postwar booming economy, and we started concocting a new future of freedom from drudge work. This is when the masses adopted clothes-washing machines, dishwashers, vacuum cleaners, power tools, microwave ovens and powered lawn mowers. Chores done by hand for generations, like scrubbing laundry in a washtub, suddenly disappeared from average, everyday life.

And the trajectory itself was exciting back then. If so much could become mechanized so fast, surely it wouldn't stop. The Jetsons cartoons of the 1960s featured Rosie the house-cleaner robot. Rosie was a little bit sci-fi and a little bit what we expected to get soon.

But the technology hit a wall. Mechanization couldn't be made to clean the bathroom, fold clothes or run errands. In the past 50 years, what new inventions have automated our crappy chores? Maybe the Roomba vacuum and automated cat litter boxes, but not much else. We haven't even gotten a mass-market, GPS-guided robot lawn mower, which you'd think would be a no-brainer by now.

Well, today, connectivity and software are bringing us a Rosie work-around. Instead of building machines to do chores, we're creating a giant system that efficiently lets all us humans do one another's chores. That's more brilliant than it might sound, because now everybody can do the chores they do well and efficiently, and slough off the chores they hate or suck at.

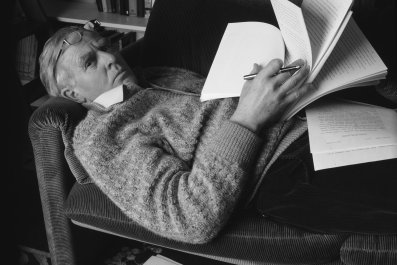

There's a widely accepted economic formulation that tells us why such a chore exchange should help lift all of our fortunes. It's called comparative advantage, attributed to 19th-century economist David Ricardo. He applied it to nations and free trade. The theory says that if countries do what they are "most best" at and then trade their most-best products and services for other countries' most-best products or services, all the countries involved increase productivity and get higher-quality stuff at falling prices. In other words, when every country focuses on what it does best and trades, quality of life improves for all.

Over the past few decades, companies have also embraced comparative advantage, increasingly focusing on core competencies and outsourcing everything else—usually a winning strategy. Today, the Internet, mobile phones and software platforms for the first time make "most-best" trading efficient and easy for individuals. So now we little people can apply Ricardo's theory too.

The founders of post-Mom companies might think they're just saving themselves from toil, but they're actually giving us all ways to do our most-bests and farm out the rest to others who can do their most-bests. On the flip side, these systems let any of us make money off our most-bests, which can then help pay for all the most-best services we buy. It's a big circle that, if Ricardo was right, makes all our lives better.

Some deride the post-Mom companies as a fad, but that's probably wrong. In the U.S., where most of the post-Mom companies get started, people in their 20s are a demographic bulge. That helps the post-Mom companies find a fertile market and get traction in a big population of singles who recently left home. In a decade, that group will be largely married, with kids and a mortgage and a whole different set of priorities. Does that mean they'll likely give up conveniences like Washio?

Lord no! Look at the baby boomers who grew up with dishwashers. Try selling them a house without one. When a generation comes of age with a new convenience, you can bet they're going to demand that convenience for the rest of their lives. They're not going to go back to cooking every night instead of ordering from Seamless or Blue Apron, or styling their own hair instead of finding assistance through the Madison Reed app.

In fact, the post-Mom trend is only beginning, but it could take a different turn in coming generations, a turn that could disrupt today's startups. Artificial intelligence seems likely to become the basis for post-Mom services that cut out humans: driverless cars that shuttle around our kids, or AI tutors, or piano teachers. Weirdly, a Rosie-like robot now seems within reach, powered by AI that lets it learn to do household tasks.

At that point, it will be only a matter of time before technology delivers the ultimate post-Mom invention: the robot Mom. Then we'll have come full circle. The robot Mom will never tire of telling us to do our chores.